If ever there was a time for school systems to reimagine their workforce and talent strategies, it’s now. Emerging from the pandemic, there’s a sense of urgency to provide pathways to academic, economic, and social mobility for students, but educators are often stretched thin, burned out, or overworked. Our partners in school systems nationwide report the same concerns time and time again: their schools are short-staffed and filling vacancies is their biggest talent challenge.

Surprisingly, however, most public schools actually employ more teachers than they did before the pandemic, while serving fewer students. And while some school districts have multiple vacant teacher positions, (especially in hard-to-staff subject areas like multilingual, special education, and STEM), it turns out that widespread teacher shortages haven’t come to pass nationally.

So, what’s going on? Why don’t the teacher vacancy numbers reflect the capacity challenges and feelings of scarcity that so many districts and schools are experiencing?

As we outline in TNTP’s newly released Talent Framework: Designing the Workforce of Tomorrow to Support All Students’ Learning, data is a powerful way to understand what’s behind the staffing challenges that are so disruptive to students and educators alike. We looked at data from two school districts that reported facing teacher shortages, to learn what other factors might be causing schools to feel short-staffed and students to have disrupted classroom experiences.

We expected to see that disrupted classroom experiences have gone up overall since the start of the pandemic. But we did not expect to discover that most classroom disruptions were not caused by teacher shortages or by vacant teacher positions. The biggest factor in disrupted classroom experiences? Teacher absences.

In the traditional school staffing structure, one teacher is in charge of one classroom, so when that teacher is absent, learning tends to stall. Studies have associated increased teacher absences with lower growth on students’ test scores. In addition, the difference between having a teacher with zero absences and one with 10 days of absences is akin to “the difference between having a novice teacher and a teacher with a bit more experience,” when it comes to average math achievement.

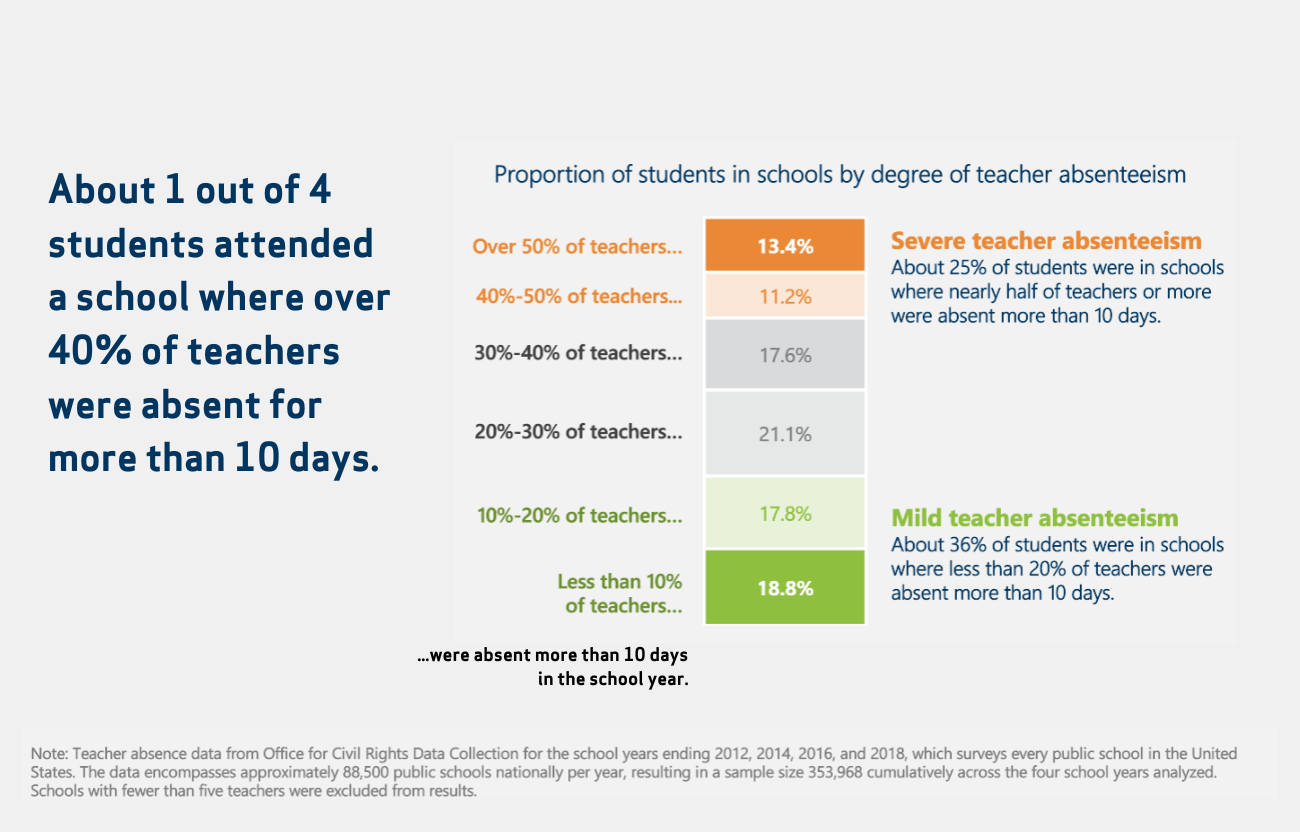

Even before the pandemic, one in four students attended a school where over 40% of teachers were absent for more than 10 days (not including professional development days)—a measure the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights considers “chronically absent.” This same federal data found that between 2012 and 2018, nearly a third of teachers nationwide met the criteria for being chronically absent. Schools with higher levels of teacher absenteeism tended to serve slightly more students experiencing poverty. The schools were less likely to be high achieving and less likely to grow students’ achievement over time.

What is a disrupted learning experience?

When students miss 10 percent of the school year, they are typically considered chronically absent. In alignment with that bar, we based our definition of a disrupted learning experience on whether students did not have access to their permanent teacher for at least 10 percent of the school year. This could be when a teacher:

- Was hired late or resigned early and therefore missed at least 10 percent of school days during the year.

- Was absent at least 10 days in a row, leaving students without a lead instructor for at least a two-week block

- Missed at least 10 percent of school days throughout the year.

To explore disrupted learning, we partnered with two school districts serving mostly students of color and many students who qualify for free and reduced-price lunch. Both districts are large, with total student enrollments that rank in the top 500 nationally.

In both districts, more than 90 percent of disrupted learning experiences were due to teachers either missing 10 percent of school days or being absent for at least two weeks in a row. In other words, even in a fully staffed school, we can still expect to see students experiencing significant classroom disruptions. And those disruptions have a ripple effect across the school, from leaders scrambling to find coverage to other educators losing preparation time or taking on additional duties to fill the gaps, and beyond.

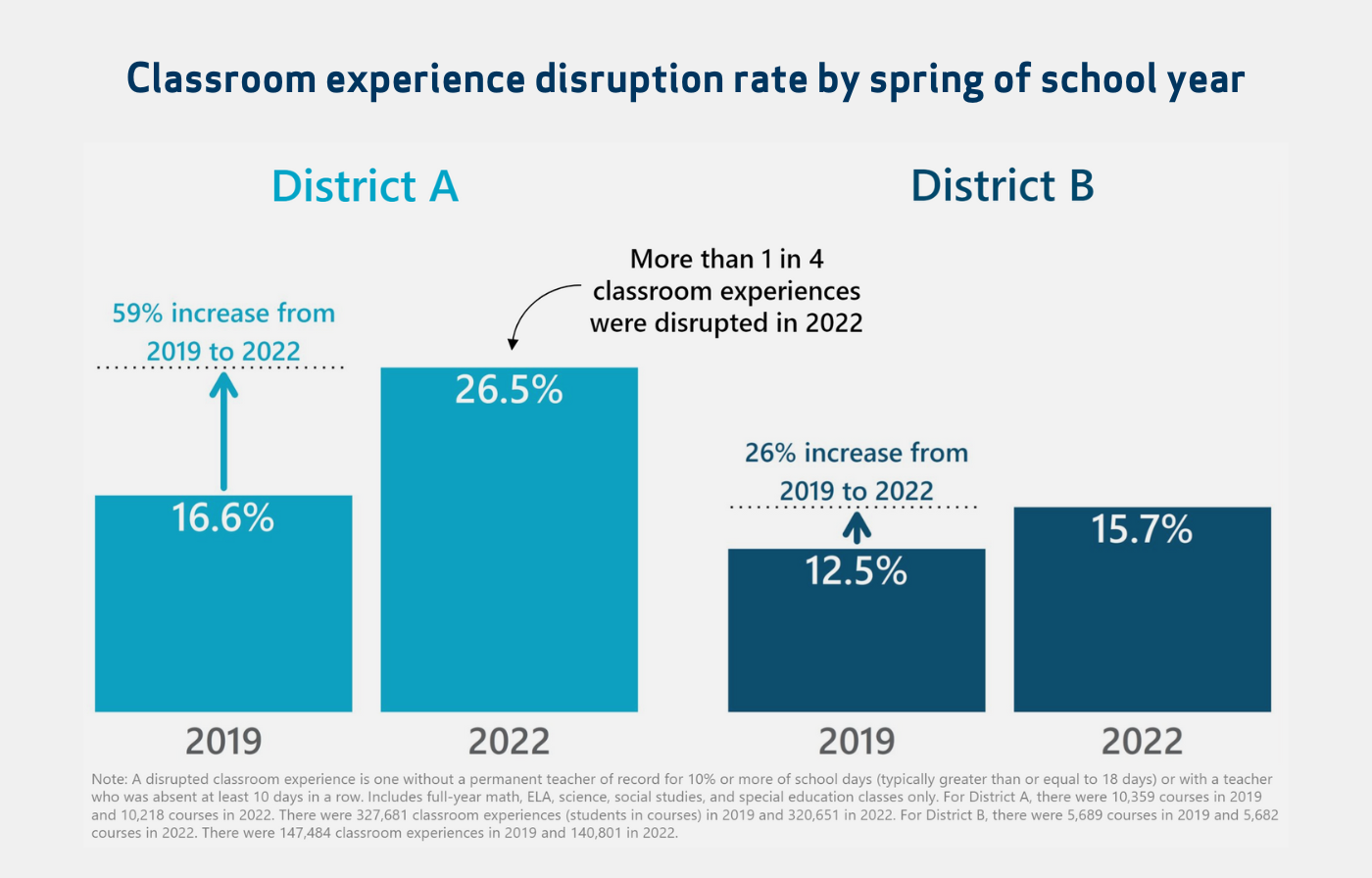

We also looked closely at how the districts’ rates of disruption changed before and after the pandemic, and found that in one district, more than one in four classrooms were disrupted in 2022, an increase of 59% since 2019.

Classrooms were disrupted before 2020, but the rate of disruption was exacerbated—in many cases sharply—by the pandemic. Lower-achieving schools and schools with lower achievement growth tended to have more disrupted classrooms.

What can school and district leaders do?

Let’s say this loud and clear: teachers—like all workers—must be able to miss work when they are sick, require a personal day, or are on vacation. But it’s also vital that students be able to continue engaging, without disruption, in high-quality, consistent learning. The current one-teacher-one-classroom setup just isn’t sustainable. But there are steps that school and district leaders can take now to address this challenge:

1. Use data to understand the root causes of students’ disrupted learning experiences.

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights collected teacher absence data at the school level as recently as 2018. School systems can leverage the agency’s data collection infrastructure and process to drill down to the root causes of their students’ disrupted learning experiences. By developing strong metrics focused on the student experience and tracking them over time, education officials can gain a better understanding of how and what types of disruptive experiences impact student outcomes most negatively—the first step toward addressing the issue.

2. Leverage TNTP’s new Talent Framework to reimagine the teacher role.

Teacher absences are so disruptive because most schools and school systems still rely on one teacher instructing one classroom of students, and that one teacher is responsible for everything—from planning to instructional delivery to grading to following up with students when they are behind. Expanding the teacher role to a team of adults with shared responsibility for the learning in a particular grade level or subject area would help make one educator’s absence far less disruptive.

TNTP’s 7-P Talent Framework is a new resource created to support school and system leaders in designing a workforce strategy that directly aligns with their vision for students’ experiences.This comprehensive framework presents schools and district leaders with creative ways to think beyond the traditional staffing model and to pilot new approaches. For instance, one skilled secondary math teacher may take the lead on designing instructional materials, while a small team of novice or student teachers delivers lessons. Tutoring may be outsourced to a community organization. Roles can become fluid: perhaps instead of being assigned to one school, elementary specials teachers or secondary science teachers could serve multiple campuses.

Even prior to the pandemic, teachers were already working at or beyond capacity. It’s more important than ever to make sure students have consistent, daily access to effective teachers to counteract unprecedented amounts of unfinished learning—especially given recent evidence that students’ academic recovery stalled in the 2022-2023 school year— and to make the work of being a teacher more sustainable.

TNTP is ready to support schools and districts in deeply understanding their staffing data and developing innovative plans that allow teachers to take the time they need and deserve while minimizing disruptions to student learning. Contact us to get started.