Sarah Thomas teaches fourth grade at McMeen Elementary in Denver, Colorado. Denver Public Schools is a leader in their approach to district-led family and community engagement: their Parent Teacher Home Visit Program is in 79 schools and on a path to complete 10,000 visits this year. At TNTP, we believe home visits, and other acts of authentic community engagement, are critical to building supportive learning environments and helping kids see real academic growth. Sarah has been making home visits for three years. We asked her to share her experience building a successful relationship with one particular student and his family.

If you were to ask me what my favorite part of teaching is, my answer might surprise you: home visits. Heart to hearts with my favorite human beings, and their loved ones, over freshly steamed tamales? Yes, please.

But home visits are more than that. They allow me to strengthen the connections between the three most important forces in a student’s education life—the student, their family, and their teacher. When done right, they can be a powerful tool for improving students’ experiences in school. Case in point: my student Joel.

Joel is the son of two hard-working parents who emigrated from Mexico. His dad works on a construction crew in the mountains; he’s gone during the week and returns on weekends. His mother stays home taking care of his siblings. Before making my visit to Joel’s home last year, I’d been in touch with his mom and we had a chance to meet in-person at a parent-teacher conference. But the hurried twenty-minute conversation never moved past the basics of grades and homework, thanks to a long line of parents waiting behind her.

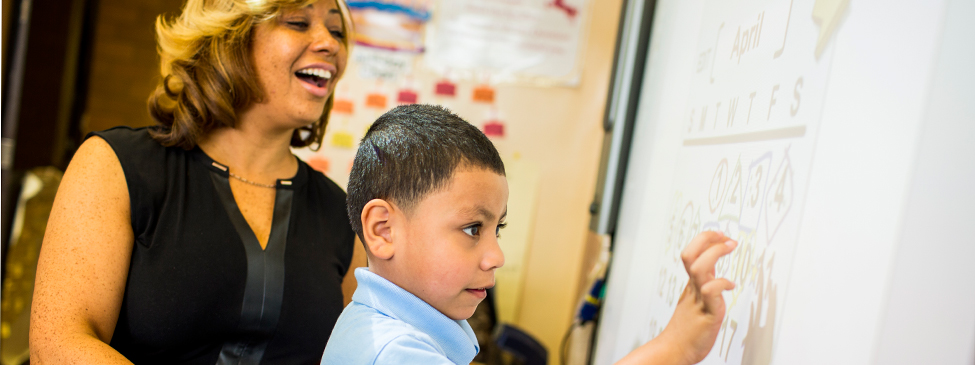

When the year started, I knew Joel was a capable student. It was obvious he was highly intelligent—he could compute equations in his head that took most students a while to dissect—but he struggled to find the motivation to give school his best effort. Though I consider myself someone who can connect with students on a personal level, Joel’s reserved demeanor left me at a loss.

When I walked through Joel’s front door, I was greeted warmly by his parents and his toddler brother, but Joel lingered behind a door, surveying the scene. I knew inserting him directly into the conversation wouldn’t help build his trust, so I spent time getting to know his parents.

As Joel’s parents told me about their family, they playfully cajoled Joel. I watched how he opened up in those moments. In my classroom, I’d been worried about pushing Joel by joking with him, but his interactions with his parents revealed he responded warmly to gentle teasing. Similarly, I’d been cautious about asking Joel to engage with his classmates due to his shyness, but watching him demonstrate immense care, patience, and initiative with his younger brother as they played on the floor made me realize he could thrive with the same responsibility at school.

After a couple of hours of conversation over pizza, I left Joel’s home excited by everything I’d learned and ready to use this new information in class: I began interacting with him more playfully, and during partner work, I paired him with a classmate who needed a lot of patience and encouragement. But even so, I didn’t fully comprehend how much of a difference my visit would make until the weeks and months that followed.

In class, Joel’s engagement skyrocketed. He’d always demonstrated talent in math, but began excelling far beyond where he’d been. His writing also improved dramatically, which I credit to the increased collaboration with his mom: When Joel put a lot of effort into a writing assignment, I took a picture and texted it to her so she could celebrate him at home—something I wouldn’t have felt comfortable doing before the visit.

At their core, home visits are all about empowering teachers—and families—to tailor learning experiences in ways that support kids’ individual needs. Spending time in a space where Joel felt most comfortable allowed me to notice things about him that I couldn’t see in a classroom setting, where he was much more guarded.

Likewise, when his family, whose native language isn’t English, shared their perspectives from the comfort of their home—with me as a guest instead of the other way around, in my classroom—it leveled the playing field between us. It also gave Joel the opportunity to see his family as vital sources of knowledge, and validate his native culture. A twenty minute conference could never accomplish this.

This year, I’m teaching Joel for a second year in a row. There is still so much to learn about him and the rest of my students—who they are as learners, as parts of distinct families and cultures, and as individuals. Home visits are the best method to do this. They aren’t “extra work.” They are the work. If I’ve learned anything in four years of teaching, it’s that education, at its core, is immensely personal. Building trust and a connection between myself, my students, and their families, is what lays the foundation for real academic growth.