Initial Efforts Prove Successful

To overcome this challenge, Leading Innovation for Tennessee Education (LIFT), a network of Tennessee school districts in both urban and rural areas, came together and partnered with TNTP in addressing this important issue. TNTP worked side by side with district leaders to set a clear vision and strategy, introduce strong English language arts (ELA) curricula, and build the capacity of teachers and leaders to change the literacy experience for students.

These districts saw results and became an example for others in the state. In 2019, 67 percent of districts in the network increased the number of third-grade students scoring at least “on track” on Tennessee’s ELA test.

That same year, school districts that were part of the LIFT network each had at least one school that exceeded academic growth expectations, and 20 schools across the network were named “reward schools” by the state. Reward schools demonstrate high levels of performance and/or improvement in performance by meeting annual measurable objectives across performance indicators and student groups.

Policy to Improve Literacy

Building upon this momentum, in 2021 the Tennessee Department of Education initiated the landmark Literacy Success Act that provided both incentives and support for districts, schools, teachers, and families to improve literacy across the state with a particular focus on early literacy.

For teachers to effectively implement a systematic, explicit phonics curriculum, they first need background knowledge in the brain science behind reading acquisition.

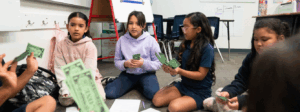

As part of that initiative, TNTP provided early literacy training; to date, more than 13,000 teachers across the state have completed this two-part course. These trainings included an online, asynchronous course and in-person trainings focused on the research and science behind how students learn to decode words while learning their meaning.

TNTP’s unique approach acknowledges that, for teachers to effectively implement a systematic, explicit phonics curriculum, they first need background knowledge in the brain science behind reading acquisition.

The biggest priority was to stay focused on concrete classroom practice.

- What do these evidence-based practices look like in a classroom of 6-year-olds?

- What does a strong phonics lesson look and sound like?

- How do I support a student who can decode but struggles with fluency?

Having a solution for these types of questions was critical. The focus on practical application meant that teachers left this training with more knowledge and, importantly, as skilled practitioners, ready to incorporate these new methods into the classroom.