Op-Ed: Teaching for America

When I came to Washington in 1988, the cold war was ending and the hot beat was national security and the State Department. If I were a cub reporter today, I’d still want to be covering the epicenter of national security — but that would be the Education Department. President Obama got this one exactly right when he said that whoever “out-educates us today is going to out-compete us tomorrow.” The bad news is that for years now we’ve been getting out-educated. The good news is that cities, states and the federal government are all fighting back. But have no illusions. We’re in a hole.

Here are few data points that the secretary of education, Arne Duncan, offered in a Nov. 4 speech: “One-quarter of U.S. high school students drop out or fail to graduate on time. Almost one million students leave our schools for the streets each year. … One of the more unusual and sobering press conferences I participated in last year was the release of a report by a group of top retired generals and admirals. Here was the stunning conclusion of their report: 75 percent of young Americans, between the ages of 17 to 24, are unable to enlist in the military today because they have failed to graduate from high school, have a criminal record, or are physically unfit.” America’s youth are now tied for ninth in the world in college attainment.

“Other folks have passed us by, and we’re paying a huge price for that economically,” added Duncan in an interview. “Incremental change isn’t going to get us where we need to go. We’ve got to be much more ambitious. We’ve got to be disruptive. You can’t keep doing the same stuff and expect different results.”

Duncan, with bipartisan support, has begun several initiatives to energize reform — particularly his Race to the Top competition with federal dollars going to states with the most innovative reforms to achieve the highest standards. Maybe his biggest push, though, is to raise the status of the teaching profession. Why?

Tony Wagner, the Harvard-based education expert and author of “The Global Achievement Gap,” explains it this way. There are three basic skills that students need if they want to thrive in a knowledge economy: the ability to do critical thinking and problem-solving; the ability to communicate effectively; and the ability to collaborate.

If you look at the countries leading the pack in the tests that measure these skills (like Finland and Denmark), one thing stands out: they insist that their teachers come from the top one-third of their college graduating classes. As Wagner put it, “They took teaching from an assembly-line job to a knowledge-worker’s job. They have invested massively in how they recruit, train and support teachers, to attract and retain the best.”

Duncan disputes the notion that teachers’ unions will always resist such changes. He points to the new “breakthrough” contracts in Washington, D.C., New Haven and Hillsborough County, Fla., where teachers have embraced higher performance standards in return for higher pay for the best performers.

“We have to reward excellence,” he said. “We’ve been scared in education to talk about excellence. We treated everyone like interchangeable widgets. Just throw a kid in a class and throw a teacher in a class.” This ignored the variation between teachers who were changing students’ lives, and those who were not. “If you’re doing a great job with students,” he said, “we can’t pay you enough.”

That is why Duncan is starting a “national teacher campaign” to recruit new talent. “We have to systemically create the environment and the incentives where people want to come into the profession. Three countries that outperform us — Singapore, South Korea, Finland — don’t let anyone teach who doesn’t come from the top third of their graduating class. And in South Korea, they refer to their teachers as ‘nation builders.’ ”

Duncan’s view is that challenging teachers to rise to new levels — by using student achievement data in calculating salaries, by increasing competition through innovation and charters — is not anti-teacher. It’s taking the profession much more seriously and elevating it to where it should be. There are 3.2 million active teachers in America today. In the next decade, half (the baby boomers) will retire. How we recruit, train, support, evaluate and compensate their successors “is going to shape public education for the next 30 years,” said Duncan. We have to get this right.

Wagner thinks we should create a West Point for teachers: “We need a new National Education Academy, modeled after our military academies, to raise the status of the profession and to support the R.& D. that is essential for reinventing teaching, learning and assessment in the 21st century.”

All good ideas, but if we want better teachers we also need better parents — parents who turn off the TV and video games, make sure homework is completed, encourage reading and elevate learning as the most important life skill. The more we demand from teachers the more we have to demand from students and parents. That’s the Contract for America that will truly ensure our national security.

Stay in the Know

Sign up for updates on our latest research, insights, and high-impact work.

"*" indicates required fields

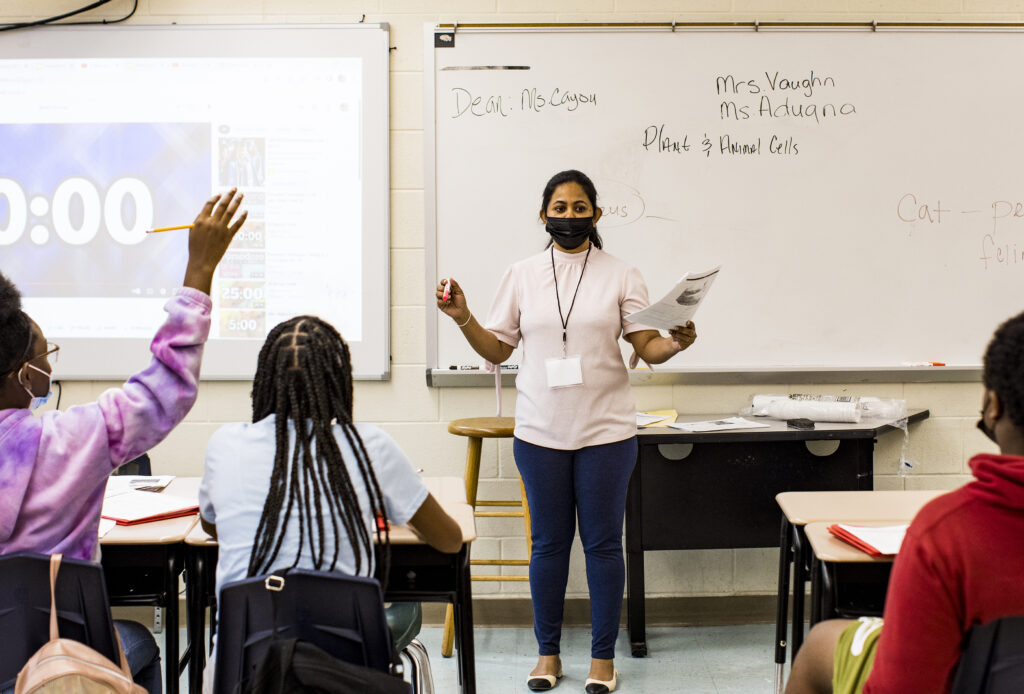

Imali Ariyarathne, seventh-grade teacher at Langston Hughes Academy, introduces her students to the captivating world of science.

About TNTP

TNTP is the nation’s leading research, policy, and consulting organization dedicated to transforming America’s public education system, so that every generation thrives.

Today, we work side-by-side with educators, system leaders, and communities across 39 states and over 6,000 districts nationwide to reach ambitious goals for student success.

Yet the possibilities we imagine push far beyond the walls of school and the education field alone. We are catalyzing a movement across sectors to create multiple pathways for young people to achieve academic, economic, and social mobility.