Publication: Room to Run

Knowledge Matters

Abril’s Class | 2nd Grade at Westergard Elementary School in Reno, NV

Abril Cobian-Luna, Lydia Burton, and Grace Stapleton are discussing heroes of the Civil War.

They’re getting started on a document-based question (DBQ), which asks them to use their prior knowledge and a set of texts and images to rank five Civil War-era leaders in order of heroism. Once they’ve made their rankings, they’ll be asked to provide evidence for their top three in an essay.

Though they’ve only just gotten started, the girls already have a hunch about the two most heroic leaders on the list: Harriet Tubman and Clara Barton. Why? Both exhibited bravery, they explain with certainty.

If you remember this kind of exercise from your high school days, it’s because DBQs are a mainstay of AP history courses. This one is no different.

Except Abril and her classmates aren’t in high school. They’re in second grade.

Learning Isn’t Cute

In Chris Hayes’ second-grade classroom at Westergard Elementary School in Reno, Nevada, this is how her students will finish off their unit on the Civil War—synthesizing their knowledge, forming opinions based on evidence, and writing and talking about it.

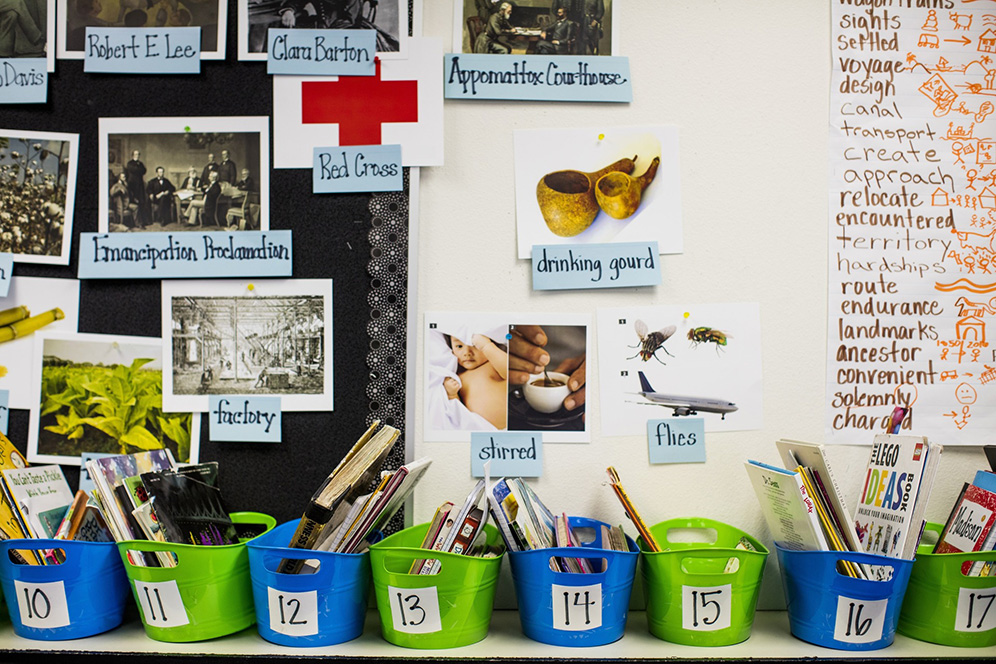

Content-specific vocabulary is everywhere in Mrs. Hayes’ classroom.

Here’s the assignment this group of second graders will tackle: “A hero is a person who is admired for courage and achievements that help others. Using evidence found in the following documents, your knowledge of our readings, and at least four of the vocabulary words above, rank all of these people in order from least heroic to most heroic. Then, write about your top three most heroic choices. Make sure to use details to support your reasoning for why these people are heroic.”

The seven-page packet in front of her students today includes photographs and passages about Abraham Lincoln, Harriet Tubman, Robert E. Lee, Clara Barton, and Ulysses S. Grant. The vocabulary words at the top of the first page include “Confederacy,” “abolitionist,” and “emancipation,” among others.

Around the room, quiet but thoughtful conversations about the first document in the packet are taking place. Abril, Lydia, and Grace are nestled amongst pillows on the rug, huddled over their clipboards. At a nearby table, Madison Brenner and Alyson Burke are parsing out the finer points of Abraham Lincoln’s debates with Stephen Douglas.

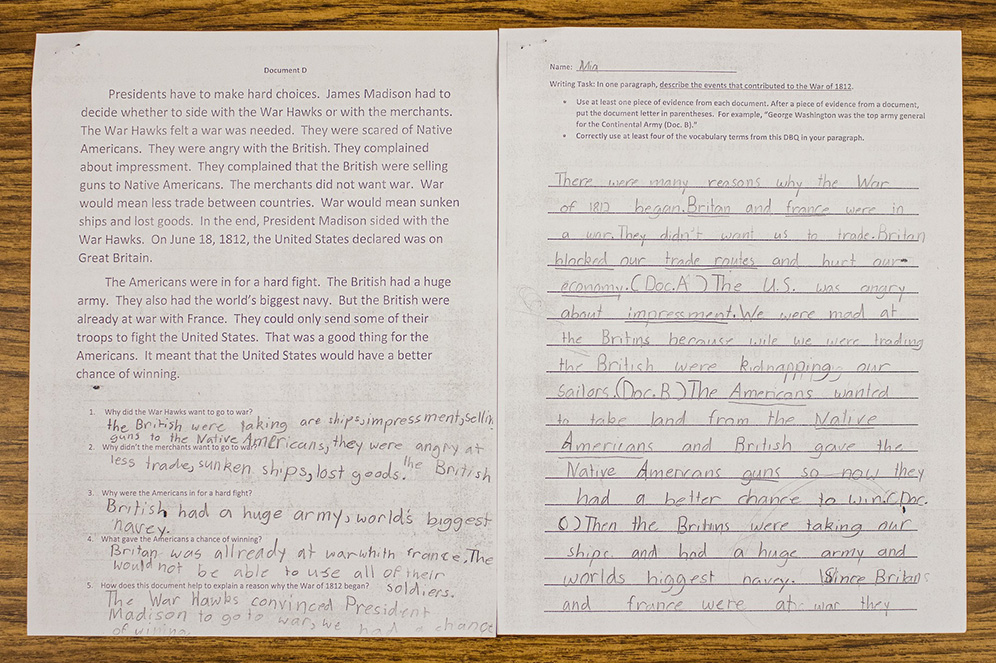

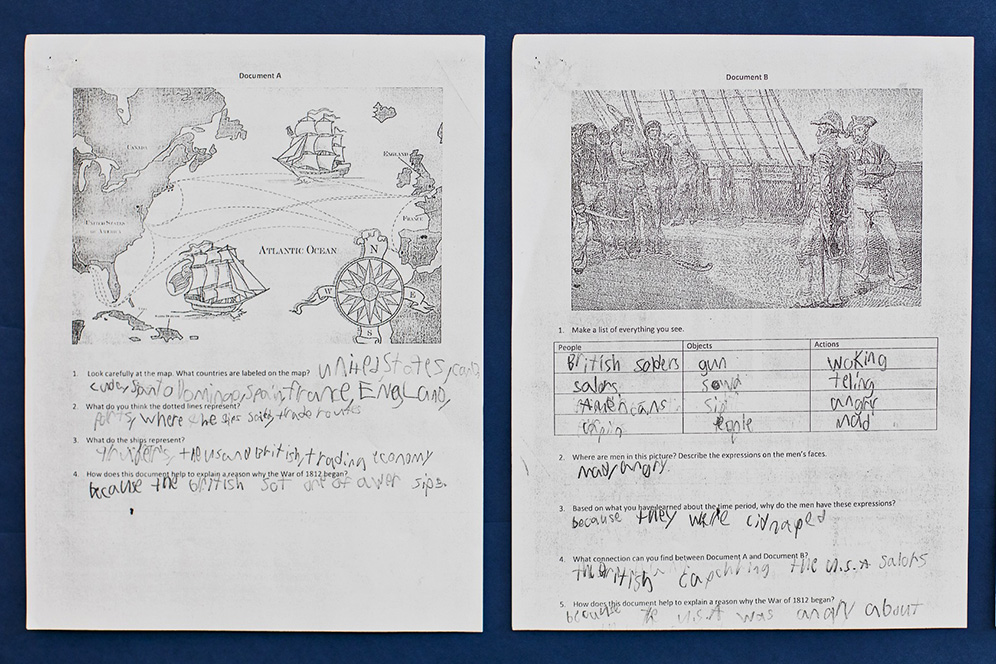

A second-grader's document-based question on the War of 1812.

“Explain what Lincoln meant when he said, ‘A house divided against itself cannot stand,’” Madison reads from her packet. The girls reread the text silently, underlining in pencil as they go.

“So,” Madison, 8, posits, “that means, if everyone’s arguing, the country will break apart.”

Most of us probably wouldn’t overhear these conversations or read this assignment and peg them for second grade. But Mrs. Hayes’ Civil War unit is part of Core Knowledge, a literacy curriculum aligned to the Common Core State Standards. In Core Knowledge, students build reading, writing, speaking, and listening skills through units that center on social studies topics like westward expansion, the War of 1812, and ancient Asian civilizations, and science topics like the human body and insects. Students are becoming literate, in other words, while also becoming informed—and vice versa.

Mrs. Hayes believes that if most of us don’t think second graders can do this level of work, it’s because we rarely ask them to try.

Mrs. Hayes reminds her students that their content knowledge will help them read and write about the Civil War.

“We hear kids this age having complex conversations with each other, and our reaction is that it’s cute. But it isn’t cute. It’s what we should expect them to do,” Mrs. Hayes says. “The kids are engaged. They think learning is fun. But I don’t teach this way because it’s fun. That makes it too simple. What we’re doing for them is very important.”

It’s important not just because these second graders are building critical content knowledge that helps them become stronger readers, writers, listeners, and speakers (and that will be built upon in higher grades). It’s also important because in asking her students to do so much active thinking and engaging on these topics, Chris Hayes is laying the foundation for her students to persevere through more challenging work in the years to come. She is building students who own their learning.

Challenging Content Is a Civil Right

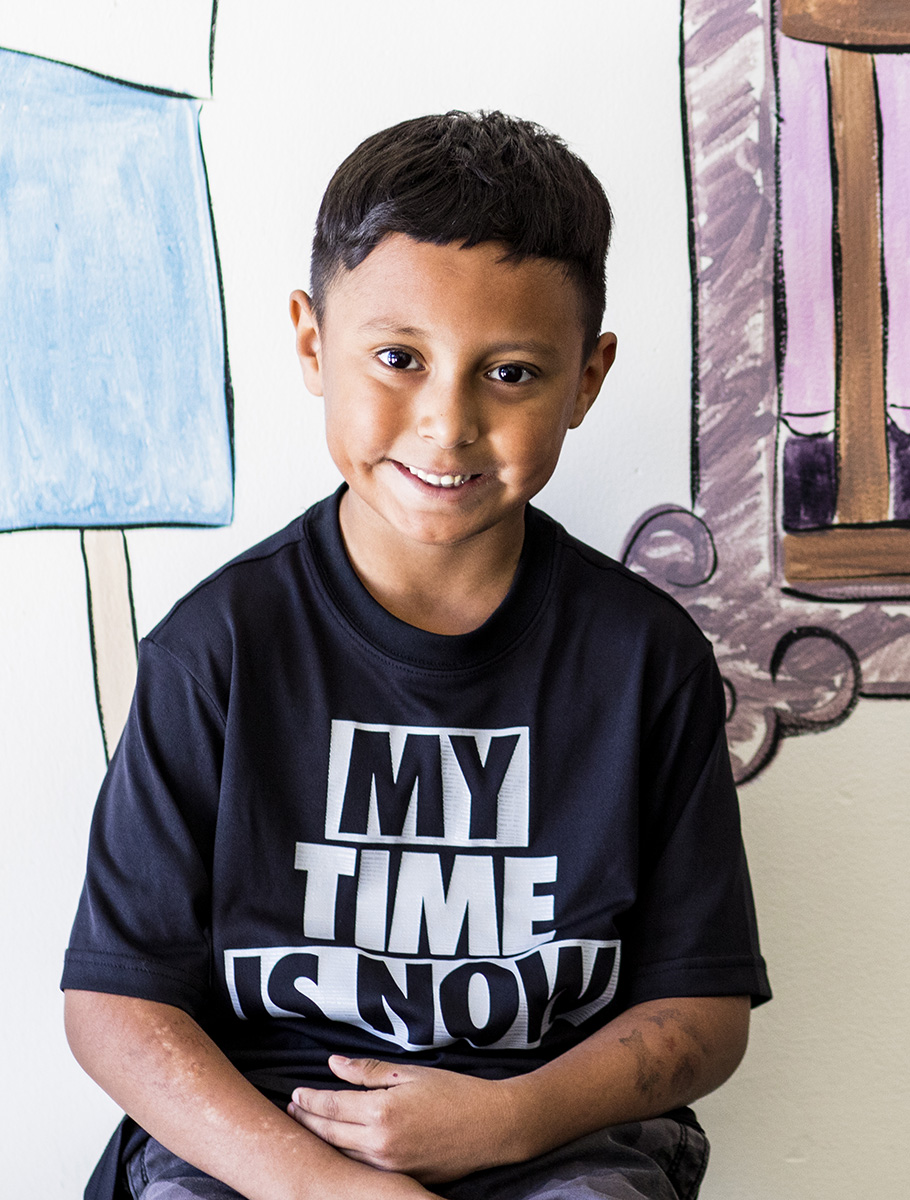

Abril, 7, is one of those learners.

A few weeks before Mrs. Hayes’ class even gets to the DBQ, they’re already building their knowledge of the Civil War. As the class gathers on the rug to hear a story about Ulysses S. Grant, Abril positions herself right in front.

Soft-spoken and pensive, Abril speaks Spanish at home and struggles with reading; writing and math both come more easily to her. Nonetheless, come time for the Civil War read-aloud, Abril’s eyes are glued on her teacher, ready to listen. When Mrs. Hayes pauses and asks the class to discuss a question related to the story, Abril eagerly turns to her partner to participate.

Abril Cobian-Luna at Westergard Elementary School.

It’s the first time they’ve heard of Grant. But they already have a lot of context and related vocabulary to support their understanding, so no one panics when a few minutes later, Mrs. Hayes sends them back to their tables to write—completely unstructured—about Grant in their Civil War notebooks.

Abril scribbles away, describing Grant as a “civil war general” who was “a really brave man.” Though she hasn’t heard of Grant before today, she explains that she knows about him from “listening to the story.”

Listening and learning is fun.

– Abril Cobian-Luna, 7

Is it a lot to ask a seven-year-old who is still building her English skills to listen to new information about American history, talk about it with her classmates, and write independently about it?

Sure, says Mrs. Hayes. But that’s the point, and Abril’s not fazed. It’s something she and her classmates do often, and she likes learning from stories. “It tells me what’s going on. Listening and learning is fun,” Abril says quietly, before returning to her paper.

Across the table from Abril, her classmate Mia McDowell, 8, has written almost twice as much, and she’s lobbing follow-up questions at Mrs. Hayes.

“When did Ulysses S. Grant die?”

Mrs. Hayes demurs, saying Mia will have to wait to find out.

“Well, when was he born?”

Here, Mrs. Hayes pauses. She doesn’t know offhand.

“We’ll have to look it up,” she tells Mia, who nods, satisfied.

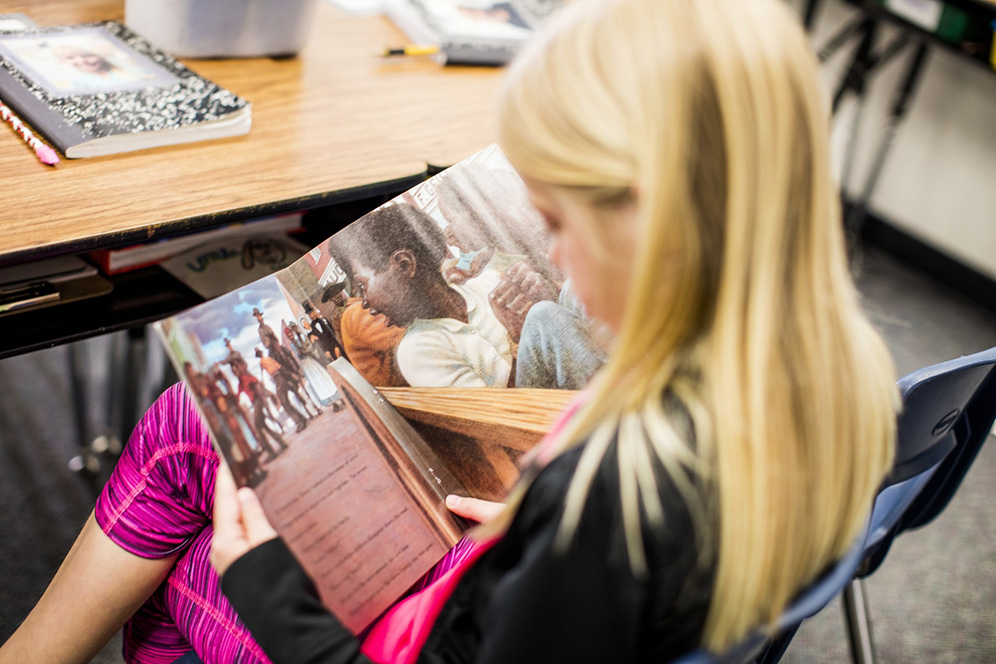

Mia McDowell reads about the Civil War.

Mia and Abril are accessing today’s lesson at different levels. Mia, who joined Westergard from a local parochial school and isn’t shy about telling everyone how much of a better education she’s getting in Mrs. Hayes’ class, is galloping ahead, analyzing the text, shooting her hand up to answer every question, and writing in complex sentences. Abril’s grasp, for now, is more surface-level. Still, from Mrs. Hayes’ perspective, both girls are getting something critically important out of this approach to literacy instruction: They’re building knowledge while they develop their reading, writing, speaking, and listening skills—and the knowledge, in turn, is helping them deepen those literacy skills.

“Some people think it’s not appropriate for our English language learners or students with any kind of learning challenges to do this work. They think it goes over their heads,” says Mrs. Hayes.

“To me, it’s a civil rights issue. Who are you to decide what they can and can’t access? If I withhold the Civil War from Abril, the other kids are going to pass her by. I need to help her with her reading skills, but she has to have knowledge too, so that when she catches up with her reading, she’ll be right there with the rest of the kids. If, year after year, we don’t expose them to this level of work, we’re making the problem worse.”

The read-aloud portion of Mrs. Hayes’ lesson is critical for that. Research shows that students, especially in the early years, are able to access much more complex ideas through listening than reading. So when Abril listens to that story on Grant, she’s processing more complex syntax, vocabulary, and ideas than she would get from a text she’s currently able to read independently. And listening comprehension supports reading comprehension—so if students don’t get exposure to challenging texts read aloud to them, it’s harder for them to move ahead with their reading.

“If Abril lived in the books we’re reading together, it’s Pat’s favorite cat,” Mrs. Hayes explains. “There’s no discussion there. There’s no deeper level questioning. She needs to be exposed to that questioning, that discussion, which cannot be done with the text she’s able to access on her own right now.”

That doesn’t mean students aren’t still spending time reading books “on their level”—meaning at the level they can decode independently. They do, every morning. And students who need reading support still get it, in the form of phonics and one-on-one instruction. But now that is just one piece of their literacy instruction, not the whole thing.

To me, it’s a civil rights issue. Who are you to decide what they can and can’t access? If, year after year, we don’t expose them to this level of work, we’re making the problem worse.

– Chris Hayes

Mrs. Hayes believes this content-rich approach to literacy instruction means all her kids are getting access to not just content knowledge, but also the critical thinking skills that come along with it, which will serve them well in the years to come.

“I ran into a teacher from a very affluent school with excellent test scores,” she explains. “She asked me about Core Knowledge, and I was telling her how my students had gotten into this amazing debate about slaves shooting their owners to get away. And she said, ‘Oh, my kids do the same thing. We read The Three Little Pigs and we talked about who was right, the wolf or the pigs.’”

Mrs. Hayes pauses, frustrated even by the memory.

“It’s totally not the same thing. We are giving them knowledge, and it’s very powerful. When they are really and truly supposed to attach themselves to this information, they will be ready.”

Kids Need to Learn Stuff

Chris Hayes has been teaching for twenty-two years, all over Washoe County. She learned to teach elementary school by giving students information, teacher-to-student: in math, formulas; in literacy, discrete reading and writing skills. In social studies and science, not much of anything.

“Everyone was just picking topics they were interested in,” Mrs. Hayes says. “A unit on pumpkins; a unit on butterflies. There was no cohesiveness to it.”

Today, Mrs. Hayes is an unapologetic advocate for the Common Core standards. She believes the transition to the standards, which Nevada adopted in 2010, has dramatically improved her teaching, and she’s seeing dramatically stronger learning from her students as a result.

“I taught for twenty years before someone said, ‘Hey, we need to be teaching them stuff,’” says Mrs. Hayes. “We were teaching them content, but in isolation. It was very superficial, especially in K-2. The expectations were just way too low.”

Mrs. Hayes’ students use evidence from texts and visuals to answer questions.

Mrs. Hayes’ higher expectations are paying off by any measure. Her students have an average reading score of 191 on the Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) tests, the benchmark assessments used by Washoe County, compared to an average of 178 for the district. Nationally, average growth on the MAP reading assessment is about 13 points per year; this year, Mrs. Hayes’ students grew an average of 11 points in just one term.

That’s not the result of test prep, though; she doesn’t do any. “They are more prepared for any testing situation than ever before because I’m asking them to do more complex things in class. But it’s not to prepare them for a test.”

She thinks her students also succeed in testing situations because they’re used to being challenged. When faced with a tricky passage on a MAP test—or with a challenging text in any context—Mrs. Hayes says her kids “sit there and try. Because they know I expect them to try. They don’t give up. That’s the expectation.”

They are more prepared for any testing situation than ever before because I’m asking them to do more complex things in class. But it’s not to prepare them for a test.

– Chris Hayes

Mrs. Hayes looks on as students work independently.

To listen to Mrs. Hayes talk about how her instruction has shifted as a result of the new standards, it’s hard not to think this is common sense. But the transition to the new standards has been met with tremendous resistance.

In part, Mrs. Hayes thinks professional development for teachers has over-focused on particular skills—the how of teaching to the Common Core standards—and less on the why. She believes changing that would address some of the resistance to the standards she sees among her peers.

“A lot of teachers have been down this road before. The new book is the answer. This is the answer. I think they’re just cautious. Professional development needs to be about why this is so important, why it’s important to build knowledge and vocabulary.”

As for learning how to do it, Mrs. Hayes posits that the content itself might be even more important. “I would rather my own child sit in a class with a not-so-great teacher listening to great content, than an excellent teacher doing a pumpkin unit. I think the content is more important than the delivery.”

She laughs. “That’s not a popular opinion.”

Whether it’s the content or the delivery—or most likely a combination of the two—it’s hard to argue with Mrs. Hayes’ results. It’s even harder to argue with the happy, engaged faces of the children in her classroom.

Nobody’s Crying

Brandon Galvan, 8, has one of those happy faces. An amicable kid with a big grin, Brandon has been inspired by the challenging content in Mrs. Hayes’ classroom, according to his mother, Kelly Galvan.

Ms. Galvan says the challenging content in second grade has pushed her son far beyond what he knew he was capable of—and beyond what she’d seen in him before.

These days, Brandon comes home excited to tell his family what he’s learning. “It’s comforting as a parent to know that he loves school and he’s getting a great experience,” says Ms. Galvan. According to his mom, the challenging content has helped Brandon become a more eager and independent learner.

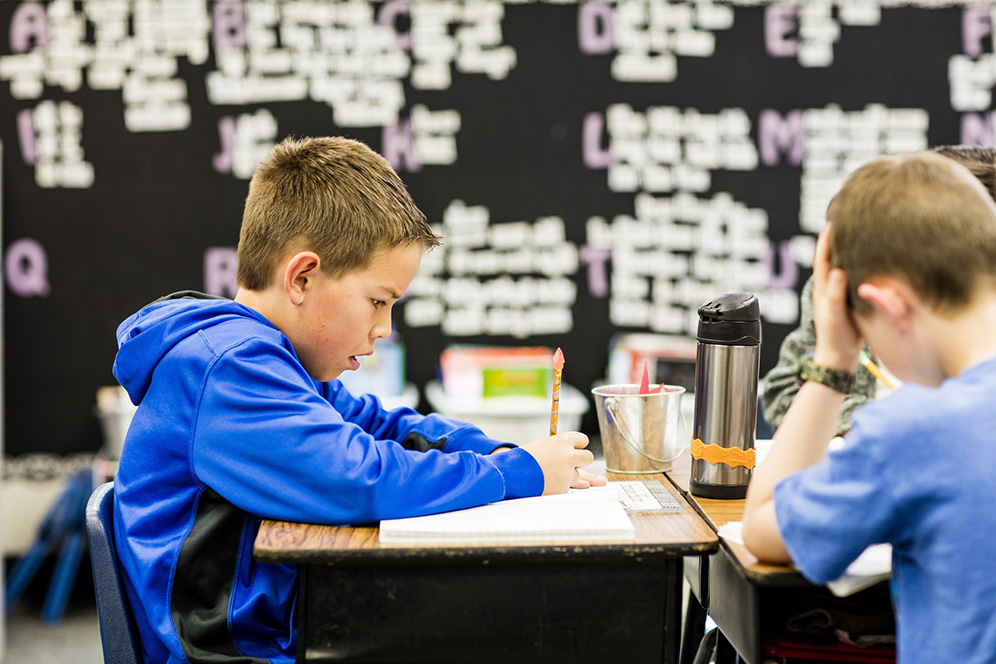

Brandon writes about heroes of the Civil War for his document-based question.

Brandon’s older brother went through Westergard before the school adopted Core Knowledge, and his experience was notably different. “We had some less challenging years,” says Ms. Galvan. “That hasn’t been the case at all with Brandon this year.”

Today, Brandon and his tablemate, Lena Nouwakpo, are busily writing about Grant, who they agree is a pretty cool guy. Both say they love reading and writing stories—and it’s clear that they’re getting hooked on history, and knowledge-building more broadly, through reading and writing in this classroom.

“I like challenging stuff,” Brandon says. “If I’m not good at it, I want to practice more and get good at it.”

Brandon Galvan is more excited about school than ever before.

From Mrs. Hayes’ perspective, that’s exactly the point of stretching her kids: It gets them excited about what they’re capable of. That’s not a position everyone agrees with.

“There is a strong belief that if we give them things that are too hard for them, we’ll frustrate them, shut them down,” says Mrs. Hayes. “They will quit school, go home, and cry. They don’t, obviously. Nobody’s crying. Everybody’s happy doing this work, and I’m supporting them.”

The point is putting the work in front of them and seeing what happens, she says—not necessarily holding fast to a particular, pre-determined bar. “I give it to them and just see what they can do with it.”

I like challenging stuff. If I’m not good at it, I want to practice more and get good at it.

– Brandon Galvan, 8

Despite twenty-two years of teaching, Mrs. Hayes says she’s still learning as she goes. “Because it’s new, I’m not quite sure of the expectation. How appropriate is it to expect seven-year-olds to reason? I don’t know yet. I push for it, but not everyone can do it yet.”

Still, she says, that’s not a good reason to keep them from trying.

“Everyone can write to this topic. Everyone can say, ‘This is why the War of 1812 began.’ Or, ‘This is why he or she is my hero from the Civil War.’ Everyone can do that, no matter what level.”

What Makes a Hero?

As the class wraps up their unit on the Civil War, they run into a complex question. Can Robert E. Lee be considered a hero?

Mrs. Hayes asks them to offer some evidence in support of their positions. A heated debate ensues.

Griffin Muckel, 8, sees room for gray area. “He’s sort of a hero, because he did fight for slavery, and he fought in the Mexican-American War.”

Mrs. Hayes’ students debate whether or not Robert E. Lee can be considered a hero.

Grace, also 8, draws a harder line. “Now that’s why he’s not a hero,” she says. “Because I don’t want slavery.”

“But maybe he didn’t want slavery—maybe he just didn’t want to go against his own state,” a classmate considers.

The discussion spills over into music time, and Mrs. Hayes has to cut them off to get them out the door. “Who’s feeling a little conflicted about this?” she asks, and the kids nod.

Grace Stapleton shares an idea with her classmates.

By the end of the week, they’ve hashed out their lists of heroes. Brandon, for his part, chooses Clara Barton, Abraham Lincoln, and Harriet Tubman as his top three. In his essay, he cites Barton’s founding of the Red Cross and notes that she once took a bullet through her sleeve and kept on working.

Abril, too, puts Barton on the top of her list. “She wanted to save the people from dying,” Abril writes in her final essay. “And she was not scared.”

For these second graders, fearlessness seems to impress more than anything else. And as they dive headlong into learning new content, debating with their classmates, and expressing their ideas in writing, it’s clear there’s not much they’re afraid of, either.

Read Another Student's Story

Stay in the Know

Sign up for updates on our latest research, insights, and high-impact work.

"*" indicates required fields