“My parents came here to America for my education. It’s very important for me,” says Hajima, a 12th grader in one of the districts we studied for our recent report, The Opportunity Myth. She chose her high school specifically to meet her career goals. “I came here because of the new medical program and what they had to offer me.”

She’s part of a specialized medical careers track, intended to prepare students to work immediately after high school in a hospital setting while simultaneously earning college credit.

Hajima intends to be the first person in her family to go to college. Her family came to the United States as refugees in 2005. Her older siblings struggled academically in America, in part, Hajima explains, because of the language barrier. But she was younger when the family resettled, and adjusted well. She enjoyed school. Her father wants her to go to college so she can avoid the kind of suffering he’s experienced working in a local factory.

That’s her plan, too. “I’m hoping to be a neurologist.”

When she arrived at her new high school, Hajima’s hope was that the medical careers program would put her on the right path for medical school, both in terms of academic readiness and with some college credit already under her belt. In fact, she had transferred from another public high school—one with higher test scores and more advanced course offerings—explicitly because she’d been enticed by the promise of this program.

Considering that Hajima joined her new school based on the promise that it would prepare her for pre-med studies in college, she was shocked to learn upon arrival that there were no AP math or science courses available to her.

She maxed out on the school’s math offerings as a junior. “They only have up to pre-calc,” she says. “I took that last year. If we feel the classes they have aren’t challenging for us, there are no other options.”

She’d jump at the opportunity to learn more. “We want to be more prepared,” she says.

When Hajima and her best friend talk about how it feels to sit in classes that aren’t challenging enough, they speak of watching the clock. “The time goes super slow,” Hajima’s friend explains. In their physics class, for example, they might get through all the content in the first 20 minutes—and then have nothing to do. It worries Hajima deeply when she considers her future.

“I don’t want to feel like I’m behind when I walk into a class on the first day of college,” she says. “The teacher is not going to wait for me. I’m just going to be a small number in a class, and I don’t want to feel behind or left out.”

***

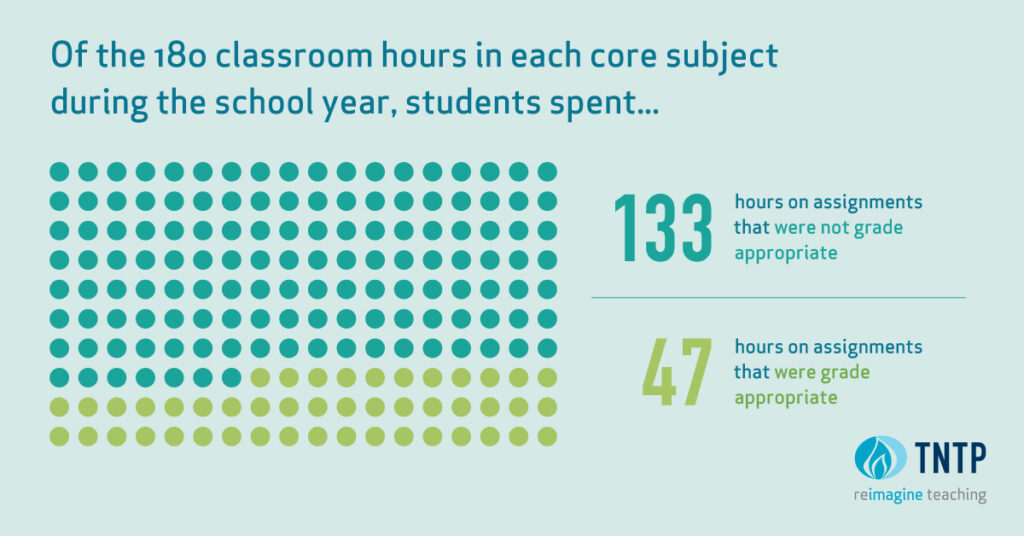

Hajima and her classmates will never get their time back—and it adds up. Across the five school systems we studied in The Opportunity Myth, we found that an average student spent almost three-quarters of their time in the four core subjects (ELA, math, science, and social studies) on assignments that were not grade-appropriate. In a single school year, that’s the equivalent of more than six months of learning time.

We met eighth graders in an ELA classroom who were asked to fill in missing vowels in a vocabulary worksheet, and students in an AP physics classroom who spent an entire class period making a vocabulary poster. These sound like extreme examples, but they were far more the norm than the exception. When students are consistently forced to do work below their grade level, they’re missing opportunities to learn and practice the skills they’ll need to make their life goals achievable. But they’re also being denied a chance to prove—to themselves as much as anyone else—what they are capable of.

When students are given that chance, they succeed more often than not: in the districts we studied, students met the bar on grade-level work they were assigned more than half the time. That’s true for students across all demographic groups, including students of color, from low-income backgrounds, with IEPs, who are learning English.

The problem is that far too few students get regular opportunities to do grade-appropriate work—especially students of color. We found that classrooms with more than 50 percent white students had 53 percent more grade-appropriate assignments, while classrooms serving more than 75 percent students from higher-income backgrounds had more than twice as many. Almost 40 percent of classrooms we studied with a majority of students of color never received a single grade-level assignment.

In other words, students like Hajima, who seek challenge and have generally excelled at whatever is put in front of them, are less likely to have opportunities that will ready them to meet their academic goals—not because they’re not able to do the work, but because they are Black, or Latinx, or come from low-income families.

***

Greater access to grade-appropriate assignments is an urgent priority for all students, no matter what their race, income level, or current performance level. This would raise the floor for all students’ experiences—and for students of color and those from low-income families, it could be one of the keys to closing academic gaps with their peers. We found that classrooms with students who tended to start behind that worked on grade-level assignments, on average, even 50 percent of the time gained seven months of learning in a single year.

What can education leaders do to ensure Hajima and students across the country spend their time in school on work that’s worthy of their goals? The first step is assessing how the assignments students are currently working on stack up. How much time are students spending on grade-appropriate content? After that gut check, stakeholders should make sure that teachers are using high-quality, aligned instructional materials on a daily basis. But we cannot leave teachers to sink or swim; helping students with vastly different needs, some of whom may be several grade levels behind, to succeed with grade-level materials requires a lot of experience and skill. So we must provide teachers materials-based professional learning to ensure that teachers know the value in grade-appropriate assignments and how to use them well.

Read and share The Opportunity Myth—then take the first step by requesting your own free action guide featuring tools and advice to help more students in your community have worthwhile experiences in school.