Over the last two decades, researchers have confirmed what we’ve all known intuitively:

- Great teachers matter, and some teachers are better than others.

- Veteran teachers tend to outperform novices, but the learning curve is steep, and a teacher with five years of experience is virtually indistinguishable from someone with 15 or 20 years in the classroom.

- A teacher’s academic credentials are not predictive of how well he can teach.

But as Carolyn Chuong and I discuss in our new paper for Bellwether Education Partners, Teacher Evaluations in an Era of Rapid Change: From “Unsatisfactory” to “Needs Improvement,” districts continue to ignore the value of great teaching. In fact, despite the development in recent years of new, multiple-measure teacher evaluation systems, the vast majority of school districts continue to treat their teachers the same in terms of how they’re paid.

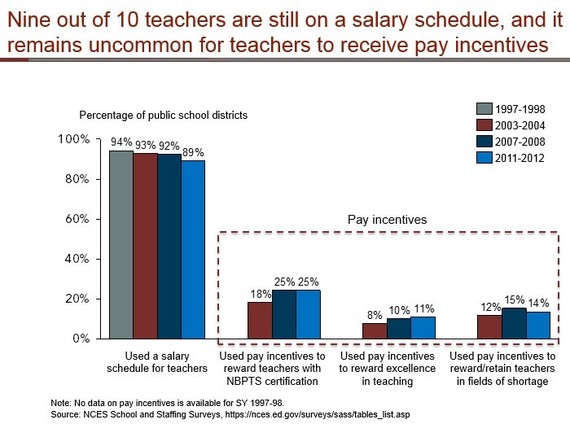

Consider the numbers: In 1997-98, 94 percent of districts paid teachers based on a lockstep teacher salary schedule. That number has fallen, but only slightly, to 89 percent. As of 2012, only 11 percent of districts rewarded teachers with base salary increases specifically for excellent performance. TNTP’s recent report does an excellent job at documenting the consequences of this rigid attachment to the traditional, mechanistic method of paying teachers.

Paying teachers for their performance can be controversial because it requires agreement on how to measure it (and whether it’s fair to pay teachers based on the outcomes of their students). But other types of financial incentives that could be more politically palatable haven’t become widespread either. The National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS) has developed high-quality educator certifications that supplement traditional teaching licenses. These certifications are a potential signal of teacher quality, and the voluntary, peer-reviewed process doesn’t depend on the results of high-stakes state exams. It would be worthwhile to reward teachers who undergo the NBPTS certification process with financial incentives, but only one-quarter of school districts did so in 2012.

In most professions, employees with special skills or those who are willing to take on difficult tasks receive extra compensation. But the vast majority of school districts treat all teaching positions the same, as if they were all equally desirable and the laws of supply-and-demand don’t apply to schools or teachers. According to the most recent national data available, only 14 percent of districts offer teachers an extra incentive to staff a hard-to-fill position.

It’s also instructive to look at the level of incentive districts offer. For example, the Fort Wayne, Indiana school district now rewards teachers with an “Effective” or “Highly Effective” rating with a base salary increase of $1,100. About 84 percent of teachers qualified in 2013. This is an improvement from the prior contract, which offered nothing specifically for great teachers. But rather than striving for a high evaluation rating, Fort Wayne teachers might be better off earning a master’s degree—because according to the same contract, that would earn them $4,000 more per year, regardless of effectiveness. The district is willing to pay teachers almost four times as much for a credential than for actual classroom performance.

While educators typically don’t enter the profession for financial reasons, money is one of the few incentives school districts have at their disposal to recruit and retain educators. And very few districts use cash to reward or retain their best employees.

In recent years, states have made sweeping changes to the way teachers and principals are evaluated. Districts are starting to evaluate teachers as professionals, rather than as interchangeable widgets. Where once they saw only black or white—satisfactory or unsatisfactory performance—schools are starting to see nuance through the use of multi-tiered evaluation systems. The results of those evaluations, however, are still too often divorced from what happens to students and how much they learn. And districts rarely make consequential decisions about the adults working in their schools based on their on-the-job performance.

To read our full take on the last few years of the new evaluation systems and the preliminary lessons for policymakers, download the report here.