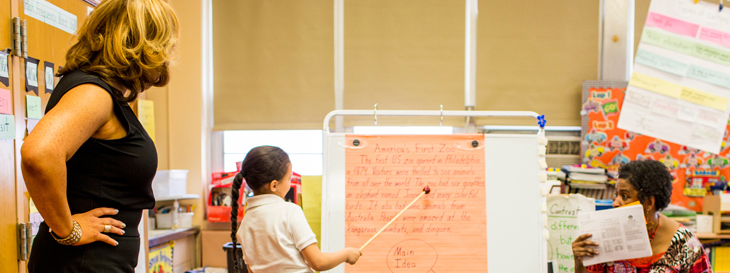

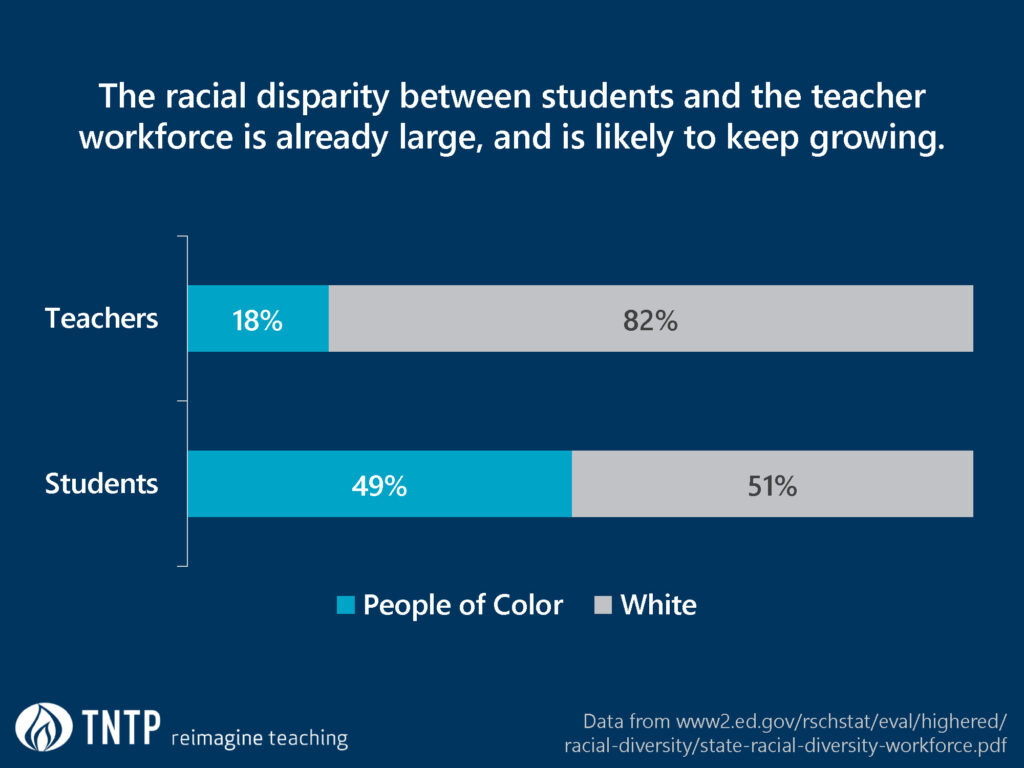

Imagine going from kindergarten through high school graduation without having a single teacher who looks like you. If you’re white, the thought has probably never crossed your mind: after all, more than 80 percent of teachers are white. But it’s a very real prospect for black and Latinx students, even at a time when students of color represent a growing majority in our public schools. In my home state of New York alone, 675,000 black and Latinx students attend schools with just one or no teachers of their same race.

This diversity gap in the teaching profession has real consequences for students. While all kids are more likely to thrive with diverse teachers, students of color with teachers of the same race are less likely to be suspended, more likely to be referred to gifted programs, and more likely to complete high school and go on to college.

It’s time to demand that education schools get serious about solving this problem and stop obstructing creative policy ideas that could help.

And this gap will only keep growing until we reckon with the root of the problem: education schools that, with relatively few exceptions, churn out a homogenous teacher workforce year after year. Data from the U.S. Education Department shows that almost three-quarters of teacher candidates in traditional education schools are white. Almost half of the largest preparation programs in the country (those with at least 100 students) enroll fewer than 10% black and Latinx students—and 95% of those programs were traditional education schools.

Many are large universities located in diverse communities. Consider The Ohio State University. It’s located in Columbus, Ohio, where people of color make up one-third of the population and two-thirds of public school K-12 enrollment. Statewide, 15 percent of students in public universities are black or Latinx. Yet black and Latinx students make up only 7 percent of Ohio State’s teacher preparation program.

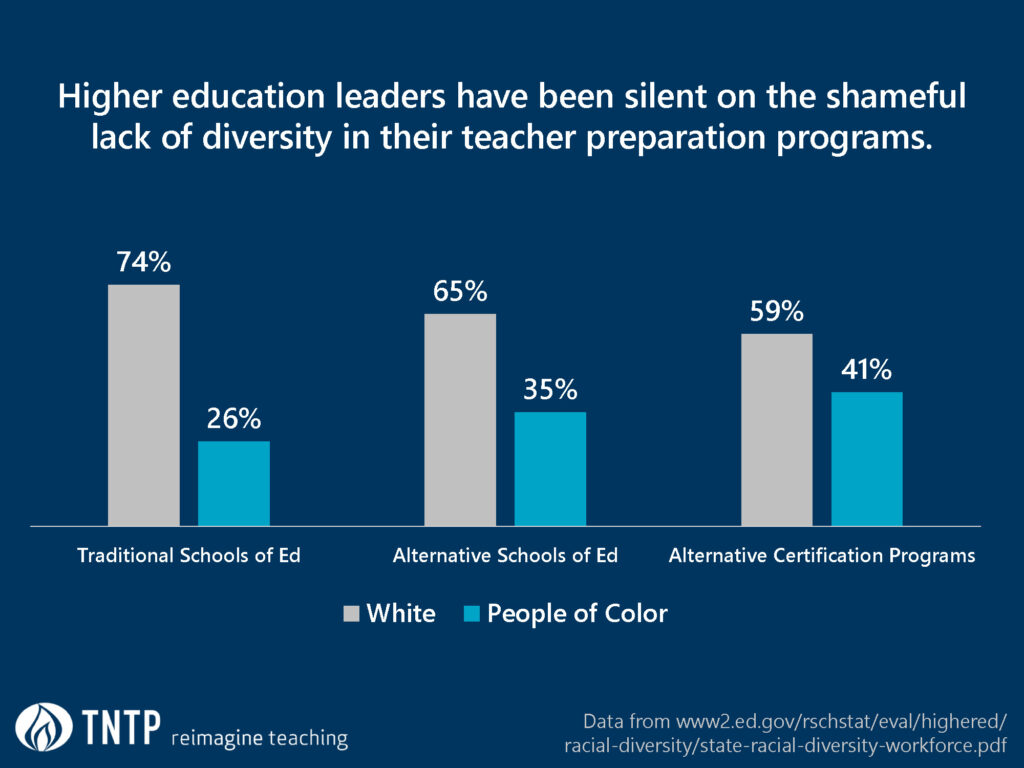

Unfortunately, most higher education leaders are silent not only on the shameful lack of diversity in their programs, but decades-long shortages of STEM, special education, and bilingual teachers. Those who say anything spend more time explaining away the troubling statistics than doing anything to change them. I’ve heard the whispers first hand: because students of color are more likely to attend lower-quality K-12 schools, the excuse-makers say, there just aren’t enough qualified candidates of color for undergraduate or graduate teacher prep programs to draw upon.

It’s an embarrassing excuse that reflects the same bias sustaining the racial achievement gap in the first place. It’s also empirically wrong. Undergraduate students majoring in education are less diverse than those pursuing other majors. Graduate students in education are less diverse than those studying other fields. If education schools just recruited the same percentage of students of color as other graduate programs, we’d have thousands more black and Latinx teachers heading into classrooms every year.

Preparation programs need to make diversity a genuine priority by setting goals for enrollment of students of color, completion, and placement, and formulating strategies to meet them.

Higher education leaders do, however, find time to raise howls of protest when anyone else tries to solve the problems they’re ignoring. Consider Columbia University’s Teacher College, one of the largest and most well-respected programs in New York. Just 16 percent of its students are black or Latinx, in a city where those groups represent 53 percent of the population. Yet according to Dirck Roosevelt, a professor at Teachers College, New York did “a terrible disservice to children” when the state decided to remove higher education’s monopoly on teacher preparation for high-performing charter schools—though research has shown that alternative certification programs tend to produce teachers who are more diverse and at least as effective as those who attend education schools.

Fortunately, there are some clear steps preparation providers and policymakers can take that could make our teacher workforce more diverse:

- First, preparation programs need to actually make diversity a priority, by setting goals for enrollment of students of color, completion, and placement, and formulating strategies to meet them (depending upon the demographics of the local college-age population, specific goals for black, Latinx, Asian, Pacific Islander and/or Native American representation are important). The New York City Teaching Fellows program, one of the biggest teacher training programs in the country and one my organization helped operate, does this and now recruits candidate pools that include more than 60 percent people of color–in the same city where Columbia Teachers College enrolls far fewer. State education departments can help programs prioritize diversity goals by weaving them into accountability systems, as states like Louisiana and Delware have already begun to do.

- Second, we need to remove barriers—especially financial barriers—that keep talented people of color out of teaching while doing nothing to ensure teacher quality. Becoming a teacher in most states costs upwards of $20,000 in tuition for master’s degree programs and testing fees for certification exams. The group that can afford this price tag is disproportionately white. Yet there’s no evidence that earning a master’s degree or passing many certification exams makes someone a better teacher (although there is evidence suggesting some of those exams are biased against candidates of color). How many thousands more talented people would be interested in teaching—including many paraprofessionals already working with students every day—if these meaningless financial burdens weren’t so prohibitive? It’s no coincidence that alternative certification programs, which tend to charge lower tuition or offer subsidies toward master’s degrees, are significantly more diverse than education schools.

- At the same time, we need to replace unhelpful barriers with more meaningful standards, so that demonstrated success in helping students learn becomes the ticket to a teaching license. Preparation programs should focus on the practical skills teachers need to be successful, and evaluate whether their candidates are actually mastering them. At TNTP, we’ve applied this approach in our own preparation programs, using a low-cost multiple-measures evaluation that predicts teachers’ long-term success more accurately than the stand-ins for teaching ability that most programs currently use.

A more diverse teacher workforce isn’t a cure-all for the inequities in our education system. But given the lack of diversity in teaching today and the stakes for students, it’s time to demand that education schools get serious about solving the problem and stop obstructing creative policy ideas that could help.