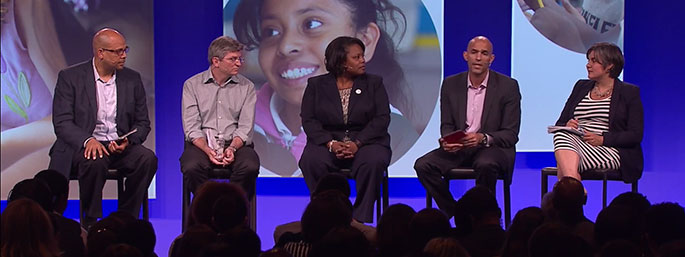

On the last day of the NewSchools Venture Fund Summit last week, it was an unseasonal 90 degrees outside in San Francisco—but inside the final session, it was even hotter. Deputy Secretary of Education Jim Shelton led a panel discussion on diversity in education leadership, and something special happened. They had a real, honest, at times uncomfortable conversation about race and education reform—and they had the crowd on their feet.

The panel featured an all-star cast: D.C. Public Schools Chancellor Kaya Henderson, KIPP CEO Richard Barth, John Rice of Management Leadership for Tomorrow and Teach for America co-CEO Elisa Villanueva Beard. Dr. Howard Fuller and NSVF Managing Director Deborah McGriff also gave remarks.

This discussion of diversity in education matters for a whole host of reasons. As Elisa pointed out, nationwide, more than 40 percent of students are children of color, compared to less than 20 percent of teachers. And in the communities where reform is focused—in the Newarks and Harlems and Memphises where we work—African American and Latino students compose large majorities in public and charter schools. Meanwhile, most of their teachers, their principals, and the district, state and organizational leaders driving changes to their schools are white.

Chancellor Henderson spoke a hard truth when she said, “The people we serve have to be part of their own liberation.” Communities need to own the work of their schools’ improvement, Kaya said, and Elisa argued that successful reform requires not only leaders who care about the work, but also those who have walked in our families’ shoes. If those voices aren’t at the table, she said, none of us should be so sure we’re doing the right thing.

The panel struck a particular chord with the crowd—who were clapping and finger-snapping in support—when they dug into the issue of access to capital, the power dynamics embedded in the funding process, and the consequences on both the perception and realities of reform. Chancellor Henderson spoke of the challenges leaders of color face when seeking funding. Money seems to pour into schools and districts run by white leaders, she said—even when those schools are generating only modest results for kids. Meanwhile, black and Latino leaders who are producing results continue to struggle to get funds.

Doing good work isn’t enough for leaders of color, Henderson said; it’s also about access to those in control of the money. John Rice pointed out that success requires convincing people to “take a bet on you,” to build trust and network successfully within the existing power structure. Richard Barth added that those with ready access have a responsibility to look beyond their present circles, for others who might be doing great work but not have a foot in the doors of the boardrooms and offices where decisions are made.

The message here is clear: Even for some of the most visible and accomplished leaders in education, there are uncomfortable questions of race and class. For me as an African American woman who grew up in one of the poorest parts of the South, it was incredibly validating to hear such candor.

While real conversations about race in education can be uncomfortable, we have to have them. This takes courage for all of us—for the people of color in the room, and for our white colleagues, too. But shoving these tough conversations under the rug will only result in solutions that are put upon communities, rather than developed from within them. And our historical reluctance to address race (and, by extension, poverty) head-on in reform perpetuates the public perception that we are out of touch with the experiences of the students and families our work affects.

The panel challenged audience members to commit to improving diversity in education right then and there, via text message. As we sent our texts, the screen lit up with the names of more than two hundred individuals and organizations pledging their commitment. Now it’s time to hold ourselves to those promises. For our part, we’re pushing hard in our PLUS programs in Philly and Camden to support pipelines of school leaders that emerge from the local communities, and we’re continuing our focus on building diverse cohorts of Teaching Fellows. But like everyone else, we can do more.

Cracking open the conversation is just the beginning—and the consensus on the panel was that talk is good, but action is essential. Kaya challenged the crowd to get in the arena with her and do the work. “Don’t just blog about what a good job I’m doing,” she said.

Well, I couldn’t help but blog about it. But we’re amped up to do the work, too.