In Brevard County, Florida, where we piloted our Community Compass Diagnostic, we met a community that cares about each other—the kind of people who want to improve their local schools for the sake of their neighbor’s children, even if their own children have long since graduated. And in Dr. Desmond Blackburn, now in his third year as superintendent of Brevard Public Schools, we met a district leader for whom community engagement is a deeply rooted priority.

Getting to know the priorities of the people he serves has never been a nice-to-have for Dr. Blackburn; rather, it is, as Dr. Blackburn describes it, “a mainstay” of his work—integrated with his strategic plan, and at the heart of how he intends to improve his students’ outcomes.

To start that work, Dr. Blackburn determined that he needed to learn about the community from the people themselves. In his first year as superintendent, he spent five months traveling around his district, visiting community organizations and teacher’s lounges, listening and learning from the people he would serve. His tour is an example of a best practice that can and should be replicated in school districts across the country.

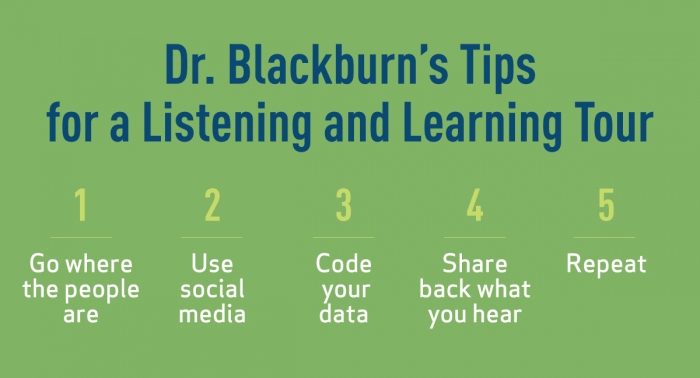

You can download Dr. Blackburn’s tips for launching a listening and learning tour, as well as several other resources for community engagement in our most recent publication, Walking Together: A Practical Guide for Strengthening Partnerships Between Schools, Families, and Communities.

Can you tell us a little bit about Brevard Public Schools? Who are the people of Brevard?

We’re the 10th largest district in Florida. We serve around 73,000 students, here on the east coast, just southeast of Orlando. In terms of the walks of life represented here in Brevard, we have the space program and NASA, we have Port Canaveral, we have a lot of high-tech manufacturing industries. There’s a lot going on, and a wide variety of people and backgrounds. Our students are the children of all those people. One of the things that makes Brevard unique is that there’s a rich buy-in here to what education can do.

Where did you get the idea to do a listening tour? What did you want to get out of it?

I came into Brevard, and I noticed during the interview process there were a lot of questions about my thoughts on community engagement. I gathered that community engagement was already a priority for the district. And, to be quite honest with you, community engagement is a part of the job that, one, I enjoy and, two, I see as a non-negotiable to getting anything done.

Can you say more about that?

Here’s where I have to give a shout out to one of my former bosses. He’s the superintendent of Broward County, Rob Runcie. Working with him, I saw him take on some pretty large challenges. He led a school closure—a school repurposing initiative, which is the first time Broward had ever taken on something like that. What made difficult tasks like that actually happen was that he had and continues to have a great deal of community support. While the school closure started rocky, as you can imagine, at the end, it was pretty much a celebration that we were able to seek out financial efficiencies and launch new programs during the height of the recession. A lot of what made that possible was community engagement.

When you undertook the listening tour, what were your big questions for the community?

I wanted the community to explain to me what made Brevard unique. And I wanted them to share with me, real simple: How are you feeling? Are there things that have gone well in Brevard Public Schools? What are the things that you feel have not gone so well? The last question really was what, if anything, do you feel your new superintendent needs to prioritize…yesterday?

What did you hear?

Well, we’re one of the highest performing school districts in the state, and our data points compare really well nationally as well. Essentially, what I heard was there’s great pride in the academic programs and offerings in Brevard. That was the positive. But the other side of the same coin was that we are challenged in creating access to some of these high-performing program offerings equally throughout the district. Some of the challenge is around geography—because we’re 25 miles wide but 75 miles long. The other disparity is around socioeconomic status. The perception was if you were more affluent and/or you lived in central and south Brevard, your access to high-performing programs was greater than someone living at/or below the poverty line and living in the northern, more rural section of Brevard.

Can you talk about the process of the listening tour? What did it look like? How did you connect with people?

Right off the bat, I supplied our board members with a draft entry plan. I grouped individuals that I’d thought about visiting, and asked them as a sort of test, “Hey, what do you think about this list? Are there others that you want me to seek out?” I was leveraging the fact that I’m new, they’re not new, and they were elected by these people, so I trust that they would know which groups I needed to meet with.

Of course, my immediate stakeholder group consists of staff, parents, and students. I went out to schools and asked principals to have staff and students and parents come out to events. We used a lot of social media. Everywhere I went, I would ask people to either friend me, follow me, or connect with me on LinkedIn. I used that quite a bit to get people to come out.

I went to schools and then other groups—for example, chambers of commerce, rotaries, Kiwanis, other service organizations, ethnic and special interest groups, the NAACP. We have a Hispanic chamber of commerce here in Brevard. I covered those bases. I scheduled large group meetings with probably hundreds of people. And then I would do smaller group meetings and meet with individuals. If there was a key opinion leader in Brevard, I wanted her or his name. I would schedule a one-on-one with that person. That’s how my list of people was created.

The tour itself took place from July through late November, early December. It was many, many nights and weekends. During the day, I would go spend two or three hours at different schools, because I really wanted to target the teacher voice. I’d sit in the teacher’s lounge, and teachers would rotate in. I’d say, “Hey, I’m Desmond Blackburn. Here’s where I am, here’s where I’ve been, here’s what I think about a couple things,” just really quick. Then I’d ask those three power questions: What’s great about Brevard? What are the challenges? What do you want me to prioritize? I have a little black book. I would take notes in that, and then I’d bring it back to the office and put my notes in a spreadsheet.

We love spreadsheets. Tell us more.

I’m using some of the things I learned from project management, you know? I wanted to code each piece of information that I heard. So every piece of information went down the first column of the spreadsheet. Then I’d ask myself if this was a one-time piece of information, or if I’d heard it repeatedly. That was one code. Then I would code if this was a passionate plea or a minor plea. Right away, with those first two columns, I know the frequency, and I know how passionate people are about this particular topic.

A bias that I’ve developed over the years is that when things are going really, really well or really, really badly, I can attribute that strength or weakness to one of three things: people, process, or policy. So I would code each item according to whether it was a people issue, a process issue, or a policy issue. Then in my monthly one-on-one meetings with board members, I would go through the list with them and have them rank the items in terms of—just subjectively—whether or not they feel this item is accurate and if so, whether or not they want to prioritize the issue. I did that individually with all five board members every month from July to November.

So far my spreadsheet is all subjective. You have what people are telling you, and then you have what your board members are feeling. So then I gave an assignment to each of my cabinet members. Each cabinet member’s job was to take the items that fell in their wheelhouse and tell me whether or not objective data could be produced to either confirm or refute what I heard. At the end of that spreadsheet, we have a column that tells us, yes, data can confirm this; no, data refutes it; or not applicable, because we don’t have any data points to confirm or refute it.

Now, this is the math guy coming out. At the end of that, I was able to hit a few sorting buttons and turn everything that I had heard into a set of priorities. I took all of that back to the cabinet, and we would mull over it for hours at a time. Through months and months of listening and learning, six priority areas emerged that we needed to tackle.

Wow. So once those six priorities emerged, how did you start the process of turning that into action?

In December of that year, I asked the community to come to a town hall meeting. The ask was quite simple. “I heard everything you guys have said to me from July through late November. I feel that I understand it. I feel like I’ve organized it. I feel like we have some strategic priorities that I need to accomplish for you. But I need you to come and listen to me present it to the board, and then tell me thumbs up, I’m on the right track, or thumbs down, ‘You didn’t hear a word we said.’”

The place was packed. I’m talking all of Brevard. Again, we used a lot of social media to get the word out. My line was, “Hey, I’ve invested first. I came to you. Now I need you to come to me.” The community did not disappoint me at all. It was standing room only. We had to open up more rooms. We had the sheriff’s office doing traffic out front. It was great.

That sounds amazing.

It was awesome. From that, we got the thumbs up from the community and the board. Then we spent the spring semester really fleshing out that strategic plan. Goals, objectives, timelines, all that good stuff.

Can you talk about some of the work you’ve done in the past two years based on what you learned in the listening tour?

One thing we tackled was testing. This was huge. We had teachers and families and kids who felt like they were over-assessed. As a result, I’ve been calling on the state to do assessment reform. But in addition, I took a look internally and found that actually, we as a district were responsible for creating and administering a bunch of tests that, quite frankly, we did nothing with. We looked at all the tests we were administering as a district and checked to see how the data was being used. If I could not find a situation where data from that test was being used in the transformation of a learning environment—if the data wasn’t being used to track student progress and make changes based on that—then we did away with that test. We eliminated close to 200 locally administered tests.

What are you doing next to continue the conversation with families?

I like to do community. It’s just what I enjoy doing. It’s one of the perks of the job. But last year, I didn’t do a listening and learning tour. I basically said, “Okay, listen. We heard from you, now we’re working on the work this year.” This year, year three, I’m doing a new listening and learning tour. Looking at my calendar, I’m already going to hit more groups and more people than I did two years ago.

What are you hoping to do differently this time?

There are really four messages. It’s reminding people what I heard two years ago, telling people what we did as a result, talking about the successes and continued challenges, and then asking what’s next. What else should we prioritize? It’s the “what’s next” part where I hope to gain the most. That’s where I hope to hear things like, “Hey, we know you’ve had a success, but this has been a major pain point for us.” Or, “Hey, we noticed you prioritized this piece, and that wasn’t anything that was a part of the strategic plan. Why?” Either a compliment or critique. It doesn’t matter which one.

What would you tell superintendents who want to take on this kind of listening tour?

If you’re going to do this, it requires the reappropriation of both time and money. It’s an investment. To make the most of it, you also need to have a system for organizing the information you receive. People are going to tell you all kinds of things. Without some process of coding what you hear, you might end up on a goose chase somewhere.

Finally, I don’t think any of this would be effective without social media. What did superintendents do 20 years ago, without Twitter or Facebook? If you’re not using social media, you’re missing out on opportunities.