Publication

Walking Together

A Practical Guide for Strengthening Partnerships Between Schools, Families, and Communities

Imagine this: A community comes together to set a vision for its public schools.

In local libraries, neighborhood associations, school cafeterias, and places of worship, families sit down together and share their hopes and dreams for their children. They think about what schools need to do to better equip students for college, career, entrepreneurship, and service to their communities. They talk about the need for more teachers who reflect their demographics, and translation resources that help family members communicate with teachers and school staff. They contemplate improving access to sports and arts programs. They imagine more college counselors and challenging courses that help students enter college prepared for success.

Together they talk about what they love about their schools and what they’re worried about. They articulate their long-term vision for success—not just for their school or school system, but also for their young people.

Then, imagine that same community is also involved in the hiring process for a new superintendent or principal. They help ensure that district and school leadership understand their vision and pledge to work alongside them to make it a reality.

They ask: What strategies will you use to help us get our schools to where we want them to be? How will you work alongside us? How will we know that our voice is heard in this district and that our schools represent our community? Together they craft a strategic plan that takes advantage of the community’s unique strengths. That is real, authentic community engagement.

That is real, authentic community engagement.

We know it’s possible, because it is happening in pockets across the country. Now it’s time for all schools, districts, and charter networks to take on this work.

In Walking Together, we’ve gathered together some of the best thinking and most challenging questions from Durham, North Carolina, Brevard, Florida, and elsewhere.

Click through, check them out, and tell us what you think: Where have you seen or experienced authentic partnerships between schools, families, and communities? What have you learned? What should we know?

Table of Contents

The Case for Community Engagement

Districts: On the Road With Dr. Blackburn

Schools: Language Isn’t a Barrier

Families: A Parent’s Bill of Rights

The Case for Community Engagement

In education, we’re lucky, because we already have a strong foundation on which to build our work—the people who make up our communities. They’re our constant, even as superintendents change (on average every three years), school boards turn over (every five, on average), and teachers and principals move on. When communities work alongside districts and schools as full partners in student success, true change is possible. Research shows authentic community engagement leads to improved academic outcomes for students, combats absenteeism, and increases enrollment.

If you were building a house, you wouldn’t neglect the foundation; you wouldn’t install the windows or the doors without it. Unfortunately, folks who work in education too often neglect the foundation. We think of families and community members as passive bystanders instead of active participants in their children’s education—benefiting from our expertise, rather than experts in their own right.

Even when districts or individual schools make efforts to engage with the communities they serve, those efforts are often insufficient or misguided. Traditionally, “community engagement” has meant giving information to families—a one-way process—or asking for one-off feedback. This may be well-intentioned, but it fails to achieve the level of shared decision-making and ownership that can have a transformative effect on a school community. Even with these limited attempts at engagement, far too many critical education decisions are being made in mahogany-lined offices by people who have little if any connection to the communities they have the privilege of serving.

Authentic community engagement is not a nice-to-have—it’s essential for our schools and our communities to thrive.

When we fail to foster truly collaborative, shared problem-solving that includes students, families, teachers, and community members alongside district and school leaders, we are wasting millions of dollars implementing programs that don’t last and leaving critical resources and assets on the table. What’s worse, we are missing critical opportunities to improve schools so that all of our students receive the support they need to succeed. Authentic community engagement is not a nice-to-have—it’s essential for our schools and our communities to thrive. So it must be a priority for education leaders at the policy, school, and classroom levels to develop the skills to do it right.

The Pillars of Community Engagement

TNTP’s community engagement work launched two years ago in an effort to learn about the current landscape of engagement efforts, articulate a new approach to engagement rooted in the very best work happening across the country, and help more districts and schools integrate effective engagement practices in their core work.

Over a year of observations, focus groups, and conversations with folks on all sides of the table, we’ve come to believe that authentic community engagement starts with four key ideas:

Shared Vision

Communities and school systems must first work closely together to shape a common vision for student success and make sure that everyone—from teachers to parents to community leaders—have a role to play in that vision. For example, in Camden, New Jersey, district leaders spent a year gathering input from parents, students, and community members to build a strategic plan that truly captured the community’s priorities—and then followed up through an extensive feedback campaign the following year to make sure the district was meeting the community’s needs. In order to keep the priorities of students front and center, central office staff members were linked with individual students.

Intentional Culture & Diversity

To build trust—especially in communities that have experienced divestment—schools must address bias, understand the unique context and assets of specific communities, and encourage the sharing of diverse perspectives. In Houston Independent School District, for example, more than 3,200 individuals worked together to select a new superintendent who was best positioned to meet the unique needs and culture of the district.

Authentic Collaboration

Families and community organizations are critical to student success. Schools need to share data and resources that can help families and community organizations better support student learning outside of school. The director of an after-school program in Arkansas recently confided his frustrations with local schools. Through his program, which provides students with academic and extracurricular support, he builds trusting relationships with students and knows when they are struggling or frustrated. He is in a great position to collaborate with schools to help every student succeed. Yet he hasn’t been treated as a valued partner or ally by his students’ schools—or even respected as a professional.

360-Degree Communication

Sharing information regularly and transparently is critical, but it’s not enough. Schools must create meaningful opportunities for all voices to be heard—and families and communities need to know how their feedback was incorporated into decision-making. In Shelby County Schools in Memphis, Tennessee, the district brought parents, students, school employees, and community partners together over the course of six weeks to develop solutions to inequities they identified together.

Resource: TNTP’s Community Engagement Feedback Loop

The Community Engagement Compass

There are bright spots of authentic community engagement practices around the country. To support more districts in building strong community partnerships that will lead to better outcomes for kids, we’ve developed a diagnostic tool we call the Community Engagement Compass.

By evaluating a district’s community engagement efforts across eight domains, the Compass is designed to paint a comprehensive picture of how engagement efforts are integrated across the core work of the district.

The Community Engagement Compass

In districts where we’ve piloted the Compass, the process is surfacing a wide range of best practices for engagement, while also highlighting areas for improvement:

In Brevard County, Florida, which is diversifying rapidly, Brevard Public Schools recognizes that the community it serves is shifting, and welcomes that evolution. Brevard is a community where people care about their neighbors already—and they care about improving their schools, even if their own children are already grown and graduated. The new superintendent is eager to connect with the community, and launched a listening tour to build trust with families. And community engagement has become a fully integrated priority throughout the district, with a focus on collaboration between departments that partner with families. The district even created a new Partner in Education staff position, which helps schools establish and maintain business partnerships to benefit schools. The Compass report surfaced evidence of the district’s work to move away from one-off, top-down relationships to a comprehensive plan for authentic engagement that supports academic goals and reduces inequities, while also accounting for the district’s changing demographics.

In Durham, North Carolina, the city is blossoming. Durham Public Schools has invested substantially in improving engagement efforts over the past few years. Recently a task force of families and community members led an effort to revise the district’s student code of conduct, which resulted in substantial new investments in improving school culture. But there is still work to be done and trust to be built. The Compass surfaced opportunities to improve relationships between the school district and the growing Latinx community, build the capacity of principals and teachers to engage with families, and communicate a powerful story of Durham’s progress and potential. Perhaps most importantly, it’s time for the community to revisit their own vision for what’s possible in their schools. Where do they want to be in five years? What will it take to get there?

Authentic community engagement takes significant work and time. It goes far beyond surveys and one-off meetings. But these efforts shouldn’t be viewed as a burden. When districts and schools are engaging communities effectively, they are establishing an ongoing relationship with continual opportunities for feedback, celebration, and adaptation. When a district takes on the responsibility of creating pathways for truly engaged communities, they are telling families that they care about children. They are treating parents and caregivers as assets and allies in efforts to boost attendance, improve focus in the classroom, and ensure that every child receives a high-quality education that helps them unlock their unique gifts.

And if a community can come together to create sustainable change in their schools, why can’t they do the same to build stronger and more equitable communities beyond their schools, too? That’s the real promise and potential of the community engagement revolution. I can imagine that world. Now it’s time to start making it a reality.

On the Road With Dr. Blackburn: A Superintendent’s Listening Tour

In Brevard County, Florida, where we piloted our Community Compass Diagnostic, we met a community that cares about each other—the kind of people who want to improve their local schools for the sake of their neighbor’s children, even if their own children have long since graduated. And in Dr. Desmond Blackburn, now in his third year as superintendent of Brevard Public Schools, we met a district leader for whom community engagement is a deeply rooted priority.

Getting to know the priorities of the people he serves has never been a nice-to-have for Dr. Blackburn; rather, it is, as Dr. Blackburn describes it, “a mainstay” of his work—integrated with his strategic plan, and at the heart of how he intends to improve his students’ outcomes.

To start that work, Dr. Blackburn determined that he needed to learn about the community from the people themselves. In his first year as superintendent, he spent five months traveling around his district, visiting community organizations and teacher’s lounges, listening and learning from the people he would serve. His tour is an example of a best practice that can and should be replicated in school districts across the country.

Q: Can you tell us a little bit about Brevard Public Schools? Who are the people of Brevard?

A: We’re the 10th largest district in Florida. We serve around 73,000 students, here on the east coast, just southeast of Orlando. In terms of the walks of life represented here in Brevard, we have the space program and NASA, we have Port Canaveral, we have a lot of high-tech manufacturing industries. There’s a lot going on, and a wide variety of people and backgrounds. Our students are the children of all those people. One of the things that makes Brevard unique is that there’s a rich buy-in here to what education can do.

Q: Where did you get the idea to do a listening tour? What did you want to get out of it?

A: I came into Brevard, and I noticed during the interview process there were a lot of questions around my thoughts on community engagement. I gathered that community engagement was already a priority for the district. And, to be quite honest with you, community engagement is a part of the job that, one, I enjoy and, two, I see as a non-negotiable to getting anything done.

Q: Can you say more about that?

A: Here’s where I have to give a shout out to one of my former bosses. He’s the superintendent of Broward County, Rob Runcie. Working with him, I saw him take on some pretty large challenges. He led a school closure—a school repurposing initiative, which is the first time Broward had ever taken on something like that. What made difficult tasks like that actually happen was that he had and continues to have a great deal of community support. While the school closure started rocky, as you can imagine, at the end, it was pretty much a celebration that we were able to seek out financial efficiencies and launch new programs during the height of the recession. A lot of what made that possible was community engagement.

Q: When you undertook the listening tour, what were your big questions for the community?

A: I wanted the community to explain to me what made Brevard unique. And I wanted them to share with me, real simple: How are you feeling? Are there things that have gone well in Brevard Public Schools? What are the things that you feel have not gone so well? The last question really was what, if anything, do you feel your new superintendent needs to prioritize…yesterday?

For Dr. Blackburn, building relationships with his community is a critical piece of the work. He’s occasionally caught capturing a selfie with stakeholders along the way.

Q: What did you hear?

A: Well, we’re one of the highest performing school districts in the state, and our data points compare really well nationally as well. Essentially, what I heard was there’s great pride in the academic programs and offerings in Brevard. That was the positive. But the other side of the same coin was that we are challenged in creating access to some of these high-performing program offerings equally throughout the district. Some of the challenge is around geography—because we’re 25 miles wide but 75 miles long. The other disparity is around socioeconomic status. The perception was if you were more affluent and/or you lived in central and south Brevard, your access to high-performing programs was greater than someone living at/or below the poverty line and living in the northern, more rural section of Brevard.

Q: Can you talk about the process of the listening tour? What did it look like? How did you connect with people?

A: Right off the bat, I supplied our board members with a draft entry plan. I grouped individuals that I’d thought about visiting, and asked them as a sort of test, “Hey, what do you think about this list? Are there others that you want me to seek out?” I was leveraging the fact that I’m new, they’re not new, and they were elected by these people, so I trust that they would know which groups I needed to meet with.

Of course, my immediate stakeholder group consists of staff, parents, and students. I went out to schools and asked principals to have staff and students and parents come out to events. We used a lot of social media. Everywhere I went, I would ask people to either friend me, follow me, or connect with me on LinkedIn. I used that quite a bit to get people to come out.

Dr. Blackburn believes a listening tour isn’t just a one-time thing; it’s part of an ongoing process of getting to know his partners in the community.

I went to schools and then other groups—for example, chambers of commerce, rotaries, Kiwanis, other service organizations, ethnic and special interest groups, the NAACP. We have a Hispanic chamber of commerce here in Brevard. I covered those bases. I scheduled large group meetings with probably hundreds of people. And then I would do smaller group meetings and meet with individuals. If there was a key opinion leader in Brevard, I wanted her or his name. I would schedule a one-on-one with that person. That’s how my list of people was created.

The tour itself took place from July through late November, early December. It was many, many nights and weekends. During the day, I would go spend two or three hours at different schools, because I really wanted to target the teacher voice. I’d sit in the teacher’s lounge, and teachers would rotate in. I’d say, “Hey, I’m Desmond Blackburn. Here’s where I am, here’s where I’ve been, here’s what I think about a couple things,” just really quick. Then I’d ask those three power questions: What’s great about Brevard? What are the challenges? What do you want me to prioritize? I have a little black book. I would take notes in that, and then I’d bring it back to the office and put my notes in a spreadsheet.

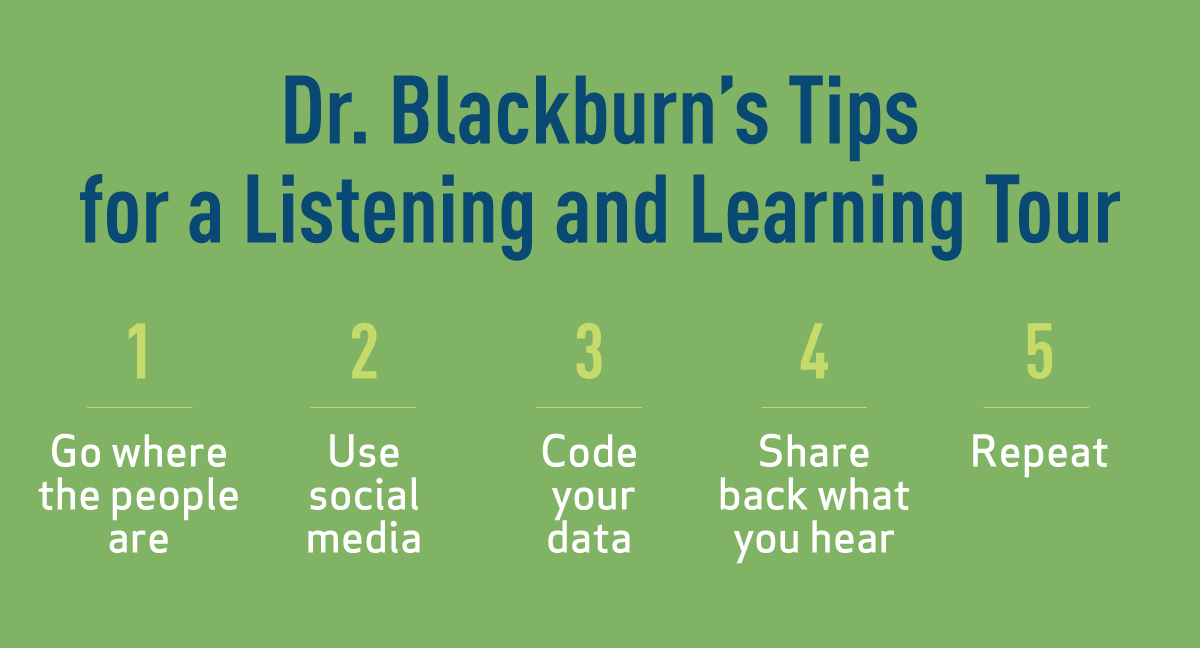

Resource: Dr. Blackburn’s Tips for Launching a Learning and Listening Tour

Q: We love spreadsheets. Tell us more.

A: I’m using some of the things I learned from project management, you know? I wanted to code each piece of information that I heard. So every piece of information went down the first column of the spreadsheet. Then I’d ask myself if this was a one-time piece of information, or if I’d heard it repeatedly. That was one code. Then I would code if this was a passionate plea or a minor plea. Right away, with those first two columns, I know the frequency and I know how passionate people are about this particular topic.

A bias that I’ve developed over the years is that when things are going really, really well or really, really badly, I can attribute that strength or weakness to one of three things: people, process, or policy. So I would code each item according to whether it was a people issue, a process issue, or a policy issue. Then in my monthly one-on-one meetings with board members, I would go through the list with them and have them rank the items in terms of—just subjectively—whether or not they feel this item is accurate and if so, whether or not they want to prioritize the issue. I did that individually with all five board members every month from July to November.

So far my spreadsheet is all subjective. You have what people are telling you and then you have what your board members are feeling. So then I gave an assignment to each of my cabinet members. Each cabinet member’s job was to take the items that fell in their wheelhouse and tell me whether or not objective data could be produced to either confirm or refute what I heard. At the end of that spreadsheet, we have a column that tells us, yes, data can confirm this; no, data refutes it; or not applicable, because we don’t have any data points to confirm or refute it.

Now this is the math guy coming out. At the end of that, I was able to hit a few sorting buttons and turn everything that I had heard into a set of priorities. I took all of that back to the cabinet, and we would mull over it for hours at a time. Through months and months of listening and learning, six priority areas emerged that we needed to tackle.

Q: Wow. So once those six priorities emerged, how did you start the process of turning that into action?

A: In December of that year, I asked the community to come to a town hall meeting. The ask was quite simple. “I heard everything you guys have said to me from July through late November. I feel that I understand it. I feel like I’ve organized it. I feel like we have some strategic priorities that I need to accomplish for you. But I need you to come and listen to me present it to the board, and then tell me thumbs up, I’m on the right track, or thumbs down, ‘You didn’t hear a word we said.’”

The place was packed. I’m talking all of Brevard. Again, we used a lot of social media to get the word out. My line was, “Hey, I’ve invested first. I came to you. Now I need you to come to me.” The community did not disappoint me at all. It was standing room only. We had to open up more rooms. We had the sheriff’s office doing traffic out front. It was great.

Q: That sounds amazing.

A: It was awesome. From that, we got the thumbs up from the community and the board. Then we spent the spring semester really fleshing out that strategic plan. Goals, objectives, timelines, all that good stuff.

Q: Can you talk about some of the work you’ve done in the past two years based on what you learned in the listening tour?

A: One thing we tackled was testing. This was huge. We had teachers and families and kids who felt like they were over-assessed. As a result, I’ve been calling on the state to do assessment reform. But in addition, I took a look internally and found that actually, we as a district were responsible for creating and administering a bunch of tests that, quite frankly, we did nothing with. We looked at all the tests we were administering as a district, and checked to see how the data was being used. If I could not find a situation where data from that test was being used in the transformation of a learning environment—if the data wasn’t being used to track student progress and make changes based on that—then we did away with that test. We eliminated close to 200 locally administered tests.

Q: What are you doing next to continue the conversation with families?

A: I like to do community. It’s just what I enjoy doing. It’s one of the perks of the job. But last year, I didn’t do a listening and learning tour. I basically said, “Okay, listen. We heard from you, now we’re working on the work this year.” This year, year three, I’m doing a new listening and learning tour. Looking at my calendar, I’m already going to hit more groups and more people than I did two years ago.

Q: What are you hoping to do differently this time?

A: There are really four messages. It’s reminding people what I heard two years ago, telling people what we did as a result, talking about the successes and continued challenges, and then asking what’s next. What else should we prioritize? It’s the “what’s next” part where I hope to gain the most. That’s where I hope to hear things like, “Hey, we know you’ve had a success, but this has been a major pain point for us.” Or, “Hey, we noticed you prioritized this piece and that wasn’t anything that was a part of the strategic plan. Why?” Either a compliment or critique. It doesn’t matter which one.

Q: What would you tell superintendents who want to take on this kind of listening tour?

A: If you’re going to do this, it requires the reappropriation of both time and money. It’s an investment. To make the most of it, you also need to have a system for organizing the information you receive. People are going to tell you all kinds of things. Without some process of coding what you hear, you might end up on a goose chase somewhere.

Finally, I don’t think any of this would be effective without social media. What did superintendents do 20 years ago, without Twitter or Facebook? If you’re not using social media, you’re missing out on opportunities.

Language Isn’t a Barrier—It’s an Opportunity

For three weeks this past summer, while many other kids in Durham, North Carolina were watching TV or running through sprinklers, students who recently emigrated from Mexico, Somalia, Syria, countries in Central America and central Africa and elsewhere headed back to school.

Approximately 140 families of English Language Learners signed their children up for Durham Public Schools’ ESL Newcomer Academy, a lively program enabling kids who have been in the country less than two years to participate in project-based learning with the goal of increasing their English, math, and technology skills.

Milkana Tesfazsi, a rising seventh-grader, emigrated with her mother from Ethiopia last winter. She recently told a reporter from the Durham Herald-Sun that she hopes to put her love for science to good use one day.

“I like America and I don’t want to move from North Carolina,” she said. “I want to be something, I want to be a doctor.”

Collaborating With Families of English Language Learners

Durham Public Schools (DPS) serves over 4,500 English Language Learners, who together speak more than 90 different languages. The district’s not particularly unique in this regard. Nationwide, some 10 percent of all students are English Language Learners—and that number is rising every day. For many school systems, it’s a dramatic demographic shift.

It is also an opportunity. Students who can navigate different languages and cultures bring tremendous value to their classrooms and, down the road, their colleges, workplaces, and communities. And the ability to communicate in multiple languages is a skill that will only be in demand for more and more jobs in a global workforce.

Students who can navigate different languages and cultures bring tremendous value to their classrooms and, down the road, their colleges, workplaces, and communities.

And yet nationally, English Language Learners as a whole are underserved. Too few students attend classrooms in which language learning and rigorous content are effectively integrated. Often, English Language Learners are lumped in with students with a wide spectrum of special needs, so they miss out on support tailored to the unique challenges of learning new content while learning a new language.

And frequently, their teachers aren’t provided with the right level of training and support. Only 15 percent of teacher preparation programs have course work on supporting English Language Learners. As a result, just 63 percent of English Language Learners graduate from high school, compared to 82 percent of students overall, and less than 2 percent of those who do graduate take the ACT or the SAT. In other words, too many English Language Learners are missing out on the opportunity to reach their full potential in school, and in life.

As the head of the English as a Second Language Services program in Durham, Sashi Rayasam wants to do better than that in her district, and has high expectations for the students she serves. Under the district’s new strategic plan, staff are committed to seeing high growth from 80 percent of English Language Learners.

But students aren’t the only focus for DPS. Rayasam is also committed to family engagement, pointing out that it’s critical to provide parents with the support they need to ensure their children’s success. All families are crucial partners in their children’s learning, and family engagement in education is linked to improved school readiness, higher grades and test scores, better attendance, and the increased likelihood of high school graduation. And families of English Language Learners are particularly motivated to ensure that their children succeed in school. After all, many recent immigrants cite their desire to provide a better life for their children as their primary reason for coming to the United States.

A recent survey by Learning Heroes found that parents who identify as “Spanish-dominant” (the only subgroup of English Language Learner parents identified by the survey) expressed greater interest than other families in a wide range of resources, including homework support, activities to support math and English skills, explanations of expectations for their children’s learning, and tips for advocating for their children’s needs.

Ask the Parents

In addition to supporting family engagement at the school level, Durham Public Schools also has a suite of resources available to the families of English Language Learners. At Durham’s ESL Resource Center, families who speak languages other than English have access to trained interpreters who can provide special support with enrollment and other services. DPS also employs a number of full-time Spanish Community Liaisons, who offer translation support at district-wide events and provide workshops on topics ranging from literacy, math, and college access.

“We’re committed to serving all of our families here in Durham—those who have been residents for a long time, those who are new here, those who speak English as a second language, and those who are refugees,” said Chip Sudderth, Chief Communications Officer. “Every family has a role to play to help children in Durham learn, grow, and succeed.”

In a national atmosphere in which immigrants and refugees have increasingly been targeted for harassment and intimidation, DPS has issued multiple statements affirming the right that all children in the United States are entitled to equal access to education, regardless of national origin, citizenship, or immigration status (read the district’s statements here and here.) District leaders see this as a critical step to ensure that all families feel that their schools are welcoming places, regardless of citizenship status—something that’s becoming even more important given the administration’s recent announcements about phasing out DACA.

As our nation continues to become more diverse, it’s critical that schools and districts recognize the important role they play in helping recent immigrants become integrated into the fabric of American society.

As our nation continues to become more diverse, it’s critical that schools and districts recognize the important role they play in helping recent immigrants become integrated into the fabric of American society. Too often, families of English Language Learners report heartbreaking stories of isolation and exclusion from parents, even as they actively seek to support their children’s learning.

Even in a district like Durham, there is still work to be done in this regard. As part of our Community Engagement Compass, we partnered with El Centro Hispano to host a roundtable conversation with the parents of English Language Learners. While some families reported strong relationships with their children’s teachers and principals, others shared stories of challenging language barriers, slow response times from principals and teachers, and subtle signs that their contributions as parents were not valued by school staff.

Resource: Ideas for Strengthening Partnerships With Families of English Language Learners

Next Steps for Schools

So what can schools and districts do to build stronger partnerships with families of English Language Learners? In Durham and elsewhere, it starts with the same principles that they’d use to engage all families: asking questions, creating pathways for ongoing conversations, making teachers and principals more accessible for working parents. But there are also specific steps that schools could and should take to make sure that non-English-speaking families are not left out.

For starters, schools can make the language or languages of their families visible and welcome. Translating school signage is a simple first step; staffing front offices with bilingual employees or volunteers and having trained interpreters available for parent-teacher meetings and family events is a longer-term investment. Schools can ask parents (in their native language) what kinds of resources they’d use for supporting their children’s learning at home. Individual teachers can figure out what kind of communication tools their students’ parents prefer—translatable text messages, for example, may feel more accessible than phone calls. And schools and districts can create strong programs—similar to Durham’s ESL Newcomer Academy or the ESL Resource Center—that provide English Language Learners and their families with extra support to ensure that students thrive.

Some of these steps are larger investments, while others are simple things schools can do right away. Regardless, it’s no longer an option to ignore the important role families of English Language Learners play in supporting student success, or to assume that a one-size-fits-all approach to engagement will work for all families. Families of English Language Learners aren’t a rare exception, nor are they a “problem” to be solved. They’re a valuable part of school communities, and it’s time to treat them as such. The success of growing numbers of students depends on it.

A Parent’s Bill of Rights

As parents, we want what’s best for our children, both inside and outside of school. We want to help our children to reach their full potential while making sure they have everything they need to be happy, fulfilled, and financially stable adults.

And if we feel that our children don’t have access to the resources they need to succeed, we won’t rest until we fix the problem.

If your child’s school doesn’t yet realize the power of strong partnerships with families, you don’t have to stand by and wait for your school to come to you. You have the right to be treated as an active, valued partner in your child’s learning, and we encourage you to advocate for that right.

You have the right to be treated as an active, valued partner in your child’s learning.

It’s up to us as parents to hold our schools and districts accountable for building strong relationships with families and community organizations. Let them know how your child learns best and what you expect for your child. Even if you don’t yet feel comfortable being highly visible or vocal, there are questions you can ask of your child’s teacher and principal that will give you a sense of what’s going on in the classroom—and will let your school know that you have high expectations for them.

Most importantly, as a parent, you have more rights than you might think when it comes to your child’s education. Here’s what you should expect from your child’s school and district:

I have the right to be treated as a valued partner in my child’s learning.

- I feel welcome in my child’s school and classroom. I have the contact information for my child’s teacher and I know how to connect with my principal.

- Before the year begins, my school reaches out through introductory phone calls, welcome back events, or home visits. During the year, my child’s teacher gets in touch with me on a monthly basis to share my child’s successes, as well as challenges.

- I receive information from my school on a monthly basis about academic priorities and programs. If needed, all materials are translated into my native language and trained interpreters are provided to help me communicate with staff.

I have the right to know how I can support my child in school.

- I know exactly what my child needs to master this year to be on track to meet his or her goal of being prepared for college, career, entrepreneurship, and service to the community. I am provided with information about how I can support my child in reaching those goals.

- I know how my child is progressing academically compared to his or her peers, and I know how my child’s school is performing compared to other schools in the area.

- At the first sign that my child is struggling, teachers reach out to me right away to let me know and work with me to create an action plan so that we can intervene before it’s too late.

I have the right to have my voice heard.

- When I reach out to someone at my child’s school, I receive a response within 24 hours.

- My school offers flexible scheduling for parent-teacher conferences and gives me alternative methods of communicating with teachers if I’m unable to come in person.

- My school and district creates regular opportunities for me to share feedback. They welcome my perspective and give me opportunities to learn about potential policy and program changes early on, so I can weigh in before decisions are made.

I have the right to a school and district that treats my family as a priority.

- I hear teachers, principals, and district leaders talk frequently about the role that families and communities play in student success—and I see them practice what they preach.

- I have regular opportunities to build my capacity as an advocate for my child and expand my content knowledge in subjects like math and English, so I can better support my child’s learning at home.

- When I need help accessing additional resources to support my child, I know where to look and who I can turn to for help.

Resources

For Districts

For Schools

- Strengthening Partnerships With Families of English Language Learners

- Dos and Don’ts for Communicating With Families (Flamboyan Foundation)

- A Guide for Engaging ELL Families: Twenty Strategies for School Leaders (Colorín Colorado)

- Assess Your Current Family Engagement Work (Flamboyan Foundation)

- Successful Family Engagement in the Classroom (Flamboyan Foundation)

For Families

Related Topics

Stay in the Know

Sign up for updates on our latest research, insights, and high-impact work.

"*" indicates required fields

A teacher leads a one-on-one reading session focused on strategy and engagement.

About TNTP

TNTP is the nation’s leading research, policy, and consulting organization dedicated to transforming America’s public education system so that every young person thrives.

Today, we work side-by-side with educators, system leaders, and communities across the nation to reach ambitious goals for student success.

Yet the possibilities we imagine push far beyond the walls of school and the education field alone. We are catalyzing a movement across sectors to create multiple pathways for young people to achieve academic, economic, and social mobility.