Publication: Room to Run

Math Is Everywhere

David’s Class | 1st Grade at Diedrichsen Elementary School in Sparks, NV

When David Rivera got to first grade, he complained to his mom.

“It’s too much learning,” he’d say when he got home.

Trina Rivera says it was a big transition for David, 6, from kindergarten. “He said he didn’t like it at first because he didn’t get to play as much.”

But David’s feelings changed as he began to soak up knowledge in Connie Hall’s first-grade classroom at Diedrichsen Elementary School. Today, he’s bounding ahead in his math lesson, writing out multi-step addition and subtraction problems on his paper using equations, pictures (including a detailed drawing of 11 dogs), and complete sentences.

His mother couldn’t be more pleased to see David’s transformation into a confident first grader who’s mastering his numbers and reading. “Now he loves it. He’s really proud of himself.”

Ms. Rivera laughs as she recounts what happens when she helps David with his math homework. “He’s teaching me things. I’m like, ‘Wow! I didn’t know you could do that.’”

Number Crunchers

Sparks, Nevada is just east of Reno, a small city tucked between snow-capped mountains and neon lights. Diedrichsen Elementary, one of Washoe County’s 64 elementary schools, sits in a quiet residential neighborhood full of modest homes and apartment complexes. It serves around 400 students in an older building that, despite its dark hallways, manages to be full of light.

On a warm Wednesday morning, 17 first graders file into Connie Hall’s classroom, ready to start their day. They’re a good-natured bunch. Several bound up to their teacher and wrap their arms around her waist (as first graders do) for a quick hug.

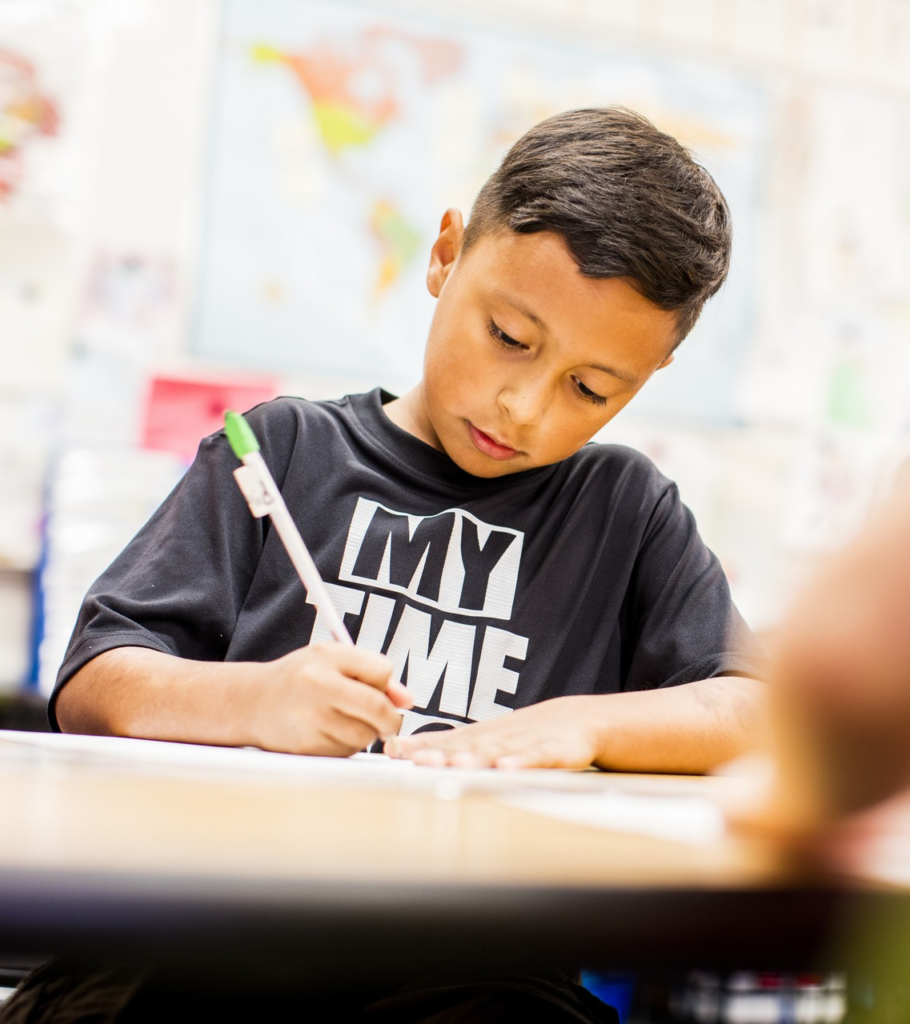

Ariel De Guzman gets down to business in math class.

In Mrs. Hall’s classroom, every child is expected to excel, and every child is expected to have fun in the process. That’s not because the class is without its external challenges. Diedrichsen houses a Social Intervention Program, a self-contained special education program whose goal is to reintegrate students with specific emotional and behavioral needs back into the general education setting. And around 50 percent of students at the school are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

But in Mrs. Hall’s classroom, nothing stands in the way of her students getting the most out of first grade—a critical year that will build an important foundation for their learning. As Mrs. Hall says. “I have students with IEPs. I have students who are English language learners. But you won’t be able to tell who’s who.”

It’s true. This morning, hugs taken care of and backpacks deposited in cubbies, the class sets to work right away for a short burst of math practice, drawing pairs of numbered cards from a basket in the center of the table and organizing them on their papers, using the symbols for less than, greater than, and equal to.

Britney Taelour, 6, explains that she knows which number is bigger by looking first at how many tens are in the number, then how many ones.

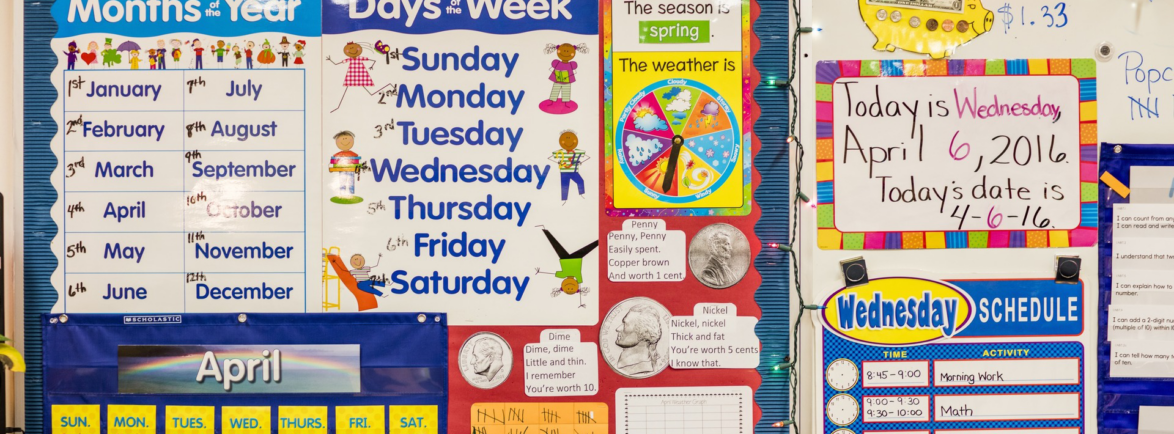

After a few minutes of comparing numbers, the class gathers on the rug in front of an elaborately decorated wall centered on a large calendar.

“Give those brains a kiss!” says Mrs. Hall, with a level of exuberance only an early elementary teacher could muster at this hour of the morning. The kids kiss two fingers and pat themselves on the foreheads affectionately.

“Our math brains are on this morning,” she says. “I heard some really good conversation going on.”

Now it’s time for Calendar Math, a quick morning routine that helps Mrs. Hall develop her students’ number sense before they even start the “real” math lesson. Together, they talk through the date, spell “Wednesday,” and figure out—counting by tens and then by ones— that today is the 129th day of the school year. This gives them occasion to talk about how they know 129 is an odd number.

“Okay, put your hand on your computer.” The class obliges, index fingers affixed to brains. “How many more days until we get to the next bundle? Lock in your answers.”

Her students, practically vibrating with energy, hold fists to their chests with thumbs up when they’ve determined their answers.

“One!” they exclaim.

“Now give me an equation that will tell me how to make the next bundle.”

She calls on Theresa Trowbridge, 6, who offers, “29 + 1.”

“Wow, that’s great. And what’s another equation we could use to do the same thing?”

Another student chimes in: “9 + 1!”

Mrs. Hall nods. “You all are really sharp this morning. Can I keep you all?”

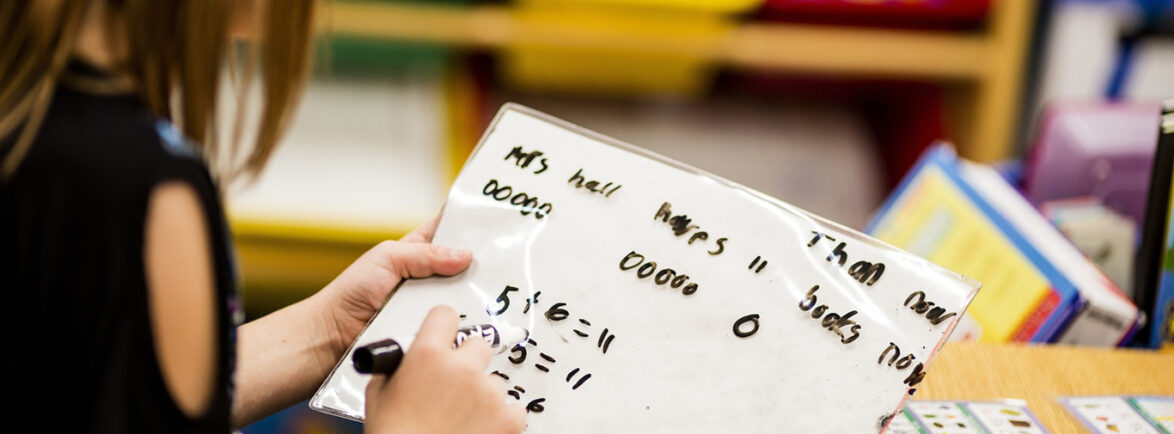

Mrs. Hall’s students engage in a quick math warm-up activity.

Laying the Foundation

Numbers are everywhere in Mrs. Hall’s classroom.

Her students make a tally mark for each day of school and count them by fives. They collect daily data on the weather so they can graph cloudy and sunny days. They count how many of their classmates are signed up for hot lunch. They count their missing teeth. Within the first 10 minutes of class, they’ve manipulated numbers in easily 10 different ways—and that’s before they’ve even started the day’s math lesson.

None of this is by accident.

Connie Hall, who’s been teaching elementary school for more than 20 years in public and private schools all over the country, believes using every moment of learning time is essential for leveling the playing field for all her students, regardless of the challenges they bring to school.

Connie Hall in her classroom.

“I have to maximize every moment from when they come in the door,” she says. “I’m using math informally, but it’s going into their brains. And they have to answer me in a complete sentence, too. You know how they talk about teachable moments? I try to use every possible moment of the day as a teachable moment.”

It’s hard not to marvel at Mrs. Hall’s knack for getting six-year-olds so absorbed in math first thing in the morning. But to truly appreciate what makes her class so special, you have to look close. Every day, Mrs. Hall is finding different ways to reinforce the same fundamental concept: place value in a base 10 number system.

In fact, Mrs. Hall’s students will spend most of the year building their understanding of numbers and operations in base 10 and operations and algebraic thinking, rather than jumping around to the 14 different mathematical topics your first-grade teacher probably tried to cover.

That’s because the basics of place value are part of a foundation that makes a host of more advanced math skills possible. When they get to second grade, a strong understanding of our number system will allow Mrs. Hall’s students to add and subtract increasingly large numbers and explain why various strategies work. In third, fourth, and fifth grade, they’ll be ready to compare and round large quantities and learn how to use all four operations conceptually (and efficiently).

You know how they talk about teachable moments? I try to use every possible moment of the day as a teachable moment.

– Connie Hall

These understandings even support students as they enter the world of fractions and decimals: They’ll be able to apply what they know to make sense of fractional quantities and make accurate calculations with them. By ninth grade, they’ll be ready to excel in algebra, which is especially important because it’s highly correlated with high school graduation and college success.

That progression and building upon of prior knowledge is the basic philosophy behind everything that happens in Mrs. Hall’s classroom—and it’s one she says is baked into the Common Core standards themselves.

“Each standard prepares the kids for the next thing,” she says. “In first grade, we work on adding and subtracting within 20, but students will build mastery and fluency with addition and subtraction up to 10. If they have that, the next year they’ll get to mastery and fluency with adding and subtracting within 20. Then they’ll begin working with numbers up to 100, and then the next year they’re adding 1,000. When every teacher is really giving them that focus and the students get it, they’re ready to add the next step. It’s a nice progression.”

In other words, Mrs. Hall is helping her students take the first steps on a carefully planned journey, even if the destination seems impossibly far off right now.

The Mother Ship

For Theresa Trowbridge, academic success—and from her mother’s perspective, independent living—once seemed not just far off, but perhaps impossible. Two-and-a-half years ago, Theresa was virtually non-verbal.

“She had about a dozen words in her useable vocabulary,” says her mother, Jamie Norlock. “That was our first clue that something wasn’t right.”

Theresa was diagnosed on the autism spectrum. “I thought, this can’t be. This isn’t my daughter,” says Ms. Norlock. “What really scared me was when I’m 90, is she still going to be living at home? Would she be able to take care of herself?”

Theresa at two-and-a-half was diagnosed on the autism spectrum. She was non-verbal. -Jamie Norlock

Theresa started preschool in a program for students with special needs. The teachers there were perfectly nice, says her mother, but it wasn’t the right setting for Theresa.

“I don’t want to say it dumbed her down, but there wasn’t enough stimulation for her. Academically, she’s very intelligent.”

Despite some anxiety about mainstreaming Theresa, Ms. Norlock enrolled Theresa in Diedrichsen for kindergarten. Today, as an exuberant first grader, the little girl who three years ago wasn’t saying much more than “mom,” “dad,” and “juice” is considered on par with her peers.

From Ms. Norlock’s perspective, there’s no question that Theresa has excelled as a result of a great teacher and a challenging academic environment.

“She lacks on the social skills sometimes,” Ms. Norlock acknowledges. “But when it comes to what she’s learning, Theresa has benefitted from being held to higher standards. Mrs. Hall knows what she’s capable of, and she doesn’t let her do subpar work.”

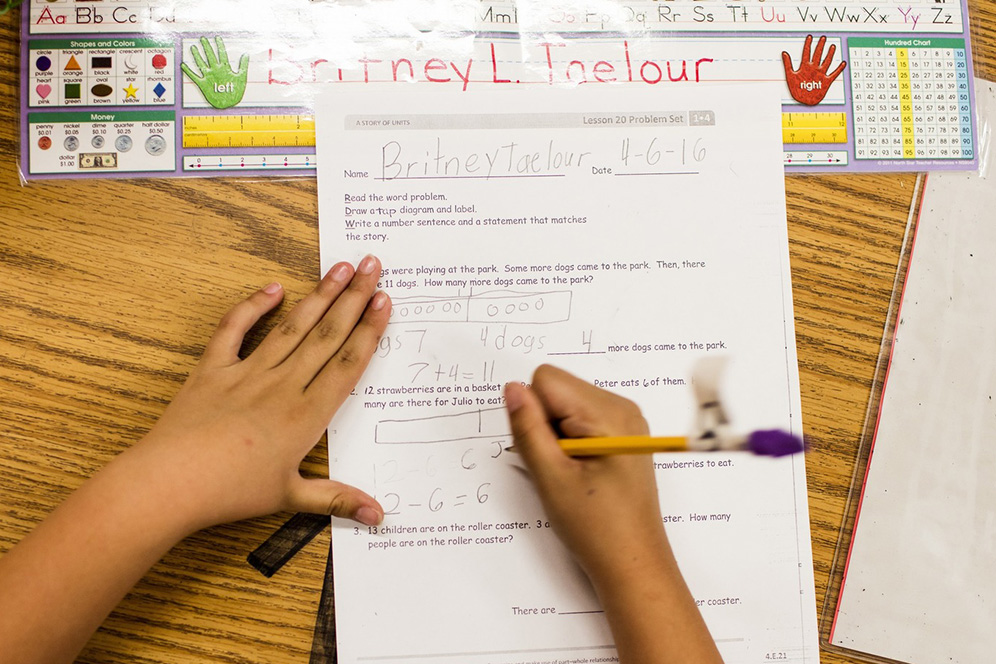

Britney Taelour works on multi-step addition problems.

Their morning routine complete, the class transitions to their “real” math lesson. Today, they’ll focus on word problems that ask students to solve for different variables: “There are 12 strawberries in a basket. Peter eats six of them. How many are left for Julio to eat?” or “There are six kids on the rollercoaster. Three adults are on the rollercoaster. How many people are on the rollercoaster?”

Mrs. Hall walks the class through an example problem using a tape diagram, which helps students visualize which pieces of a problem they know and which ones they’re looking for.

“There are nine dogs at the park. Okay, so what does the first sentence tell us? How many dogs were at the park?” she asks.

“Nine!”

“Okay, then some more dogs came to the park. Then there were 11 dogs. Now we’re going to solve to see how many more dogs came to the park.”

Even in first grade, Mrs. Hall’s students lead much of their own learning.

The kids read along with Mrs. Hall as she writes the problem in complete sentences on a paper that is projected on the wall using a document camera. She draws nine circles in a box, then draws an empty box next to it—her tape diagram. Under the diagram, Mrs. Hall writes the problem as an equation, leaving a blank square for the missing number.

“Okay, how would you solve to find that mystery number?”

The kids talk eagerly at their tables, and then return their attention “to the mother ship,” as their teacher says.

“We could use subtraction!”

“What subtraction equation could we do?” They pause, mulling it over. “Think of our family,” Mrs. Hall prods, reminding them of their fact families—their knowledge of how groups of three numbers relate to each other using addition and subtraction.

Quiet gasps of recognition spread around the room. “Eleven take away nine is twoooooo!”

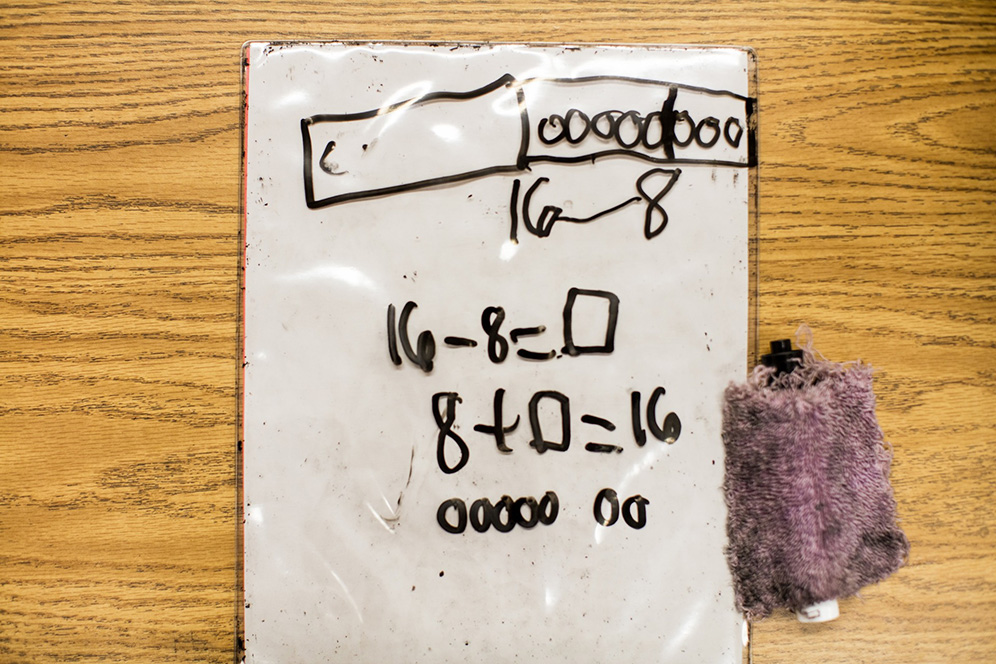

A student’s tape diagram.

The example problem solved, students break into groups at their tables to work through a set of similar but more complex problems, using tape diagrams, pictures, equations, and complete sentences.

Mrs. Hall circles the room, peering over shoulders. She asks the kids to explain their work to her, gently redirecting them when they’re off track.

At one table, Ariel De Guzman, 6, looks with pride at her tape diagram. “We’re trying to figure out the missing number that would make this equal 16,” she says.

Then Ariel explains the mistake she made. Originally, she thought the missing number was seven, but then she counted the circles in her drawing and realized that if she started with eight strawberries and needed to get to 16 strawberries, the missing number was actually eight: two more strawberries to get to a bundle of 10, plus another six more to get to 16.

Ariel’s mistake—and figuring out how to correct it—is part of her learning process, and she seems as pleased with the mistake as she is with the correct answer.

From Mrs. Hall’s perspective, that’s because the goal is to get her students to understand why numbers behave the way they do, and mistakes present opportunities to deepen that understanding. In her classroom, she’s created a safe space where every misstep represents a chance to learn something new.

“Give Me Some Gravy”

Moving from conceptual understanding to procedural skill, like Mrs. Hall’s students are doing, is a major goal for math in a Common Core classroom. Before Common Core, students would have gone straight to the procedures—leaving out the conceptual understanding that will help them build on these skills as they advance in their math learning.

“When they’re giving me an answer, I always say, ‘Give me some gravy.’ I want to see more. I want them to dig deeper,” says Mrs. Hall. “I want them to get to the point where they have a really solid foundation.”

To understand why this deep understanding of math is so important—and so different—think back on your earliest elementary school math memories. Chances are if you remember anything, it has something to do with reciting multiples of fives, or memorizing basic addition and subtraction facts.

Mrs. Hall supports Brooklynn Scambler as she identifies the equation that best solves a word problem.

Mrs. Hall’s students can tell you that adding 10 and two gives you 12. But they can also tell you why the answer is 12 and not, say, 30. They can write you the corresponding equation. They can draw you a picture showing that the number 12 literally translates into a 10 and a two. They can tell you when you’d need to add 10 and two in the real world, and figure out how many more you’d need to add to get 20.

As these students progress, they’ll bring with them their deep understanding of place value and operations to make sense of increasingly complex scenarios—and to make calculations easier. When they get to fourth grade, for example, Mrs. Hall’s students will recognize that in a multi-digit whole number, a digit in the ones column represents 10 times what it represents in the column to its right. Understanding that makes a problem like 700 divided by 70 a snap.

Before Common Core, math instruction was more “teacher-guided,” Mrs. Hall says. “The kids didn’t explore as much. You gave them information, they did a worksheet, and it was over.”

Today, her students are doing much more of the figuring out themselves. “They have to think more,” she says. “Before, it was like we were handing each student a completed cake. Now we’re giving them the ingredients and they’re putting it together. They have ownership of their work. They’re discovering. It’s less of the teacher, more of the student. I’m guiding and facilitating.”

The bottom line, as far as Mrs. Hall is concerned?

“I’m seeing more of a love for math, even with the kids who struggle. Now it’s more of a joy. I like them to have that moment. I like to see the light bulb go off, as opposed to just giving them everything.”

I’m seeing more of a love for math, even with the kids who struggle. Now it’s more of a joy. I like them to have that moment. I like to see the lightbulb go off, as opposed to just giving them everything.

– Connie Hall

Making Problem Solvers

More joyful learning is undeniably a good thing. But for Mrs. Hall, the bigger goal of this new approach to math instruction is to ensure students are exposed to the content and the cognitive load that will set them up for long-term success. That’s personal for her.

“When I was in school, it was mostly recall—skills on the lower levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy, like remember and understand. I was starting to feel that I wasn’t smart, because I wasn’t able to do those fill-in-the-blank or multiple-choice questions. When I started to get assignments that asked me to design or construct things, I started feeling like I wasn’t that bad after all.”

She believes the new standards offer a pathway to give many more children that same experience. “What I’m seeing with the standards is that the students who once thought they were ‘stupid’ or couldn’t learn are starting to feel success. They can do this work. This approach is reaching more students.”

David listens to Mrs. Hall as she sets up the day's math lesson.

That resonates with Trina Rivera, David’s mom, who marvels at how different her son’s school experience is from her own.

“I had a really hard time in school. By high school, I didn’t want to go anymore because I felt so far behind,” she says. “It makes me really happy that David’s not going to have a hard time like I did. I want him to go as far as he can.” She’s been blown away by what her son is able to do.

“He’s so smart. And he loves it. Whatever Mrs. Hall is doing, it’s great.”

It makes me really happy that David’s not going to have a hard time like I did. I want him to go as far as he can.

– Trina Rivera, Mother of David, 6

Ms. Norlock, Theresa’s mom, couldn’t agree more.

“Mrs. Hall holds the kids to that high standard. That’s only going to help them later on. They’ll be prepared for more challenging courses. They’ll be better problem-solvers. It’s going to make them stronger people, in my opinion.”

As for the little girl Ms. Norlock once worried would never be self-sufficient—now, her mother dreams of college and a fulfilling career for Theresa.

“I dropped out of college. I wish I would’ve kept going with my education,” she says. “So I tell Theresa all the time—you can do whatever you want, as long as you work for it.”

Theresa seems to have taken that message on board, both from her mother and from her teacher. When she gets stuck in math, Theresa explains, she goes back to the problem and tries again. She might try a different approach—draw a picture or a diagram. She’ll practice until she understands.

This doesn’t seem like a big deal to her: It’s just how she and her classmates roll. They are not just memorizing skills or formulas given to them by their teacher. They’re working their way toward the foundational knowledge that will be essential as they advance to more complex mathematical concepts. At the same time, they’re building the habits of lifelong learners—and they’re loving it.

They’ll be prepared for more challenging courses. They’ll be better problem-solvers. It’s going to make them stronger people, in my opinion.

– Jamie Norlock, Mother of Theresa, 6

Read Another Student's Story

Stay in the Know

Sign up for updates on our latest research, insights, and high-impact work.

"*" indicates required fields