Publication: Room to Run

Making History

Shatavia’s Class | 11th and 12th Grade History at North Star College Preparatory High School in Newark, NJ

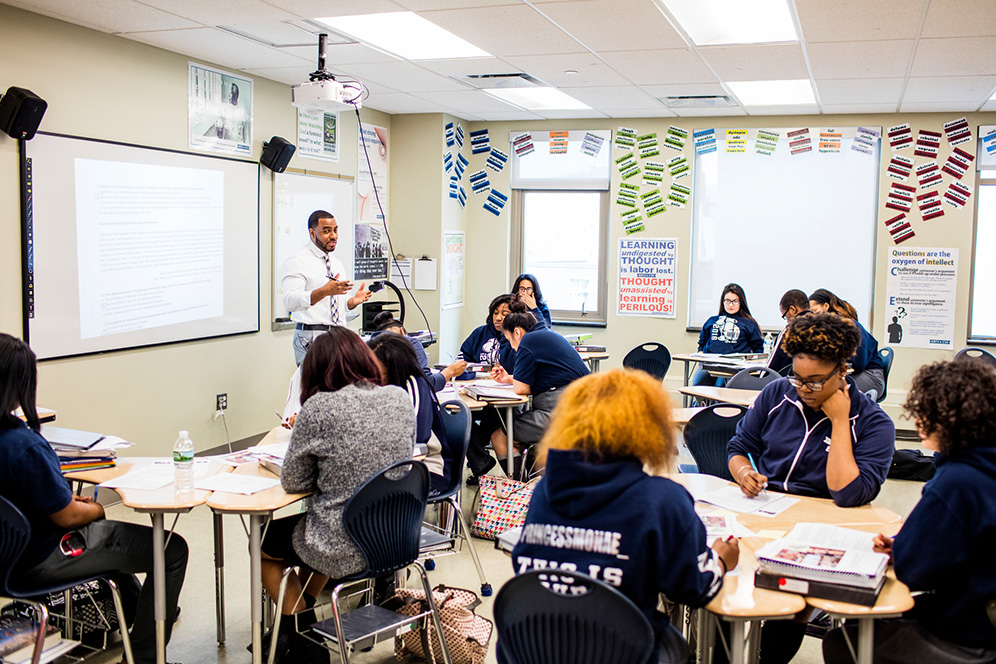

If you close your eyes in Art Worrell’s classroom and listen to his students discuss history, you’d never know you were in a high school classroom.

You probably wouldn’t guess that it’s a high school classroom where many of the students will be the first in their families to attend college, either. These young people could easily step into a college history course right now and excel.

But for Shatavia Knight, Mr. Worrell’s AP U.S. History class is about more than just being ready for college. For her, understanding history is about understanding the world she lives in—and preparing her to change that world.

“A lot of the things we talk about within this current time period happened as a result of history,” says Shatavia, 18. “We already know about racism, so now we need to know about the Civil Rights Movement, the Black Panthers. When you know history, you know why things are the way they are today.”

As far as her teacher is concerned, using history to turn his students into writers, readers, and thinkers who are ready not just to succeed in college, but also to become leaders and change agents, is exactly the goal.

“I Want to Know…”

Sitting on the corner of Broad Street and Central Avenue in Newark, New Jersey, North Star College Preparatory High School doesn’t look much like a school from the outside.

Here in Newark’s Central Ward, most of the neighborhood is commercial, with the local Rutgers campus in one direction and Newark Penn Station in the other. Between them are wide avenues of industrial buildings, corporate headquarters, and downtown shopping.

Students in Art Worrell’s history class are learning to analyze primary texts like historians do.

But inside North Star, the hallways are buzzing with a culture of learning. The entryway is lined with historic images of Newark. Upstairs, black and white portraits of students are on display in the halls. College pennants hang on classroom doors.

North Star is part of the Uncommon Schools network, which operates public charter schools serving 12,000 students in New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts. At North Star, 98 percent of students are African American and Latino, and 84 percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. In a city where more than one in four African American and Latino students doesn’t receive a high school diploma in four years, a vast majority of North Star students are graduating on time (90 percent of them), and their graduates have a 100 percent college acceptance rate.

In Mr. Worrell’s first period AP U.S. History class, his students have already tackled college applications. But as spring of their senior year settles in around them, no one here is slacking off. Today, they’re starting a new unit on Nixon’s domestic policies in the 1970s. They kick off by generating questions they want to answer in this unit.

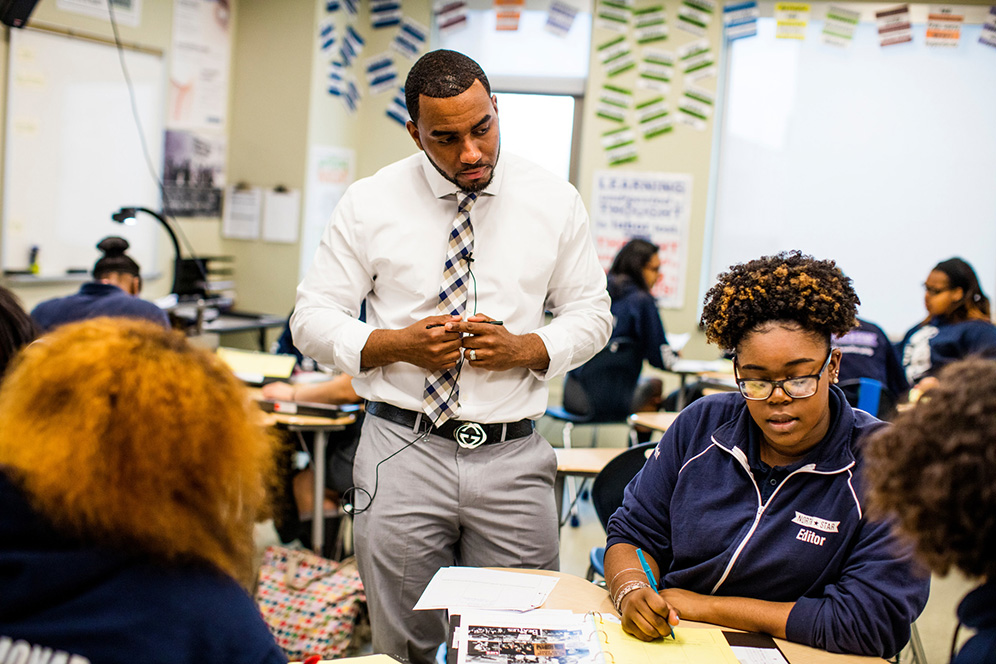

Shatavia Knight (center) discusses Nixon’s domestic policies with her group while Mr. Worrell looks on.

“I’d like to know if Cold War tensions escalated in the 1970s,” muses Michelle Veras, 17.

“Absolutely,” says Mr. Worrell. “We will be looking at detente and Nixon’s Cold War policies. That’s going to be a huge question looming over the country.”

“I want to know how Nixon’s Watergate scandal and almost impeachment affects America and American pride,” says Shatavia.

“Great,” says Mr. Worrell. “That connects back to that essential question of declining expectations in the 1970s. Good question.”

As they kick around a few more questions—on progress with women’s rights, Nixon’s War on Poverty, and Gerald Ford’s legacy—they draw constantly on knowledge from previous moments in history, as well as content from their debate and English courses. In this classroom, Mr. Worrell’s students are building their ability to make connections across historical periods, to draw on different sources of information, and to ask the tough questions that will help them form their own unique opinions about history.

That’s how their teacher is preparing them for not only college-level academic work, but also for the challenges—intellectual or otherwise—that their futures will throw at them.

Think Like Historians

Twelve years into his teaching career, the question of how to prepare students to be critical thinkers is still the one that drives Art Worrell every day.

To do that, Mr. Worrell spends the bulk of his class time putting texts—key primary and secondary sources for the time period, not arbitrary textbook passages—in front of his students, and asking them to investigate questions.

“It’s about giving them the tools to become socially aware, to have a certain level of consciousness about themselves, their own identity, this country, its history, the way it is, and what it could be,” he says. “In service of that, students need to be able to think and write like historians. When they get a document in front of them, they’re thinking about why this person is saying this thing, at this time, in this way.”

Students discuss Reagan's policies, citing evidence from primary source documents.

At the start of class, he’ll give them a central text and let them use it to formulate a hypothesis.

“It’s an inquiry-based model,” he says. “It starts with a question. They investigate and come to their own conclusions.”

Students also do almost all the talking in this class. That’s markedly different from many high school history classes, where lectures are at the center of the lesson.

Here, Mr. Worrell gives his students a short lecture only after they’ve already formed an initial hypothesis about the central text and question. The lecture provides context—and important content knowledge—but it’s only a tiny piece of the whole puzzle. After just fifteen or twenty minutes, Mr. Worrell passes the thinking and discussion back to his students.

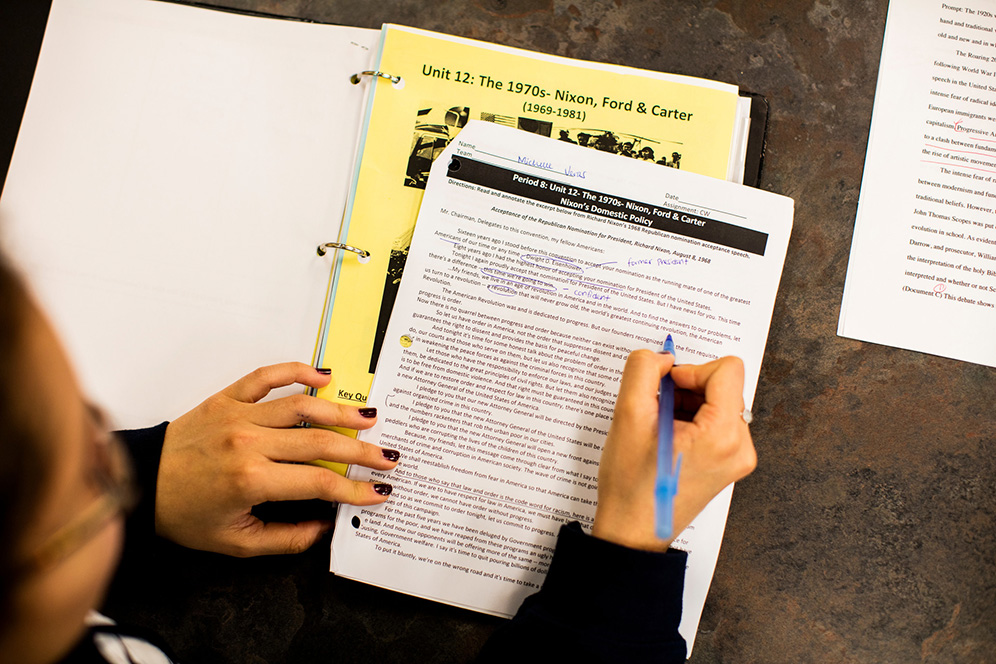

Michelle Veras annotates Nixon’s acceptance speech for the Republican presidential nomination.

And the bar for that thinking and discussion is high. It’s not enough to memorize facts—nor is it acceptable to take a single author’s, textbook’s, or even teacher’s perspective as truth. Instead, they’ll have to establish their own well-reasoned, evidence-based view of American history.

That’s what they do now with their central text for the day: Nixon’s acceptance speech for the Republican presidential nomination. Mr. Worrell asks them to consider what they can garner from the speech about Nixon’s vision for America.

At Shatavia and Michelle’s table, the girls pore over the speech, underlining and annotating as they go.

Shatavia points to a paragraph in which Nixon speaks of the courts “weakening the peace forces as against the criminal forces of this country.”

“I think he’s referring to the Warren Court,” Shatavia says to her group. “Because you know, they gave more rights to the accused. I could be wrong, but that’s what I think.”

“Yeah,” Michelle concurs. “Definitely. He talks about Supreme Court rulings. I just don’t know how he’s going to go and reverse those.”

The group turns to Nixon’s comments on private enterprise. Michelle taps her pen on the table. “He says, ‘Instead of Government jobs and Government housing and Government welfare, let Government use its tax and credit policies to enlist in this battle the greatest engine of progress ever developed in the history of man—American private enterprise.’”

She looks up at her group. “So what does that mean?”

Kristie Valentin makes an eloquent argument about the factors contributing to the rise of conservatism.

“I don’t know,” says Shatavia, contemplative. “I thought he was talking about big businesses.” Mr. Worrell pauses at their table. “So in terms of policy, what’s he calling for?” Without giving anything away, he pushes them to think beyond what’s on the page in front of them, to use their knowledge of economic policy to infer deeper meaning in Nixon’s words.

Shatavia considers the text. “Investing in these businesses.”

Michelle chimes in. “And less regulation on big businesses.”

“Okay. And where have we seen that before?”

“Laissez-faire,” Michelle suggests.

“The 1920s,” Shatavia adds. Mr. Worrell moves on, satisfied that his historians are putting together the pieces they’ll need to understand what happens next.

When the class comes together to discuss the text, they pay particular attention to the portion of Nixon’s speech where he posits that black Americans do not want government assistance.

“Anyone else think this part is kind of funny?” asks Mr. Worrell.

“It’s like he’s talking for black Americans,” says Himaayah Agwedicham, 17. “As if he knows what’s best for them. Except…he’s not black.”

As the class picks this apart, a debate emerges. Did Nixon’s ideas in fact align with the Black Nationalist movement? Michelle points to his comments about African Americans owning their own businesses as evidence. Or, rather, were they a manipulative attempt to use the language of equity to dismantle government programs that matter for low-income and minority Americans? Himaayah thinks so.

They don’t come to a conclusion by the end of the hour. But they do establish key questions they’ll investigate in the week to come. Tomorrow, they’ll look at more texts to deepen their understanding and, perhaps, shift their thinking—just like historians do.

It’s about giving them the tools to become critical thinkers, to be socially aware, to have a certain level of consciousness about themselves, their own identity, this country, its history, the way it is, and what it could be.

In service of that, students need to be able to think and write like historians.

– Art Worrell

The Freedom to Choose

Listening to the students’ confident command of history, it’s tempting to assume that their path through school has always been easy.

But for seniors Shatavia Knight, Himaayah Agwedicham, Kristie Valentin, and Michelle Veras, the challenging schoolwork they’re tackling here is not taken for granted. Each girl’s parents emigrated from a different country, and each cites education as a primary driver for their families’ moves.

“Coming to the U.S. from Ghana, my parents didn’t have that much money,” Himaayah explains. “They wanted to provide the best education they possibly could for their children. What they wanted for me was the freedom of choice. That’s something that’s very limited to people of color or people of low income—the freedom to choose what you want to do, rather than being forced to settle for things you have to do. They want me to be happy in terms of the options I have in life.”

What [my parents] wanted for me was the freedom of choice. That’s something that’s very limited to people of color or people of low income—the freedom to choose what you want to do, rather than being forced to settle for things you have to do.

– Himaaya Agwedicham, 17

Student Kristie Valentin at North Star College Preparatory High School.

Her classmates understand. Michelle says her mother, who emigrated from Ecuador, has “always had this American dream, but her American dream is not a house and a dog and a fence. It’s of higher education being accessible and attainable for her children. I’m fulfilling that dream.”

Kristie, also 17, comes from a family of women, she explains, and her mother and grandmother both had to sacrifice their own educations to care for their families.

“My mother was a straight-A student in high school, but her father prohibited her from going to college in order for her to get married to my father. She’s always instilled in us that you don’t have to give up something in order to be something else.”

At a lot of schools, they don’t care whether or not you do the work, or even if you come to class. Then you start noticing that these kids are also the kids who are not going to college.

– Kristie Valentin, 17

It’s clear they take their education—and the responsibility that comes with it—very seriously.

In a cluttered teacher workroom, they smile as they rattle off their college acceptances: For Shatavia, Middlebury, on a Posse scholarship; for Himaayah, Swarthmore, Lehigh, Princeton, and Cornell; for Kristie, Lehigh, Roger Williams, and Rowan; and for Michelle, Bowdoin, on a QuestBridge scholarship.

But each knows plenty of young people who have not had the same school experiences—and therefore the same opportunities to pursue their goals. The girls point to older siblings and friends in the neighborhood whose schools have not prepared them for long-term success.

“When you’re young, you think they have it easy,” says Kristie of friends from other schools. “At a lot of schools, they don’t care whether or not you do the work, or even if you come to class. Then you start noticing that these kids are also the kids who are not going to college.”

Mr. Worrell’s classroom showcases student work and celebrates students’ achievements.

Mr. Worrell sees his students grappling with those disparities. “They look at some of their friends who go to different schools, and they see opportunities closed to them for a variety of reasons,” he says. “It creates all sorts of interesting dynamics for them as they try to navigate those two worlds.”

That’s an experience he understands on a personal level.

“I grew up in the Bronx, which is not all that different from Newark,” he says. He first visited North Star when he was a senior at Rutgers. “I saw myself in a lot of these students. I saw a much more motivated, driven version of myself. I was inspired by them.”

I saw myself in a lot of these students. I was inspired by them.

– Art Worrell

Shatavia, the youngest daughter of a Trinidadian immigrant, says her education has left her better prepared to achieve her goals than her older siblings’ did before her. But even armed with a highly competitive, four-year college scholarship, Shatavia seems perhaps most proud of her role as Editor-in-Chief of Broad & Central, North Star’s literary magazine.

In her poetry and prose, she offers clear-eyed observations of her community, her neighbors, the people she rides the bus with and sees on the street corners. In a recent poem called “To the Nobodies,” she writes,

“I want my words to be a bomb that radiates,

To burn off the tumors of ignorance and hate that have infiltrated our minds like a cancer”

Evident in her emerging voice is her desire to be heard, to make a difference. That’s what her mother wants for her, more than anything, she says. Shatavia believes her experience in Mr. Worrell’s class is setting her up to do that.

“These challenging classes help me think more critically, make me a better writer, make me much more socially aware,” she says. “The things I’m learning in history help me want to be an agent for change, and a person who advocates for social equality.”

A Better Benchmark

To give his students every opportunity to stretch themselves to their fullest potential, Mr. Worrell is constantly raising the bar for them.

How high the bar should be, however, wasn’t always so clear. When Mr. Worrell taught middle school history, he thought he understood “rigor,” because it meant readiness for high school work. “When I got to the high school, I was sort of at a loss. We talked about college readiness, but I didn’t know what that meant, really.”

That’s exactly what the AP exam and the Common Core standards for literacy in history and social studies have helped him define.

The class shares feedback on a student's argument.

The Common Core’s social studies standards—often-overlooked reading and writing standards for social studies and history in grades 6-12—ask students to be able to do things like analyze primary and secondary texts (and note discrepancies between sources); integrate diverse sources of information; and evaluate an author’s premise or arguments and corroborate or challenge them using evidence from other sources.

In other words, kids should be able to read, write, and talk about history at a college level. “Our students can walk into a college classroom and not just exist, but almost drive a survey course in history,” says Mr. Worrell.

That expectation is the same for students in North Star’s non-AP history courses, too. The non-AP classes move at a slower pace, but the goal is the same: “They can write and discuss at a college level. That’s our benchmark.”

I didn’t know how we were going to define rigor. We talked about college readiness, but I didn’t know what that meant, really.

– Art Worrell

In retrospect, he now realizes that he wasn’t asking enough of his middle schoolers: The level of “high school work” he was preparing them for wasn’t high enough. If he were to go back in time, he says, he’d raise the bar and demand more of his students at an earlier age.

Figuring out how to hold his students to the right expectations, and then how to put challenging enough content in front of them to get them there, hasn’t been easy. But the payoff—for the kids—has been huge.

Ready to Learn

For Shatavia, Michelle, Kristie, and Himaayah, the challenges in Mr. Worrell’s class—and across their school experience—have prepared them to approach the next phase of their lives with the grace and confidence of young people who know who they are and what they’re capable of.

“We’re in a mindset of coming to class ready to learn, and we’re able to think deeply about our opinions,” says Kristie.

Michelle concurs. For her, working hard in school is about getting back what she puts in. “I know if I’m not prepared, I’m not going to be able to engage in the discussion. It’s not even about getting the work done. It’s about what you take out of that, that’s really so gratifying.”

And it’s not just the challenging academic content that has prepared them so well. (Although the girls have cited Sojourner Truth, bell hooks, Malcolm X, and Assata Shakur in the span of ten minutes, and Shatavia notes that her English grade has gone up thanks to all the knowledge she’s gaining in history—so the academics are nothing to sniff at.) But they’ve also benefitted from the positive community at their school.

“It’s a culture of home, and a culture of acceptance,” Himaayah says. “And feeling like you could mess up without feeling like people are against you.”

Their teacher’s hard work and commitment to their long-term success, not to mention his pure love for history, has not gone unnoticed.

“I see his passion for history,” Himaayah adds. “It makes me want to learn more. I could have a teacher who is teaching out of a textbook. Instead, I have Mr. Worrell.”

I really don’t feel like anything’s too hard for me. The experience I’ve had of being pushed constantly, of being asked to dig deep, or being asked to learn seemingly impossible things—those things have made me realize that I can do just about anything I put my mind to.

– Shatavia Knight, 18

As far as Shatavia is concerned, she is now prepared to make her own history.

“I really don’t feel like anything’s too hard for me,” she says. “The experience I’ve had of being pushed constantly, of being asked to dig deep, or being asked to learn seemingly impossible things—those things have made me realize that I can do just about anything I put my mind to.”

So what does she plan to put her mind to, to become that “change agent” she aspires to be?

“I want to be a teacher.”

Read Another Student's Story

Stay in the Know

Sign up for updates on our latest research, insights, and high-impact work.

"*" indicates required fields