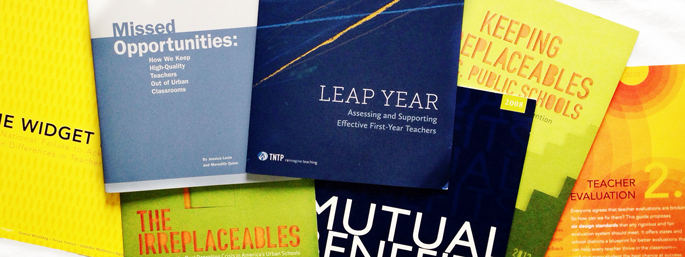

Ten years ago, TNTP published a brief report that changed our organization in a permanent way. It was called Missed Opportunities: How We Keep High-Quality Teachers Out of Urban Classrooms. Based on data drawn from four urban districts, it made a straightforward argument: the failure to hire excellent teachers into urban districts was driven more by dysfunction and late hiring timelines than teacher shortages or lack of teacher interest in urban communities.

To be honest, we had no idea at the time that the report would get the attention it did. We didn’t know it would cause us to make policy research a core component of our work. At the beginning, we just wanted to disprove what we saw as widely believed myths with rich data.

Here are the four lessons that stand out to me, 10 years later.

- It takes time for evidence to carry the day. In Missed Opportunities, we were able to show in excruciating detail that urban districts attracted qualified applicants but failed to act early enough to hire them, leading them to eventually hire whoever was left. We did not have effectiveness data on the teachers who were hired, but we could see pretty clearly that those with more attractive credentials were being lost. Nonetheless, for years afterwards, we had district HR directors and union leaders swear to us that this was not a problem in their district. Time after time, we have had to collect local data to document the pattern, again. We’ve yet to find a district with a late hiring timeline that isn’t compromising the quality of its workforce, but we still encounter plenty of resistance in some of the districts where we work when we suggest streamlining teacher transfer processes, identifying retirements sooner and locking up top prospects early in the hiring season. Despite a good deal of progress on this issue, it’s still a leap for some folks to see how it plays out in their own communities.

- One question leads to another. Missed Opportunities showed that poor hiring practices were caused by a broad array of problems, one of which was provisions in collective bargaining agreements with teachers unions. Even the most aggressive districts could not hire early enough because of prolonged contractual posting and bumping processes. But why? Why would unions tolerate hiring dysfunction that diminished the quality of the teacher workforce. . . which also diminished the quality of the union membership? It seemed baffling. So we wrote another report that looked specifically at how union contract rules prevent schools from making smart hiring decisions. This one, called Unintended Consequences, arrived in 2005. It caused substantial tension between our organization and unions, which was new for us. We were advised by some friends in the education space not to publish it, specifically because we could be made a target. But the data were too clear to deny—low-income students were getting the short end of the stick when their schools couldn’t choose their own faculty and instead got the teachers no one else wanted. We published, and eight years later, we’re still standing.

- Districts are sitting on mountains of unused information. We were able to write Missed Opportunities because TNTP staff were working on-site in districts. They saw the boxes of applications from interested teacher candidates that went unopened and unprocessed for months. Though the districts were not logging those applications into a centralized data system, our folks realized we could learn a ton by capturing and organizing the traits of the applicant pool. And that’s what allowed us to write the report. For future reports, we painstakingly traced the movement of teachers between schools, tallied up hand-written teacher evaluations and unearthed large databases that were said to be non-existent by district staff (who really were unaware that such data were being stockpiled, sometimes for years on end). We may not be uniquely gifted as researchers, but we’re not afraid to burn through shoe leather if it helps us answer our questions.

- It’s a mistake to write reports just for the sake of writing them. Whenever we publish a report, folks ask us what the next one will be about. And the answer is usually that we have no idea and we’re too exhausted to even consider the question. After Unintended Consequences, we did nothing for about two years. We didn’t even discuss another report. Then we became intrigued by debates about dismissing tenured teachers. Some folks said it rarely happened because the red tape was endless, while others said no, it can be done, but principals just won’t take the steps. That sounded interesting: Could both of those positions be valid? Two years later, we published The Widget Effect. Then we took about a year off before we began to wonder why, after decades of focus on giving low-income schools access to the best teachers, that goal seemed to be accomplished so rarely. After putting teacher retention patterns under the microscope, we found our answer, and in 2012 we published The Irreplaceables. In each case, we wrote because we had a compelling question, not because we were scheduled to publish. So what’s next? I’ll share only that we’re obsessed with teacher improvement. Where we’ll land, nobody knows.

To everyone who ever worked on one of our reports, thank you. You have the battle scars. But you also have our gratitude. Thanks to the funders who had incredible faith in report proposals that were long shots at best. And thanks to everyone who has downloaded, shared, commented on, or disparaged the reports, too. Our hope was to influence the debate about teachers with a fresh perspective. With your help, we made some progress in that direction. In the next 10 years, we’ll make a little more.

Our thanks to:

Jessica Levin, Meredith Quinn, Christine Foote, Kaya Henderson, Meredyth Hudson, Krystal James, Michelle Rhee, Ariela Rozman, Doug Scott, David Sigler, Andrew Sokatch, Rachel Szarzynski, Victoria Van Cleef, Veenay Singla, Jodi Wilkoff, Jennifer Mulhern, Emma Cartwright, Tysza Gandha, Megan Garber, Jasmine Jose, David Keeling, Metta Morton, Laura Nick, Daniel Weisberg, Susan Sexton, Ann Palcisco, Kelli Morgan, Dahlia Constantine, Timothy Daly, Vinh Doquang, Adele Grundies, Crystal Harmon, Dina Hasiotis, Ellen Hur, Gabrielle Misfeldt, David Osta, Jeffrey Wilson, Rachel Grainger, Judith Schiamberg, Caryn Fliegler, Elizabeth Vidyarthi, Melissa Wu, Jennifer Hur, Kymberlie Schifrin, Lisa Gordon, Gina Russell, Hai Huynh, Sandy Shannon, Andy Jacob, Kathleen Carroll, Amanda Kocon, Crystal Harmon, and Aleka Calsoyas