For students in 2017 Fishman Prize Winner Maria Morfin’s classroom, immigration isn’t politics—it’s lived experience. In her essay, Morfin describes how she teaches her fifth-grade English students to cut through the noise of current events, evaluate arguments and evidence, and form their own identities and perspectives at a time when their community—and their families—feel threatened.

“Are my parents going to be okay?” Cesar asked as he left my class. “Are we going to be separated?”

I wanted to say, “It’s going to be all right.” Instead, I said, “Your parents love you, your family loves you, and there are many adults in this building who also love and care about you. All the adults who love you will do their best to take care of you and to make sure you are safe.”

I could not look Cesar in the eyes and say with certainty that he and his family would not be separated. I was equally uncertain about my role as his teacher in easing his fear at a time when the national debate over immigration and who belongs in America can make my students feel unwelcome—and unsafe. Should I add my own beliefs to the many people and sources telling Cesar what to believe?

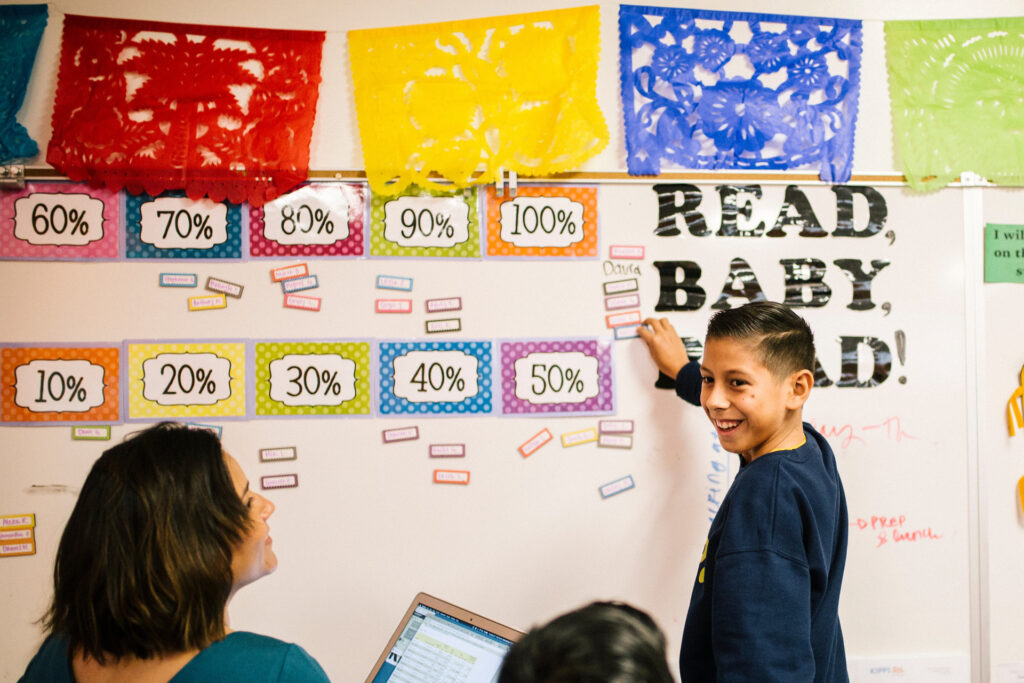

After my encounter with Cesar, I reflected on how I could answer the difficult questions about the possible implications of immigration raids, the construction of a border wall, and the negative portrayal of immigrants in the media. When my principal, Mrs. Minix, designed Sol Academy, she envisioned a school where students are not just students; they are advocates. As Mrs. Minix says, at Sol, we believe that if we are to create advocates, our students must have “the ability to define themselves, name themselves, create, think, and speak for themselves so that they do not risk being named, created, or spoken for by others.”

But I don’t have to develop my students’ advocacy skills at the expense of developing their academic skills. While I cannot predict the future for Cesar, I can provide opportunities for him to practice his advocacy skills by helping him comprehend the information presented in text, evaluate the details, create evidence-based arguments, and engage in discussions to support or challenge an argument—all of which are demands of the fifth-grade ELA standards.

I intentionally chose not to focus our learning on Cesar and his peers’ concerns about the future of their family in this country. Instead, we attempted to unwrap how place shapes identity through the lens of the travel ban on the seven Muslim countries.

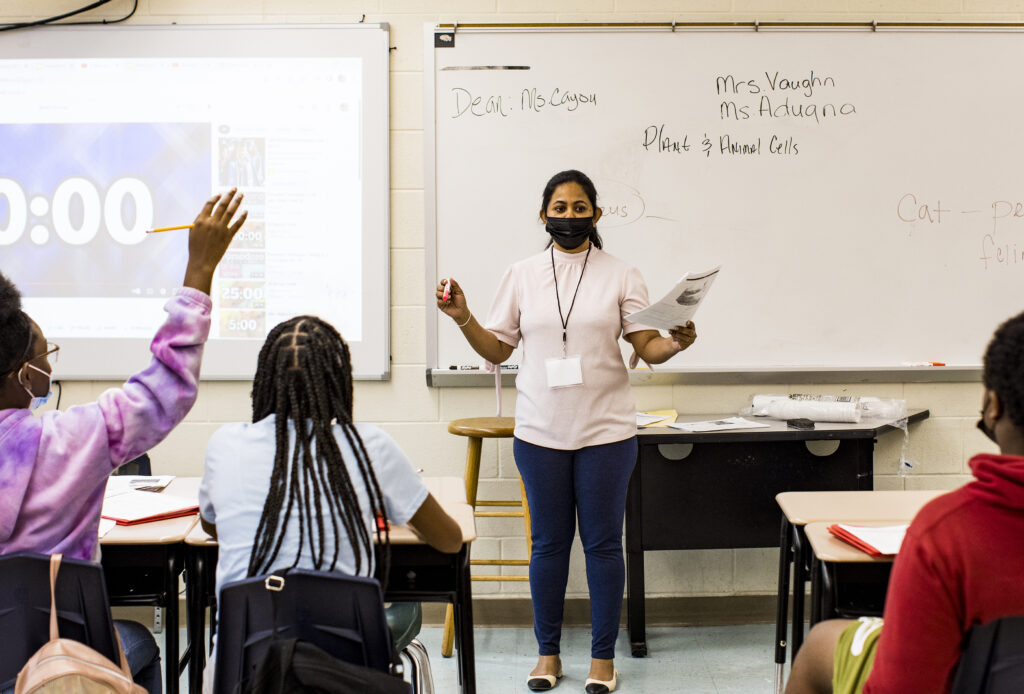

Students read current event articles modified for readability from NewsELA and news outlets about the President’s travel ban on the seven Muslim countries, each with a different point of view. We spent over a week building background knowledge on the countries listed on the ban, learning new vocabulary words, annotating and closely reading the articles, and responding to comprehension questions.

Axel read the first question to the class, “Should the President keep the ban on the seven countries, or should the President get rid of the ban on the seven countries?”

We sat silently for a minute while students shuffled through their articles and notes, gathering their thoughts.

“In the text, it says that a person from one of the banned countries came to the United States and he exploded a bomb in the Boston marathon,” claimed Kevin. “Why would we want to allow someone dangerous into our country?”

“I respectfully disagree,” said Alexis. “In one of the articles, it says that only a small percentage of terrorist attacks in the United States were committed by terrorists from the seven banned countries. Just because one or two people from one country are dangerous does not mean everyone from the country is dangerous.”

“I agree with Alexis. It’s like the President and other people say Mexicans are violent and lazy and that’s not true. Maybe there is one Mexican who is lazy or violent, but that does not make us all lazy,” Jackie said.

Their bodies and eyes shifted towards the side of the classroom where I sat taking notes. I knew what my students were seeking. They wanted some affirmation about Jackie’s comment from the adult in the classroom. But rather than stepping in, I continued to encourage the students to lead the discussion and asked, “What else are we thinking?”

“Well, I think the President should remove the ban. In the text, I read that one of the banned countries is Syria.” Jacob paused, sifted through his notes, and then continued. “I also read in another text that there’s a war in Syria and a lot of Syrians want to leave Syria to protect themselves. I think the President should remove the ban because we could be saving people from the dangers of war.”

By the looks on their faces, I could tell that students were beginning to formulate their own opinions about the ban, listening to each other and questioning the information in the articles. While I did intervene a handful of times to push students to elaborate or to clarify misconceptions, not once did I provide my point of view. Because, when I step down from the conversation, students become active learners and are empowered to define their own voice—rather than having that voice defined by others.

Read more about Maria's classroom in her essay, “Students Define Themselves: Debating Social Issues in the Middle School Classroom.”