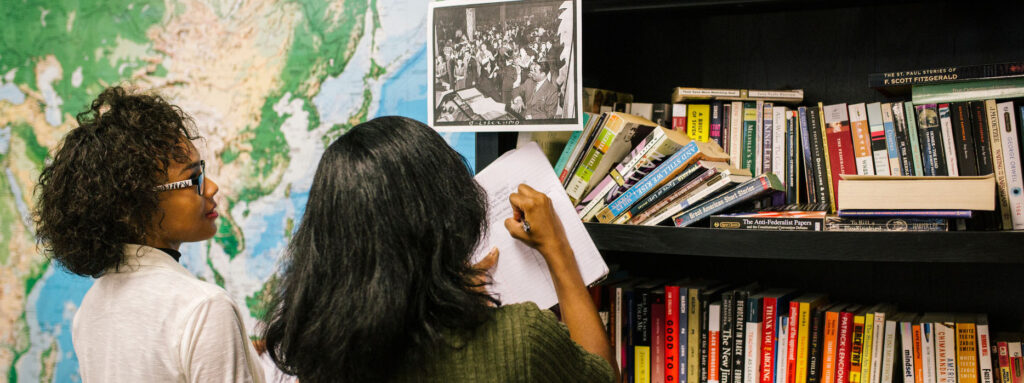

Bringing Black history into the classroom year-round is about more than learning facts and stories; it’s about questioning those stories—and understanding how they have been rewritten. The students in Brett Noble's English class do this every day as they study the literature and living history in their own backyard.

Eastern North Carolina is as rich in history as it is in peanut, cotton, and tobacco fields. Halifax County is one of the most economically distressed counties in the state. It’s also one of a few counties in North Carolina that maintains a vestige of the Jim Crow era: Despite the total student population in the county declining to under 7,000 in 2017, there are three superintendents, three school boards, three central offices, and three racially disparate and inadequately resourced school systems. It’s not uncommon for students to be zoned for schools far from their neighborhoods to maintain de facto segregation.

In 2015, the two predominantly black districts ranked last in our state in achievement. Suspension rates are up to eight times higher in those schools, and dropout rates are similarly disproportionate. Located on a peanut field across the Roanoke River in Northampton County, KIPP ENC Public Schools adds yet another layer of complexity, drawing students from several counties, including some who commute almost two hours in each direction to attend our school.

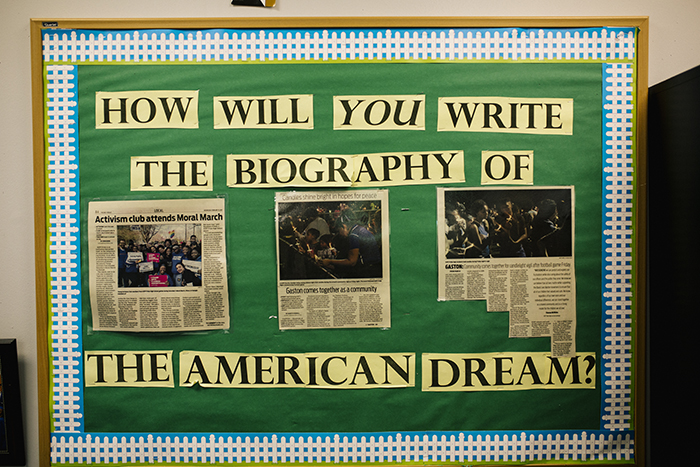

This socioeconomic landscape is in many ways another challenging text that my students are constantly reading—and living. For decades, the Halifax County NAACP and UNC’s Center for Civil Rights have sued for students’ constitutional rights to a sound, basic education. Earlier in the year, our class closely read a recent legal briefing and invited the Halifax County NAACP president himself to speak to the disparities and its effects on our community. They’ve learned that while the confederate flags they pass by on the way to school play a factor, so too does the method of tax distribution, with millions of public dollars distributed unequally among the three systems. When it comes to studying the biography of the American Dream in all of its moral, socioeconomic, and literary complexity, my students have to look no further than out the bus window.

When I think about relevance in the classroom, especially in the face of education networks working to write one curriculum for teachers across the country, I can’t help but think that the most local issues are the ones we must keep sight of. After all, it was Halifax County native and civil rights hero Ella Baker who said that “in order to see where we are going, we not only must remember where we have been, but we must understand where we have been.” Connecting curriculum to local places and issues is a necessary part of our work.

Read more about Brett's classroom in his essay, “Rooted in Place: Teaching Students to Look Ahead by Reflecting Back.”