Across the country, we’re facing a massive shortage of bilingual educators. Meanwhile, my home country of Puerto Rico is a US colony with over 3 million American citizens who speak fluent Spanish and are mostly bilingual. Great place to recruit teachers, right? It’s not quite that simple.

In 2017, Puerto Rico had the highest high school dropout rate, unemployment rate, crime rate, and poverty rate in the United States. A social and economic crisis has been taking place on the island, and the education system lacked resources to prepare the next generation of Puerto Ricans to take on these challenges. The island needs great teachers, but the economic reality for most educators means they’ve had to look for opportunity elsewhere. School districts across the United States seeking bilingual educators have been eager to recruit from a pool of American citizens who perfectly meet this need—and Puerto Rico has been slowly drained of some of its most valuable talent.

Then Hurricane Maria hit, and a bad situation got worse. Over 100,000 people left the island, among them many teachers who took jobs in places like Houston, Dallas, Orlando, Miami and San Antonio.

I live in Dallas, but am originally from San Juan—so, this wasn’t just something I read in the news. I was living it. I work on teacher recruitment across Texas and have dedicated my career to getting all kids an excellent education. But a few months after the hurricane, I was on the phone with my old high school teacher, Mrs. Marrero—a person who was a crucial part of my learning and growth as a young person—and she told me several of her colleagues had made the decision to leave the island because they were recruited by school districts here in Texas and other states. The challenges of making a living as an educator in Puerto Rico have made this decision all too common. It hit me that I have become part of the problem.

The increasing demand for qualified educators—especially bilingual educators—has turned our recruitment efforts into what at times can feel like a battle for talent.

Talent raiding is when skilled workers, like teachers, are ushered from less privileged communities to wealthier communities. In my work helping districts fill their schools with great teachers, I often recommend they expand their recruitment to other cities. Though this isn’t really talent raiding, as we’re recruiting teachers for districts that genuinely need them—and aren’t historically privileged—that doesn’t mean those teachers aren’t still coming from communities that need them. Talent raiding doesn’t just happen between Texas and Puerto Rico, it happens between states and districts, too.

I know Dallas is not the only city that needs teachers. Houston, San Antonio, El Paso, Austin, and many of Texas’ smaller rural districts have the same need. It would be difficult to realistically meet the talent needs of the Dallas Metroplex without seeking to attract people from neighboring cities. The challenge becomes more pronounced when you factor in the immense need for bilingual teachers, too. Juan Pablo Martínez, Site Manager for several of TNTP’s projects across Texas for the past four years, had this to say about the challenge:

We do a great job helping districts staff their campuses by the first day of school, but I feel torn about some of the strategies that work so successfully in attracting that talent. While we can celebrate the success of ensuring every student has a qualified teacher when they return from summer break, we do so while ignoring the consequences our actions have on the districts that could have had those teachers had we not recruited them. The challenge is that teacher recruitment has become a zero-sum game—one district’s gain is another’s loss.

The increasing demand and lack of qualified educators—especially bilingual educators—has turned our recruitment efforts into what at times can feel like a battle for talent. This is expensive, so resources are prioritized to secure existing teachers, and not much is left to develop alternatives that could better address the root cause of the issue.

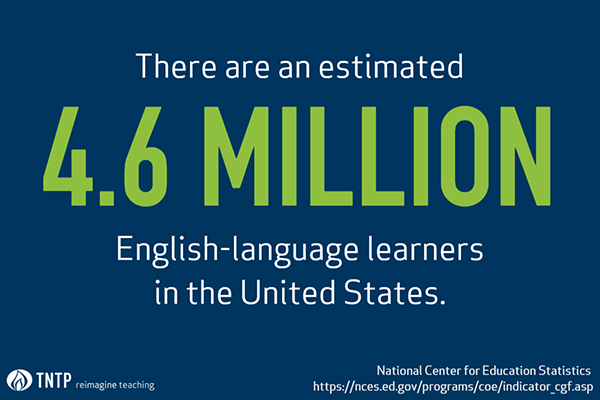

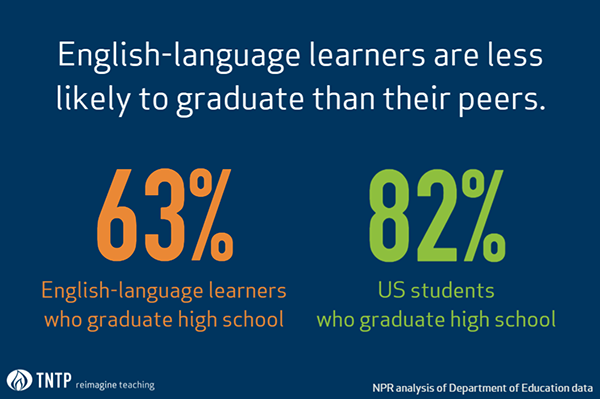

While everyone is negatively affected, there are relative winners and losers. The winners are students in public school districts, charters, and private schools that have greater resources and can make themselves more competitive in attracting talent. And the losers are students whose communities don’t have those resources, or are victims of factors outside their control—like natural disasters or social unrest. Winners experience brain gain while losers suffer brain drain. But as a whole, as a nation, nothing changes. We still don’t have enough great teachers—especially for our English-language learners.

With the large disparity between graduation rates for ELL students and other kids the United States, it’s crucial we create new ways to bring great ELL teachers into the classroom.

But we can change this. First, let’s look for longer-term solutions: We have such high English-language learner student populations entering the school system, but by the time they graduate, we end up with a shortage of bilingual teachers. Clearly, we’re failing to create viable pathways to teaching for our students. What can we do to encourage bilingual children to grow up into ELL teachers? Additionally, what can we do to give those aspiring teachers pathways to enter the profession without prohibitive costs, and pay them a living wage so they can keep at it? We need to do more to retain our best teachers—especially in distressed areas—and envision new ways to allow people who want to become teachers to do so.

I had an incredible childhood in Puerto Rico, and couldn’t be prouder of where I come from. I was surrounded by a community that loved me, and I had great teachers who cared. Any success I may have as an adult is in large part due to these positive circumstances, and I’m privileged to say that. But for so many young people in Puerto Rico today, these fundamental human rights are out of reach. As advocates for kids, is it our responsibility to fight for policies and work toward solutions for all children—or is it our priority to help our clients address their local teacher shortages? I think we can do both if we think differently about how we approach the challenge. Because to me, if we’re helping kids in one district while depriving those in another, we’re not doing our jobs. Let’s do better—sí se puede!