For a while now, we’ve been asking young people how their school experiences can be improved. This week, we released The Opportunity Myth, which digs into what we learned from nearly 4,000 students in five districts nationwide. Through listening to their perspectives and observing their experiences in school over the course of an entire year, it’s become unambiguously clear that students have big goals for their lives, but they aren’t prepared to meet them once they graduate from high school—not because they can’t master challenging material, but because they are rarely given a chance to try.

We’ve heard many reactions to these findings from other adults in the field, and we have plenty of ideas for how to move forward. But before we do, let’s remember the biggest lesson of The Opportunity Myth: Students are the top stakeholders in their educations, and we should listen to them before we claim we know what’s best for them. Today, we’re sharing reflections from six young people who joined us at the launch of The Opportunity Myth in Washington, D.C. on Tuesday, to find out how the report resonates with their school experiences, and what they believe we should do next.

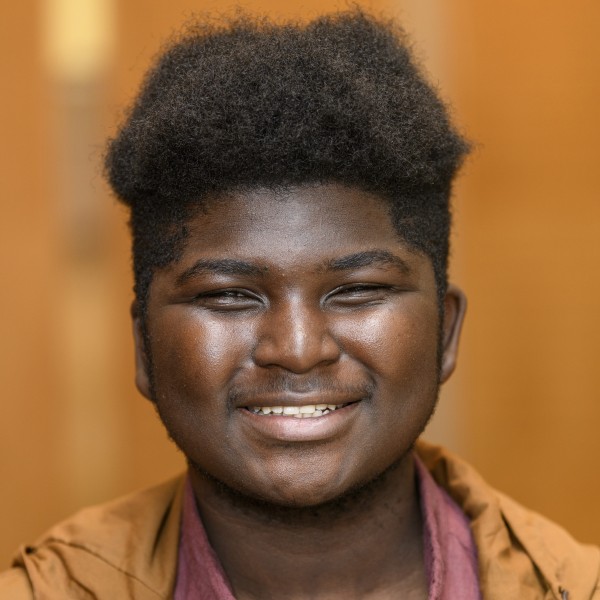

Vasiki Konneh, Colby College Class of 2020

My immediate reaction was basically, “Yeah, all of this makes sense. This is what I've seen. This is what I've experienced”—particularly the part about teachers having lower expectations for students of color, especially Black students like me. In high school, it seemed like my teachers expected that I would not do well academically just because of the color of my skin. I think a lot of Black students in my high school experienced that, too. It affected everyone differently, but the overarching result that I saw was kids didn’t care about their educations. It’s like, “If my instructor doesn't think I will succeed, why should I think I will succeed?”

When I got to college, the low expectations teachers had for me in high school affected me very badly. I had to unlearn what I had been taught about what I’m capable of; I had to teach myself that I can succeed. It was particularly difficult because I was doing this while in a rigorous college environment—so, I was doing two things at once. It was very mentally draining, but I did have an amazing support system of friends and faculty. Specifically, there were people of color from similar backgrounds to mine that shared their experiences with me and let me know that my aspirations were possible and that they were there for me. And I think that made my experience a little bit easier.

“When I got to college, the low expectations teachers had for me in high school affected me very badly. I had to unlearn what I had been taught about what I’m capable of; I had to teach myself that I can succeed.”

Julie Hajducky, Ninth-Grade Student, Member of Bridgeport Generation Now

Reading through the report, I connected to the fifth-grade student who felt that they were not reaching their potential in math, even though they loved the subject. Because a lot of the assignments weren't on grade level, the student was not receiving the attention and the connection to the curriculum they deserved and wanted. I love school—and want to be an education journalist one day—but in many of my classes right now, and throughout my school career, I haven't necessarily felt pushed.

At my high school, 100 percent of the student body is accepted into a four-year college or university, so I don't doubt that we’ll all get into college. But how many of us, once we get there, will be placed in remedial classes? How many of us will feel confused and unsupported in our college classrooms? When teachers place limits on the amount that we can learn, and I’m forced to say, “My learning stops here,” I feel like I’m less likely to be prepared for college when I get there. It's like hitting this glass ceiling that can’t be broken.

“When teachers place limits on the amount that we can learn, and I’m forced to say, “My learning stops here,” I feel like I’m less likely to be prepared for college when I get there. It’s like hitting this glass ceiling that can’t be broken.”

Martin Martinez Saldaña, UCLA Class of 2018, Member of Líderes

My reaction to The Opportunity Myth was so strong that I had to share it with my parents. I ended up having a two-hour conversation with my mom about the achievement gap and how fortunate my brother and I are to be in the positions we’re in. But more importantly, she and I talked about all that people of color have lived through and why I'm so passionate about being involved in work for social change. I think that’s when it finally settled in for my mom—and for me—that I’d survived a system that didn’t believe I could make it.

Going to UCLA has legitimized me in the eyes of a lot of people who don't even know me; the world sees me as “more valuable”—but I know so many other students who weren't given the opportunities I’ve had who are extremely valuable people. I want to use this privilege to advocate for my community, and to let those I love know they’re not alone.

“My reaction to The Opportunity Myth was so strong that I had to share it with my parents. I ended up having a two-hour conversation with my mom about the achievement gap and how fortunate my brother and I are to be in the positions we’re in. But more importantly, she and I talked about all that people of color have lived through.”

Kimberly Pham, Student at Temple University, National Council of Young Leaders: Opportunity Youth United Movement

I keep thinking about all the time kids waste in school. We spend most of our day there, then we go home, make dinner, and then we go back to school again. That’s a lot of time. So, I just want to let all educators know, even if you're not directly in the classroom, district supervisors, principals, and everyone in that brick-and-mortar setting, you play a critical role in our learning and how we feel about coming to school.

Parents and families set the bar high for school; they want us to get good grades, and they want us to learn. But the report showed me that the education system isn’t holding us to the same bar.

“Parents and families set the bar high for school; they want us to get good grades, and they want us to learn. But the report showed me that the education system isn’t holding us to the same bar.”

Megan Simmons, Barnard College Class of 2021, Member of Student Voice

While reading the report, I found myself nodding in agreement. The unwritten rules of my education system seemed to finally be written down and presented as fact. That was empowering. I made it to college, but only because I had parents and grandparents and aunts and uncles who went through the process before me.

I now work for Student Voice, a national student-run organization helping activate student voices to improve and change the education system—because we are the people are most affected by education policy, though we’re rarely asked our opinions on it. I talk to students across the country who have thoughts and opinions and ideas that they want to put into action. But, as said in the report, “School is not honoring their aspirations or setting them up for success.”

As we see in The Opportunity Myth, when students are challenged and taken seriously, when teachers give us opportunities to collaborate and think deeply, education becomes more than a stepping stone to the next grade—it becomes a tool to change the world.

“The unwritten rules of my education system seemed to finally be written down and presented as fact. That was empowering.”

Justin Thach, 12th-Grade Student, Member of Oregon Student Voice

Having moved from New Jersey to Oregon, I’ve experienced the disparity in education quality firsthand. The statistic that students in the report had access to grade-level material 26 percent of the time really jumped out at me and aligned with my experience. When you go to school, you generally expect to be challenged, and when you’re not, those low expectations become your expectations for yourself when you grow up. How are kids without grade-level material 74 percent of the time going to end up? What about that 74 percent of potential we aren’t going to see realized? I think it’s a big loss, and something we need to consider as a society.

As a high school senior, I can attribute a lot of the sense of agency I feel over my education to the teachers who really believed in me. When I’m in class and answer a question correctly, but my teacher puts that little bit of extra effort in to push my thinking—that’s when I truly grow and develop a sense of independence. Looking at the results of the report, that’s what we need to focus on moving forward, and getting all students grade-level material is an important place to start.

“When you go to school, you generally expect to be challenged, and when you’re not, those low expectations become your expectations for yourself when you grow up. How are kids without grade-level material 74 percent of the time going to end up?”

Read and share The Opportunity Myth—then take the first step by requesting your own free action guide featuring tools and advice to help more students in your community have worthwhile experiences in school.