Publication: Room to Run

One Classroom, Twenty Teachers

Martin’s Story | 10th – 12th Grade Math at Earl J. Lennard High School in Ruskin, FL

Martin Rangel, 17, is a junior in Kelly Zunkiewicz’s pre-calculus class at Earl J. Lennard High School in Ruskin, Florida. He didn’t always want to be.

Chatty and quick to smile, Martin isn’t shy about the fact that he wanted out of pre-calculus at the start of the school year. He viewed pre-calculus as “stuff maybe really, really smart people do.” Martin had always been good at math, but this felt beyond him.

“I wasn’t really confident that I could be successful in this class. That’s why I wanted to get out.”

But Martin didn’t leave pre-calculus. Today, he’s very clear on why he stuck with the class: a big push from his teacher and the support of his fellow students, who, in Ms. Zunkiewicz’s skilled hands, become co-teachers.

“Ms. Zunkiewicz strategizes on how people can work together in a way that works,” Martin explains. “It helps because anything one person doesn’t know, the other person might know. It’s like joining forces. That’s how we do everything.”

The Lennard Longhorns

Ruskin sits on the gulf coast of Florida, 40 minutes south of Tampa. Pastel fish shacks, signs for the local manatee viewing center, and an old-fashioned drive-in movie theater dot the main drag; strip malls alternate with acres of undeveloped swampland to give Ruskin a feeling of rapid, if incomplete, change.

Thanks to a recent population boom, the student body of Lennard High School—which serves Ruskin and two neighboring communities—has nearly doubled in the last few years. Today, Lennard serves an ethnically diverse group of more than 2,000 students, some three-quarters of whom qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. Many, like Martin, are first-generation college-bound.

Ms. Zunkiewicz checks in with students as they work in groups.

During first period on a Monday morning in February, Martin and his classmates settle themselves at tables of four and immediately get to work. At the start of every class, students have “flex time” to check homework or work on quiz corrections or a warm-up problem that builds upon the previous day’s work. Ms. Zunkiewicz circles the room, asking quiet questions to keep conversations moving. “How are we doing here? This is all you’ve got?” she teases. “Talk about it. Think about it.”

The table groups are carefully selected to pair students with complementary strengths and weaknesses, so they’ll be able to support each other effectively. Ms. Zunkiewicz experiments with groupings in the beginning of the year, but once she gets them right, she says, they stay that way.

In many respects, the groups are at the heart of Ms. Zunkiewicz’s classroom culture—and one of her most important teaching strategies. Because besides those quiet, guiding questions—the result of the meticulous planning she does in advance of every lesson and her deep knowledge of both her content and her students’ needs—Ms. Zunkiewicz barely says anything during class. Her students do all the work.

This means Ms. Zunkiewicz’s math class looks very different from her students’ previous math classes. It’s not just that the teacher does less talking. In Ms. Zunkiewicz’s room, students themselves are actually discovering how to do high-level math as they go along, using their prior knowledge, their classmates’ ideas, and their best guesses.

In a recent lesson, for example, students used their prior knowledge of the Law of Cosines to derive the Law of Sines in their groups. Ms. Zunkiewicz used questions about triangles to help them focus on the right information: “What do you have to have specifically from the triangle to use Law of Sines?” Once they understood that they needed two sides and a corresponding angle, or two angles and a corresponding side, she asked, “What kind of triangles would that be used for?” She let them work toward their own organic understanding, increasing the difficulty of the problems they tackled as they built their knowledge.

Developing knowledge organically like that is a different level of challenge than most of these students have been exposed to in math before—and the expectations for the level of understanding they’ll reach as a result are higher, too.

Asked what makes her class different, her students explain again and again that in previous classes, teachers told them, “This is how you do it.” That’s not how it is in Ms. Zunkiewicz’s class.

Katie Hartwell (left) supports her group’s understanding of the derivative.

We’re All Teachers to Each Other

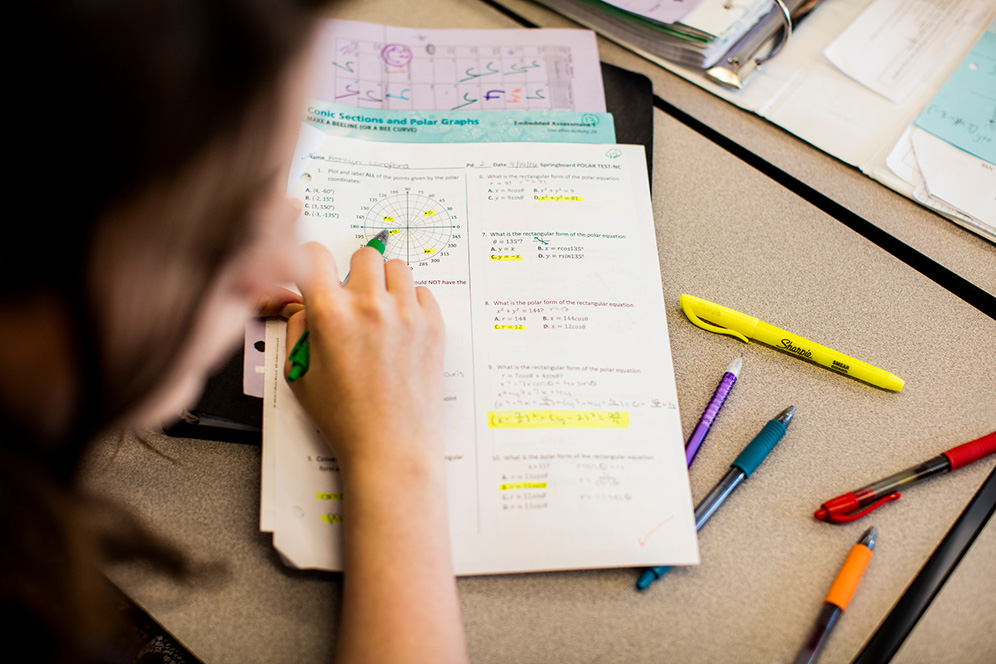

On Monday morning, students are using their flex time in the beginning of class to go over a recent quiz.

Ms. Zunkiewicz’s approach to tests is to enter students’ grades in her records but return them without grades marked on the papers. Instead, where a student has arrived at the wrong answer, she highlights the last thing they did right so students can correct their own mistakes, with the help of their peers.

A student revisits her quiz.

This is an approach she adopted just a year ago, after watching a middle school science teacher use it in a video on the Teaching Channel, where she gets a lot of ideas. Rather than stuffing graded quizzes in their backpacks and never looking at them again, students are forced to revisit the content until they really understand it.

While she doesn’t give them points back on their quizzes for the corrections, Ms. Zunkiewicz believes her students get more out of the assessment process this way.

This is also one of the many ways Ms. Zunkiewicz turns her students into teachers. At one table, four young women go over their quiz results together. Jamaris Rivera, 16, who missed the test and will have to retake it, isn’t checked out of the lesson, as one might be in a classroom where students take less active teaching roles. Instead, she nudges her partner, Michaela Frasier, through a tough problem, until they both hit a roadblock.

Ms. Zunkiewicz pauses at Michaela’s shoulder. “I’m trying to think,” says Michaela, 17, explaining where she and Jamaris got stuck. “If this is negative two cosine squared, would that turn into…this?”

Ms. Zunkiewicz considers the girls’ work. “So is that a positive two, or a negative two?”

Michaela pauses, uncertain, then laughs. “I’m just asking,” says Ms. Zunkiewicz.

“I don’t know.”

“That’s all right. Let’s go from here. This right here—this is awesome. What do these have in common?”

Ms. Zunkiewicz waits while Michaela stares at the page, then brightens. “I get it!”

“What do you get?”

“Factor out the two!”

“And then what would you do from there?”

Michaela explains her next steps, and Ms. Zunkiewicz nods. “You got it.” She moves on to the next table, and Michaela—after a quick high-five with Jamaris—gets on with her quiz corrections.

Jamaris Rivera helps a classmate with a quiz correction.

Ashlyn Langford sits on the steps of Earl J. Lennard High School.

Around the room, similar conversations are taking place—from student to student, involving Ms. Zunkiewicz for support only when they’ve exhausted the resources available at their table. While Zak Saumell, 16, walks through the quiz with his tablemate, he describes the value of this kind of teamwork: “If we have two or three different ways of solving the same problem, the next time, if I get stuck, I might try a different way.”

We’re all teachers to each other. Having to teach it to somebody else, you get a better understanding of what you’re talking about.

– Ashlyn Langford, 16

Zak’s partner, Ashlyn Langford, 16, agrees. “We’re all teachers to each other. Having to teach it to somebody else, you get a better understanding of what you’re talking about.”

These teenagers explain that when they reach that level of understanding, they can solve problems even when they forget a specific formula—because they know why the formula works the way it does. As far as Ms. Zunkiewicz is concerned, that is exactly the point.

Greater Challenge, Greater Reward

The high expectations Ms. Zunkiewicz holds for her students pay off. For the last four years, Lennard High School has come first in the district’s pre-calculus end-of-course exam—by a wide margin—among the 27 Hillsborough County schools that offer it. It’s an accomplishment she and her students take seriously, and they are fiercely competitive about maintaining it.

“How I see it coming here in this classroom, sitting here in this classroom…That’s me hustling to get where I gotta go. You know, I don’t have to be out there, selling dimes and this and that. I’m going to be in here, safe. My family’s safe.” –Noe Garza

“These kids know this isn’t the top school in the county. They’re talked about in ways they shouldn’t be talked about,” Ms. Zunkiewicz says. “When they find out they’re number one, it’s like, ‘See, I told you!’”

The high bar also pays off for many students for whom the lessons of math class extend to other subjects and, indeed, the rest of their lives.\

She doesn’t give us the answer. Even though it may frustrate us, it’s better for the long run.

– Noe Garza, 18

Noe Garza, 18, is a senior in Ms. Zunkiewicz’s AP Calculus class. Soft-spoken and modest, he says he’s always been “above average” at math—his favorite subject—but he wasn’t always a high achiever. In his early years in high school, Noe hung out with a large group of friends, most of whom are no longer in school. But since Noe joined Ms. Zunkiewicz’s class for pre-calculus, he says she’s pushed him to stay on track.

“I haven’t been in trouble for the last two years,” he says. “Ms. Zunkiewicz sets the bar really high for us. She believes in me, so I went out to try to do what I had to do to fulfill my potential.”

How did Noe go from a student who did “lazy work,” as he calls it, to AP Calculus and college applications? He’d always set his sights on college, but it wasn’t clear to him that he’d get there.

“That was always my goal,” he says assuredly. “High school’s not enough for me, I believe. But I have a lot going on, and it’s really hard.”

Working long hours outside school—Noe works at a retirement community, serving and bussing tables—makes it a challenge to keep up with his course work. Now, the stakes are even higher. Noe and his girlfriend recently welcomed a baby girl, Ilee Rose.

“I look forward to getting a degree, and then getting a job right away and making money,” he says. “I always wanted that, but having a daughter made me hungrier.”

“I want a better life for Noe and I want him to have an even better life than I ever imagined. That’s always been my goal for all my children.” –Maria Martinez

Noe’s mother, Maria Martinez, expects great things of him, too. She’s pushed him to take his education further than she did.

“I came from a migrant family,” says Ms. Martinez. “We had nothing. I grew up working in the fields, picking tomatoes and strawberries. I knew when I was young this is not what I want for the rest of my life.”

Ms. Martinez was a straight-A student in high school—like her son, she loves math—but when Noe was born in the beginning of her senior year, she didn’t have the support at home to continue her education. “I had the scholarships for university, but I was scared.”

She’s always known her children would have the support and security that she lacked, to meet their full potential. For her oldest son, that means pursuing a degree that will allow him to use his interest and skills in math.

But to be prepared for college-level math, Noe needed opportunities to wrestle with challenging enough content in high school. That’s what he got when he entered Ms. Zunkiewicz’s pre-calculus class as a junior.

Ms. Zunkiewicz never lets him get off easy. “She doesn’t give us the answer,” says Noe. “She asks you questions because she wants you to figure it out, when most of us are used to a teacher telling us, ‘This is it.’”

He smiles. “I do get frustrated with her, because she challenges me. She expects perfect out of us. But that’s what we should do. I believe that the expectations are right for all her students. I never told her to take it easy on us. Sometimes I say, ‘That’s it? That’s all the homework you’re giving us?’ Even though it may frustrate us, it’s better for the long run.”

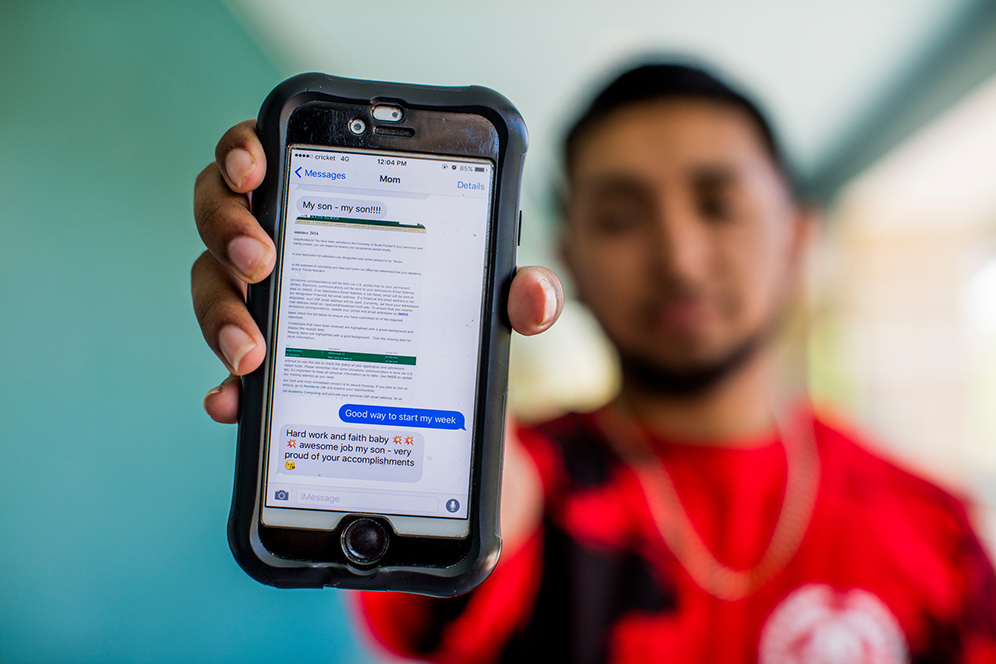

“When I clicked in and it said, “Congratulations,” I started crying. I was home alone but I started crying because I was very proud of my son. This is something that he worked for and he achieved it.” –Maria Martinez

It wasn’t until Noe had mastered the challenges of pre-calculus that he thought he could tackle the AP course. “I always heard of it, but I never thought I would reach that. This is my first AP class.”

His mother and his teacher agree that Noe is capable of doing higher-level math and achieving his goals for his education and his career. “Ms. Zunkiewicz says the sky’s the limit for me,” Noe says. “She’s just trying to get me there.”

Now, Noe is a role model for his four younger brothers, three of whom are already coming up behind him at Lennard. His mother says the example he’s setting for her younger boys is shifting the tide for the next generation of their family.

“He’s starting a new cycle where it’s okay to apply yourself at school, it’s normal to go to college. I want that to be a normal thing in my family.”

To help her son and his girlfriend reach their goals, Ms. Martinez is helping out with the baby. She has even higher hopes for Ilee Rose. “I want ten times more for my granddaughter,” she says.

As for the friends he used to hang out with, Noe is reflective, choosing not to judge his friends for choices that are different from his own. But he’s not interested in changing his trajectory. “Everybody goes their own paths. I’m the only one on my path. I don’t really have time for a lot of friends anymore. I’ve got things to handle at home. I’m doing my thing.”

Doing that “thing” is paying off. On this otherwise average Monday, Noe has good news to share.

“I got a text from my mom. It was a picture of the email, saying, ‘Congratulations, you’ve been accepted.’ Next year I’m going to University of South Florida for an engineering degree.”

For his mother, it’s a dream many years in the making.

“It’s a goal I had many years ago, and he attained it, regardless of the situation. He made it,” says Ms. Martinez. “You can only do so much for your kids. It’s up to them to take the baton and run.”

A Different Kind of Math Class

How does one teacher, even one very talented teacher, prepare all her students to run with that baton, when they enter her classroom with such different strengths and weaknesses?

This is one of the fundamental challenges of the conventional classroom model. By turning a roomful of students into co-teachers, Kelly Zunkiewicz has—over many years of hard work—developed an elegant workaround.

Ms. Zunkiewicz’s student-led approach to teaching and learning isn’t random. It is designed specifically to push her students toward a deeper conceptual understanding of math. After they understand the why behind the math, students build the procedural fluency they need to solve problems efficiently.

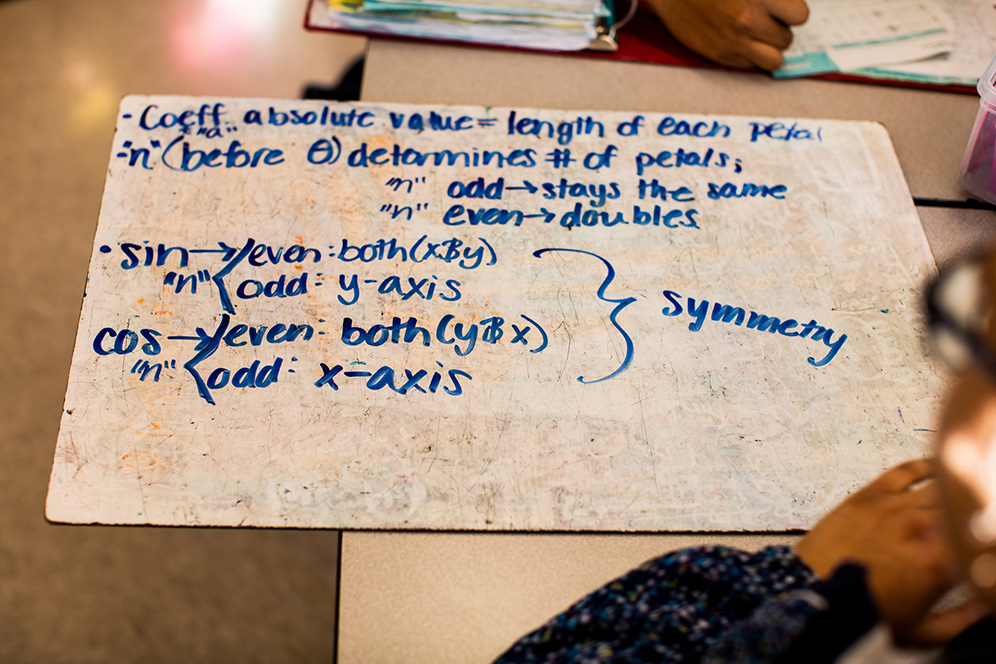

Students’ work on whiteboards helps Ms. Zunkiewicz understand their thinking.

They’ll also be better able to apply their knowledge when solving new problems, like they’ll need to do when using math in the real world. Those three pieces—conceptual understanding, procedural skill and fluency, and application—are the dimensions of “rigor” demanded by college and career readiness standards, like the ones Florida adopted in 2010.

In math, the standards also define eight Standards of Mathematical Practice, which describe the ways students should engage with math as they develop. These remain consistent throughout grades K-12, while content-specific standards are divvied up by grade. The practice standards require that students are able to, for example, “make sense of problems and persevere in them,” “reason abstractly and quantitatively,” and “construct arguments and critique the reasoning of others.”

Ms. Zunkiewicz says these eight practices are “exactly what I do in my classroom every day.” As students are talking about math in their groups, they are taking ownership over their learning and improving their understanding of the underlying concepts.

This is a fundamentally different—and perhaps counterintuitive—way to teach math. Rather than lecturing students from the front of the room and having them plug numbers into formulas, Ms. Zunkiewicz demands that her students build on their understanding of previous content to develop knowledge on a new topic.

That’s important because college and career readiness standards in math place a much greater focus on coherence than previous math standards did—meaning that students gain knowledge at each grade level that builds upon the knowledge they developed in the grade before.

From kindergarten through eighth grade, the progression is designed to build a foundation for students to master algebra—which is in turn a key indicator of success in higher-level math and even high school graduation rates. Ms. Zunkiewicz explains that when her students get stuck in pre-calculus, it’s usually not about pre-calculus; it’s because their understanding of algebra is lacking.

That’s why Ms. Zunkiewicz, who serves part-time as a math coach this year while teaching, feels strongly that every teacher needs deep content knowledge in their subject area, so they understand how the mathematical concepts and operations they’re teaching connect to the math that comes before and after.

“The basic expectation needs to be that every teacher knows more content than just what they’re teaching. Anyone in a math classroom should be able to do content for grades six through twelve. I don’t think that’s unrealistic.”

Kelly Zunkiewicz outside Earl J. Lennard High School.

Content knowledge is critical if teachers want to release so much of the teaching and learning to their students. Ms. Zunkiewicz, now in her ninth year in the classroom, says she didn’t have that when she started teaching. “I don’t think I knew the content deeply enough,” she says. “I don’t think I had a handle on how to ask a lot of those questions myself.”

A really successful Common Core classroom can look a hundred different ways. Mine is not the only way.

– Kelly Zunkiewicz

Now, Ms. Zunkiewicz plans those questions meticulously in advance.

“I’m going through the whole lesson and practicing what I’m going to say to the kids. I’m envisioning exactly what this is going to look, sound, and feel like,” she says. “That’s the only way I know how to do it.”

Getting to the level of instruction demanded by college and career readiness standards is tremendously difficult. Ms. Zunkiewicz argues that most teachers are lacking in opportunities to see this done well—both the planning and the execution.

Nonetheless, she says there are lots of different ways to reach the goals set by the standards. “A really successful Common Core classroom can look a hundred different ways,” she says. “Mine is not the only way. But we’re not seeing enough examples to really help teachers with different skill sets and personalities get there.”

The Grace to Ask Questions

If the shift toward more student ownership in the classroom isn’t easy for teachers, it is also hard for students, many of whom have never experienced a teacher who won’t give them the answer or who holds them to such high expectations for their understanding.

Put simply, this way of learning math is harder for students and teachers alike. Why do it, then?

Ms. Zunkiewicz sees the lessons extending far beyond math class. “I’m very open with them about this, that this is not easy. I’m asking you to do something that’s very hard, but you’re going to see the payoff in class next year, the following year, ten years from now. You’re going to feel so much more confident in yourself.”

Ms. Zunkiewicz presses her students for deeper conceptual understanding.

Getting students on board with this different approach takes about a month, and it isn’t always pretty. “I imagine it’s like parenting,” says Ms. Zunkiewicz. “My students complain, but what am I going to do, just give in? I know this is what’s best for them. It’s worth it.”

For students like Michaela Frasier, Ms. Zunkiewicz’s student-led approach to instruction has proven both more challenging and ultimately more gratifying than previous math classes.

“I like the challenge Ms. Zunkiewicz proposes for us in her class,” Michaela says. She says she’s been pushed to “actually understand instead of just memorize, so it’s harder.” Rather than causing her frustration, though, Michaela says that the added challenge has been coupled with a classroom environment where it’s safe to ask questions.

“In other math classes, you don’t really want to say anything because you feel like you’re the oddball because you’re wrong,” she explains. “In Ms. Zunkiewicz’s math class, you’re comfortable saying, ‘I don’t understand. Can you help me?’”

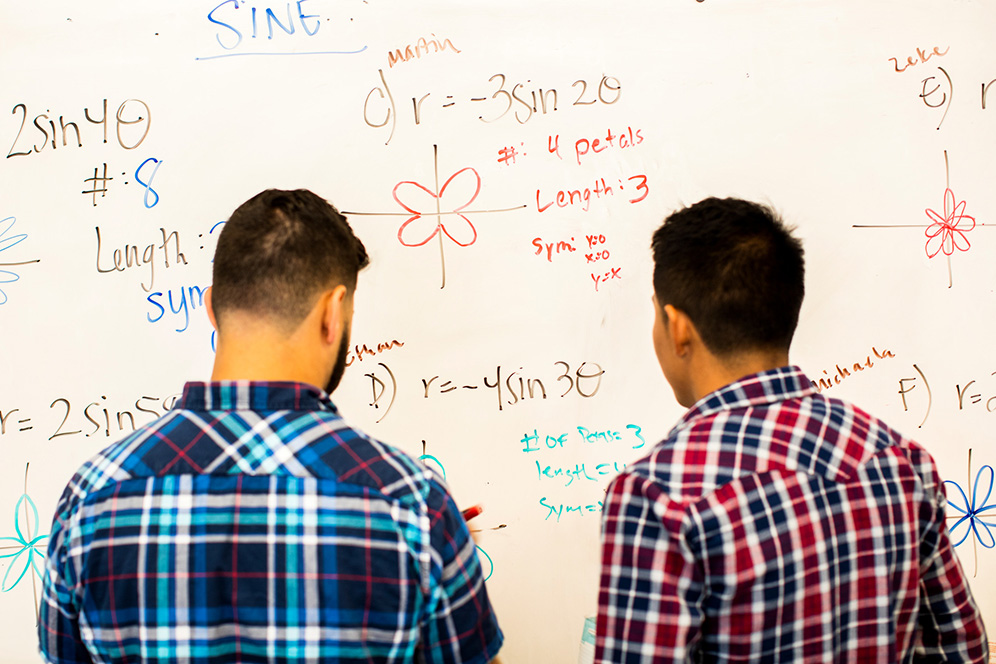

Ethan Noe (left) and Martin Rangel show their work on the board.

Getting students on board with this different approach takes about a month, and it isn’t always pretty. “I imagine it’s like parenting,” says Ms. Zunkiewicz. “My students complain, but what am I going to do, just give in? I know this is what’s best for them. It’s worth it.”

There’s that expectation of excellence, but with the grace you need to feel like you can ask questions.

– Ethan Noe, 17

For students like Michaela Frasier, Ms. Zunkiewicz’s student-led approach to instruction has proven both more challenging and ultimately more gratifying than previous math classes.

“I like the challenge Ms. Zunkiewicz proposes for us in her class,” Michaela says. She says she’s been pushed to “actually understand instead of just memorize, so it’s harder.” Rather than causing her frustration, though, Michaela says that the added challenge has been coupled with a classroom environment where it’s safe to ask questions.

“In other math classes, you don’t really want to say anything because you feel like you’re the oddball because you’re wrong,” she explains. “In Ms. Zunkiewicz’s math class, you’re comfortable saying, ‘I don’t understand. Can you help me?’”

Michaela Frasier says she and her classmates talk about math outside Ms. Zunkiewicz’s class, too.

Her classmate Ethan Noe, 17, concurs. “There’s that expectation of excellence, but with the grace you need to feel like you can ask questions.”

Ethan calls Ms. Zunkiewicz’s class a “positive challenge,” because of the extra level of thinking she demands of him and his classmates. “It’s like, wow, we’re actually really learning something,” Ethan says. “You feel a little bit smarter.”

For Michaela, math has become something she and her friends chat about outside class. “We get out of class and we’re talking about pre-calculus. In other classes, we just go onto the next subject.”

Ms. Zunkiewicz says Michaela particularly struggled at the start of the year—that it was hard for her to experience a teacher who would not give her the answers.

Today, Michaela’s come around. Asked what it’s like when she and her classmates work their own way through a tough concept to true mastery, Michaela doesn’t hesitate.

“It’s a sensational feeling.”

And what of her classmate Martin Rangel, now six months into the pre-calculus course he begged to get out of? “I ask a lot more questions now than I used to. In her class, I thought everything was hard at the beginning. Now I feel like I do belong. I can go beyond what I thought I could do because of this class.”

I can go beyond what I thought I could do because of this class.

– Martin Rangel, 17

Read Another Student's Story

Stay in the Know

Sign up for updates on our latest research, insights, and high-impact work.

"*" indicates required fields